On Facebook, the writer Sonia Jaffe Robbins posted this quote from a New York Times article about the new mayor of New York, Zohran Mamdani.

With any new administration comes a roster of ascendant power players unaccustomed to high influence. Mr. Mamdani’s New York has elevated beanie-wearing socialists, aspiring rent-freezers, backbench lefty legislators who knew Mr. Mamdani, until quite recently, as a backbench lefty legislator.

Sonia wondered: “What exactly is a ‘beanie-wearing socialist’? What socialists wear beanies? What kind of beanie?” (A commenter had another question: “What is a backbench?”)

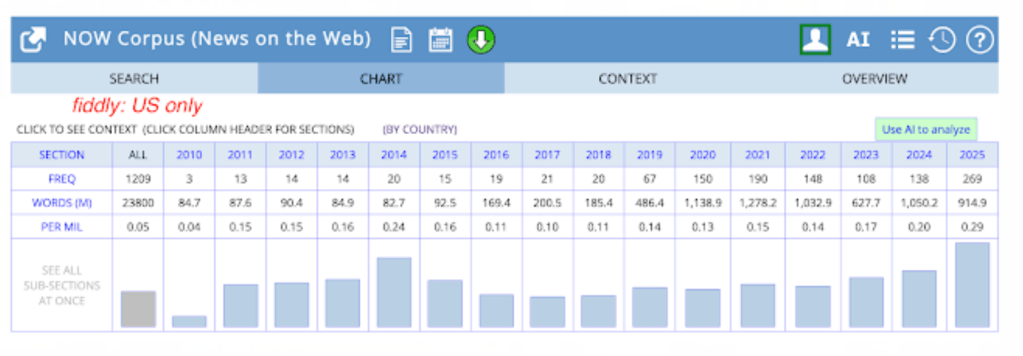

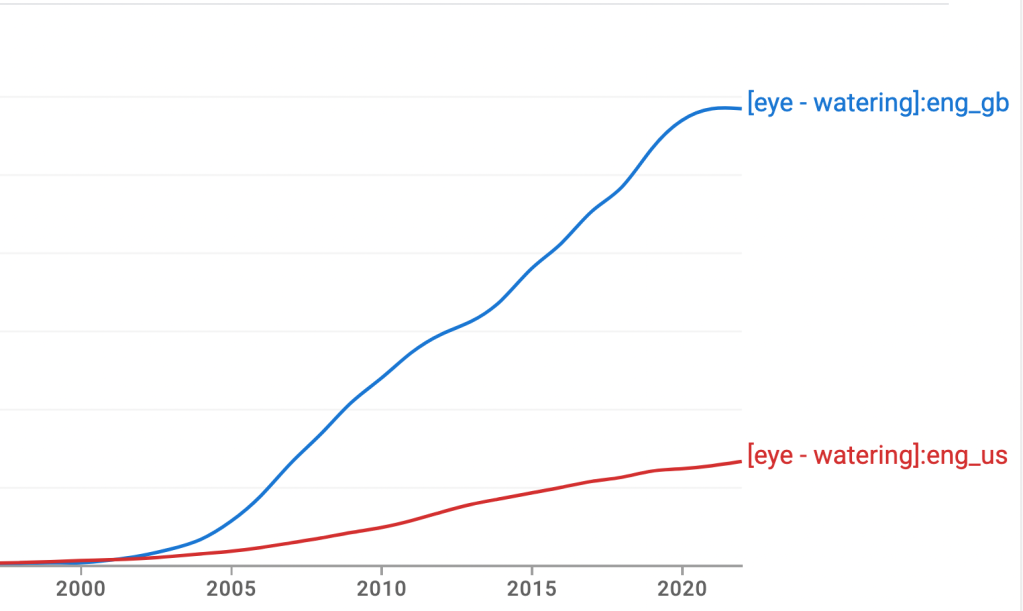

Someone replied, “Knit caps, I think,” and I responded to her: “Right, something like 10-15 years ago they started to be called beanies, who knows why.”

