“This book’s footnotes are whatever the opposite of scholarly is, many of them completely daft.”–Dwight Garner, New York Times, November 6, 2012, review of “Bruce [Springsteen],” by Peter Ames Carlin

A thought for the day

“Pinny”

Listening to Geoffrey Nunberg’s “Fresh Air” commentary about not one-off Britishisms, I was struck by this: ” … when [the British] do send us an occasional blockbuster like Harry Potter, they’re considerate enough to Americanize ‘dustbin’ to ‘trash can’ and ‘pinny’ to ‘apron.'”

The reason I was struck is that, about fifteen years ago, shortly after we moved to a town in suburban Philadelphia, my older daughter, Elizabeth Yagoda, started to play soccer. When her team practiced, the girls on one side would put loose mesh jerseys–all of the same color–over their shirts. These were referred to as pinnies. Or at least that’s what I thought they were referred to as; the other possibility was some Southern-derived pronunciation of pennies. I had never heard the term before.

The mystery has persisted, till Nunberg’s comment inspired me to investigate. The OED’s definition of pinny is “A pinafore; an apron, esp. one with a bib.” The dictionary cites a 1939 Angela Thirkell novel: “If we had known mummie was coming, we’d have had our clean pinny on.”

Current British usage uniformly favors the apron meaning, as in this 2010 quote from The People about the Beckham family: “I can reveal Posh, 36, will be putting her pinny on to cook for the couple’s parents including Dave’s dad Ted, who has previously been shunned from the family’s festivities.” That meaning has not penetrated the U.S.

And what about the athletic usage? Wikipedia is of some help:

In modern times, the term “pinny” or “pinnie” has taken another meaning in sports wear, namely a double-sided short apron, often made of mesh, used to differentiate teams. This usage is chiefly British, with some usage in Canada and the United States. This type of pinny is also known as a scrimmage vest.[citation needed]

Citation needed indeed. I haven’t been able to find any British use–and would appreciate any reader input–but pinny appears to have been used to denote “scrimmage jersey” in the U.S. by the early 1950s. Renata Adler (born: 1938) writes in her 1976 novel, Speedboat, “It is all gone, after childhood knowledge of myths, constellations, baseball scores, dinosaurs, and idioms of the tennis court and athletic field. There are outcroppings of the old vocabularies still. Pinnies from field hockey. Heels down. Bad hop. Sorry. My fault. So sorry.”

And there is this in a 1951 publication called “Developing Democratic Human Relations” (the passage is apparently a list of guidelines for scholastic sports): “7. Short cuts to efficient organization for intramural programs (developed through the democratic process): a. Schedule for field and courts with the games schedule. b. Previous knowledge of pinny or shirt teams and direction of goal or basket…”

Today, the word is out there in America, but not completely familiar, as evidenced by way the singular is sometimes spelled pinny and sometimes pinnie, by the quotation marks in this 2012 New York Times blog post–“Children trade or alter clothing; they wear it in situations for which it wasn’t intended (a sports bra under a “pinnie”: perfect for lacrosse, less so in the classroom)”–and by the definition provided in this one, about a pickup soccer game:

“Sides of six to nine are assembled from players serendipitously wearing like-colored tops; noncoordinated participants, mostly men but some women, team up and wear borrowed practice pinnies (mesh vests).”

Almost precisely a year ago, ahead of the Harvard-Yale (American) football match–known in those parts as The Game–the Yale Daily News published this item:

In a clear demonstration that Harvard students measure their “superiority” by their university’s single-digit acceptance rate and their pinnies, a group of Harvard entrepreneurs have launched an “#OccupyYale” pinny — prominently displaying the school’s 6.2% admissions rate — for Cantabs to wear at The Game this weekend.

Nunberg on NOOBS

Linguist Geoffrey Nunberg weighed in on NOOBs a couple of days ago on the public radio program “Fresh Air,” graciously crediting this blog. He had a nice metaphor for the whole phenomenon: “Adding a foreign word to your vocabulary is like adding foreign attire to your wardrobe. Sometimes you do it because it’s practical and sometimes just because you think it looks cool.”

He named one off as a useful addition to the American lexicon, and dab hand, spot on and gobsmacked as having “a whimsical appeal.”

One the other hand, he went on:

…other words are imported just for effect. “I’m not very keen on it, but I’ll have a go.” People claim to discern some useful nuances of meaning there, but who are they kidding? It’s like explaining that you bought that $800 Burberry plaid tote bag because it gives you a better grade of vinyl.

And Nunberg had a good innings on the difference between Not One-Off Britishisms in the U.S. and Not One-Off Americans in the U.K.:

Actually, the British are the ones who have conniptions over foreign words. Whenever the British media run a piece on Americanisms, it gets hundreds or thousands of comments, most of them keening indignantly over the American corruption of English: “I cringe whenever I hear someone say ‘touch base.’ ” “Faucet instead of tap??? Arrrrrrrghhh!”

That might seem a little over the top for a race that’s not known for its demonstrativeness. But the Brits have had to endure an inundation of American popular culture that has saturated every corner of their vocabulary with Americanisms — probably including the word “Brits” itself….

We react very differently to Britishisms. To the British, our words “wrench” and “sweater” are abominations; to us, their words “spanner” and “jumper” are merely quaint. To Americans, after all, Britain is just a big linguistic theme park. The relative handful of Britishisms that do find their way here may raise some eyebrows, but they’re hardly a threat to American culture. After all, British English comes to us through a much narrower pipe than the one that floods Britain with our words. They pick up our language from Friends and The Avengers. We pick up theirs from Downton Abbey and Inspector Morse. And when they do send us an occasional blockbuster like Harry Potter, they’re considerate enough to Americanize “dustbin” to “trash can” and “pinny” to “apron.”