Not only was my timing off by a good decade, but, to my chagrin, I missed the British/Australian connection.

My first stop in looking into the usage was the OED, but my second, Green’s Dictionary of Slang, did a more comprehensive job with “beanie.” Its definition is: “(orig. US) orig. a small, tight-fitting cap, similar to a large skull-cap; thus propeller-beanie, such a cap with a small propeller affixed to its top; also used for any shape of hat.” The first quote is from the cartoonist and slang pioneer T.A. Dorgan (TAD) in 1904, the second is form the Mutt and Jeff comic strip six years later (“I’ll go right over and get a felt beanie”), and the third, from an Arizona newspaper in 1921, is, “Each year the freshmen wear their beanies until the first of April.”

Subsequently, a strong connection developed between beanies and U.S. colleges. Wikpedia reports that beanies “were worn by college freshmen and various fraternity initiates as a form of mild hazing. For example, Lehigh University required freshmen to wear beanies, or “dinks”, and other colleges including Franklin & Marshall, Gettysburg, Rutgers, Westminster College, and others may have had similar practices….At Cornell University, freshman beanies (known as “dinks”) were worn into the early 1960s.”

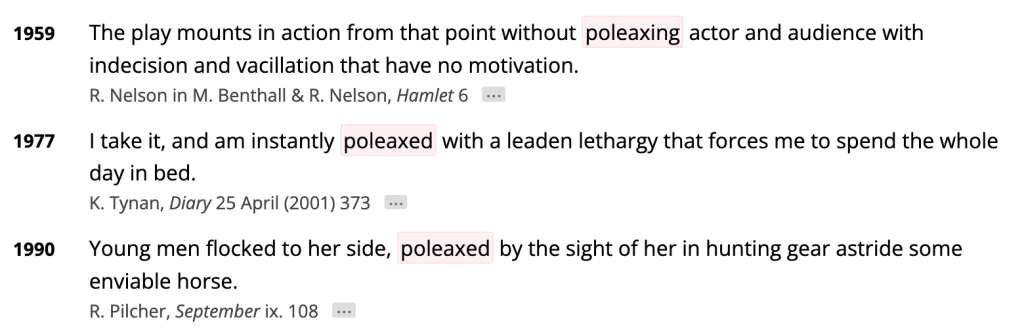

Meanwhile, the propeller thing happened. I direct anyone interested to the comprehensive history Ian Ellis published in the Today in Science website, but for now, here’s Ellis on the origin:

“It is generally accepted to have been first improvised in Cadillac, Michigan, using a beanie (a visorless cap) in 1947, made by Ray Faraday Nelson. It quickly became an icon for science fiction fans to identify themselves, and a national fad.

“In a published interview1, Nelson described how ‘In the summer of 1947, I was holding a regional science fiction convention in my front room and it culminated with myself and some Michigan fans dressing up in some improvised costumes to take joke photographs, simulating the covers of science fiction magazines. The headgear which I designed for the space hero was the first propeller beanie. It was made out of pieces of plastic, bit of coat-hanger wire, some beads, a propeller from a model airplane, and staples to hold it together.'”

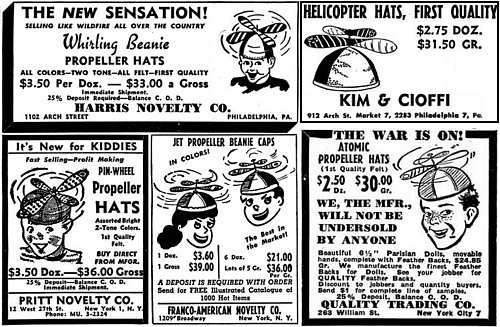

And for some unlikely reason, the propeller beanie became a fad, as witness these ads from Billboard magazine in 1948:

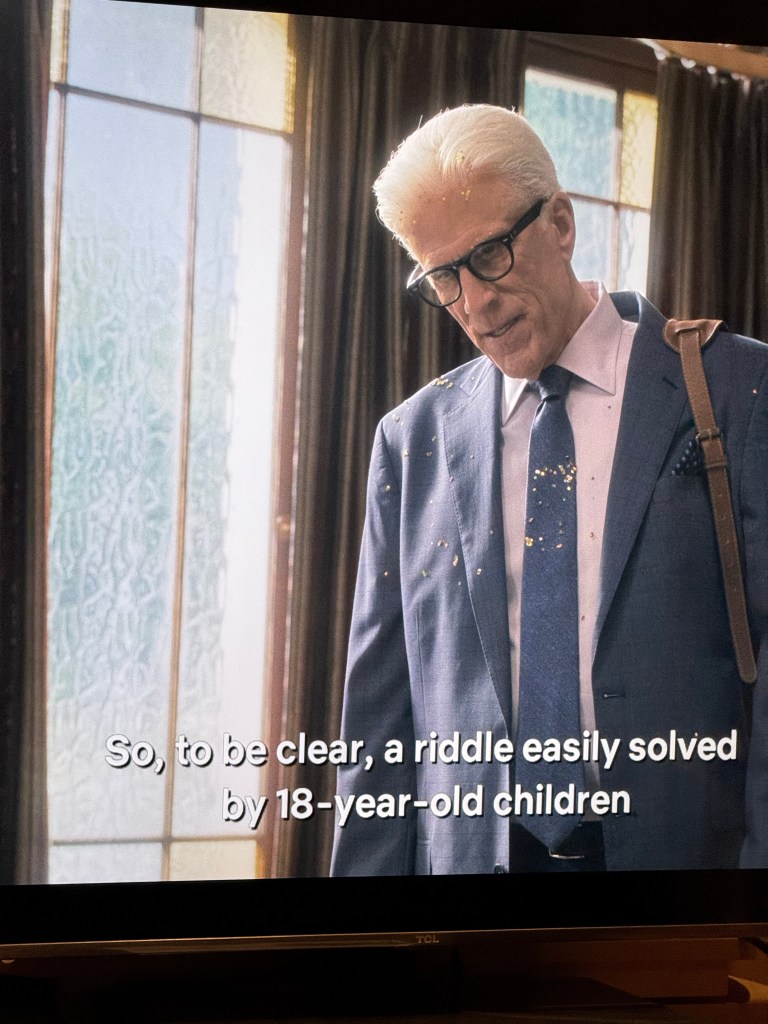

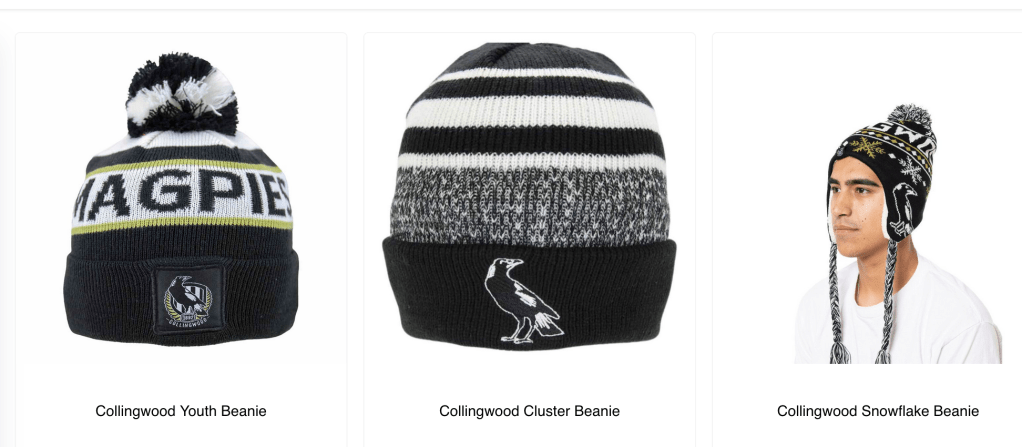

As for beanies as knit hats–also known as watch caps or toques–the terminology seems to have started in Australia, where they were worn by surf lifesavers. I’m guessing that’s the sort of beanie referred to in a 1986 Australian book quoted by Green’s: “He had on an old pair of overalls and a beanie.” But the connection is definite in this line from an Australian book published ten years later Peter Temple’s Bad Debts: “The beanie, for Christ’s sakes. It’s Collingwood beanie.” Collingwood is an Australian Rules Football club, and here are some of their beanies:

(I’ll add that I first became aware of this meaning for beanie when I was gifted one a few years ago by my study-abroad host at University College, Melbourne, Tim McBain.)

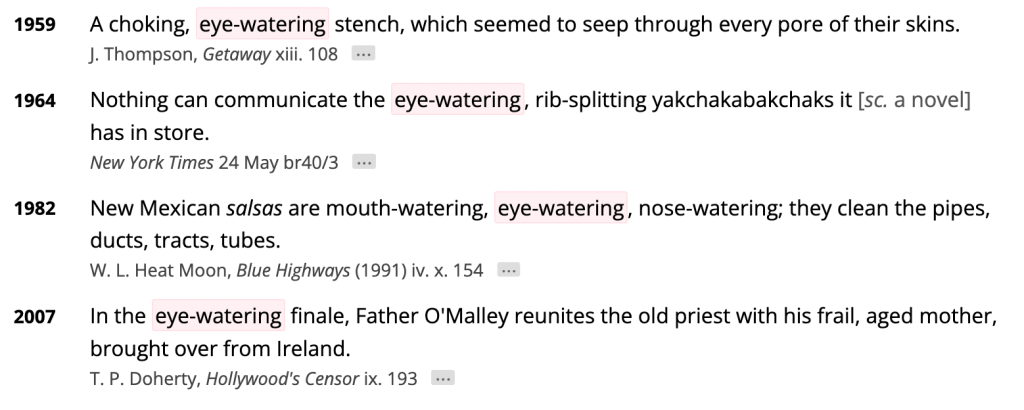

The sense had arrived in the U.K. by 2000, per this Green’s quote from The Independent on Sunday: “Roll the beanie over your head until it’s full stretch below your ears.”

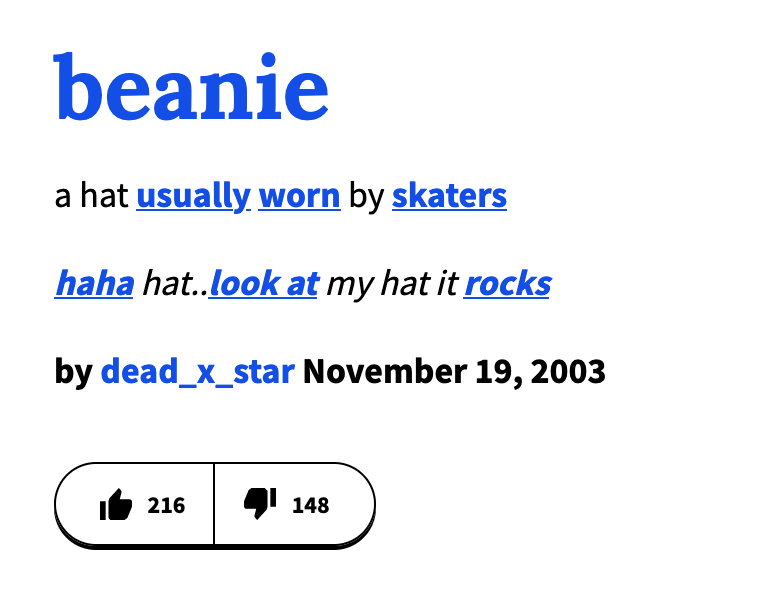

U.S