No doubt some of the newcomers will wind up as naturalized American citizens. After all, “tiresome” and “fed up” were considered affected Britishisms when they made their American debut in the 19th century. My guess is that “spot on” is already on the way to becoming everyday American. But it will be awhile yet before it reaches the cultural outer boroughs.

Plenty of food for thought there. As for me, I’m planning to have a go at have a go.

“Gap year”

There was some grumbling after gap year–meaning a year taken off between high school and college–made a good showing in the recent poll asking readers to vote on potential new NOOBs. Not really a Britishism, some said. We Americans were saying it back in the 70s, one person claimed.

I don’t think so.

It’s certainly the case that gap year is common in the U.S. now. My own kids and their friends tossed around the phrase when they were at that age a half-dozen years ago. The New York Times observed a couple of months ago, “The idea of a gap year between high school and college could be tempting to students who are not ready to transition to the next level of education.” There is an organization called USA Gap Year Fairs that hooks students up with gap year providers. Moreover, I have no doubt that U.S. students were taking a year off before college in the 70s.

But they weren’t calling it a gap year. That is a Britishism, without a doubt. The OED’s first citation is from The Times (the one in London) in December 1985: “Many young people are making deliberate decisions to take a year off, often referred to as the gap year.” The wording suggests the phrase had been relatively recently coined. The use of the word gap in this context may have been a contribution of a British organization called Latitude Global Volunteering whose website states that it was founded forty years ago under the name Gap Activity Projects.

The first U.S. use of the phrase on the Lexis-Nexis database comes from a 1996 Atlanta Journal Constitution article that leaves no

doubt as to the phrase’s newness in the U.S. or its national origin: “… taking a break before or during college can be beneficial, according to a new book, ‘Taking Time Off’… It’s a practice common in other countries. For example, in England many college-bound students take a “gap year” for travel before beginning their studies.”

The New York Times’ first reference came in 2000 and has the same vibe: “Students taking a year off prior to Harvard are doing what students from the U.K. do with their so-called ‘gap year.'”

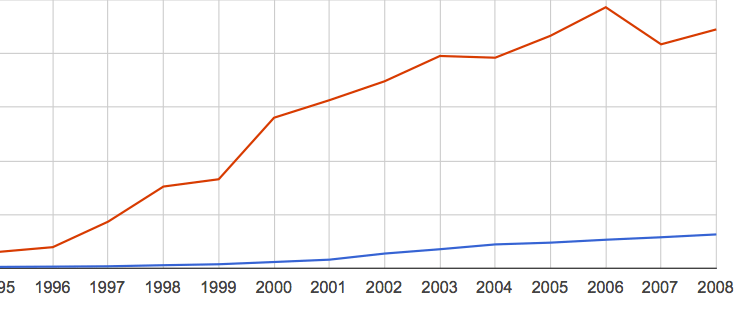

Final proof comes via Google’s Ngram Viewer, which, in an exciting development, now allows comparison of U.S. and British use of a word or phrase on the same chart! The Ngram below shows compares use of gap year in Britain (red) and the U.S. (blue) between 1995 and 2008:

Seen on the newsstand

Not really. This was the payoff of a Conan O’Brien bit where he lamented the demise of Newsweek and showed some magazines that have weirdly outlasted it, including “Pond Hoppin” (a cover lines notes that the periodical is “Brought to you by BASSIN’ and Crappie World”) and “Where to Retire.” He then brought in some fake mags, including the above compendium of ginger news. The fingers in the photo are Conan’s.

“Aggro”

Via Twitter, @I_Am_Maylin_Now suggested that I look at aggro, and when I said it was a term with which I was not familiar, he directed me to a World of Warcraft (WoW) wiki site with this definition:

Aggro is a jargon word in WoW, probably originally derived from the English words “aggravation” or “aggression”, and used since at least the 1960s in British slang. In MMORPGs [Massively multiplayer online role-playing games], such as WoW, aggro denotes the aggressive interests of a monster/NPC. Some examples are “We’ve got aggro!” and “Go aggro that monster”.

The OED bears out this out (regarding the origin), citing a 1969 article in It magazine (“At the moment kids are split up into different subcultural groups which have been driven by the system into a permanent state of aggro with each other”) and Martin Amis’s 1973 novel The Rachel Papers: “It wasn’t day-to-day aggro, nor the drooped, guilty, somehow sexless disgruntlement I had seen overtake many relationship.”

The dictionary doesn’t recognize aggro as a verb, but does locate an adjectival use in Australia, as in “My New York paintings were all pretty aggro, with plenty of black” (Sunday Mail of Brisbane, 1985).

As my Twitter friend might have predicted, the term seems to have entered the U.S. through the world of gaming, with the OED citing Wired magazine in 1999: “A gaming device that brings skiing, snowboarding, and skateboarding into your house without thrashing the furniture… The 2-foot X Board lets vid kids stand and deliver aggro drops, extreme spins, and more.” But it’s spread out since then, with Time Out New York asking in 2008, “Are bike enthusiasts too aggro in defending their rights to NYC’s thoroughfares?” and Vanity Fair referring last year to “steroids, which bulk the muscles and ramp up the aggro.”

The honour! The honour!

NOOBs reach the White House

“… there are people in Iran who have the same aspirations as people all around the world, for a better life. And we hope that their leadership takes the right decision.”–Barack Obama, third presidential debate, October 22, 2012. (Thanks to Gigi Simeone)

Speaking of “skint”

Skint didn’t get much love in the NOOB readers’ poll, but legendary Baltimore Sun copyeditor (aka subeditor) John McIntyre is a fan: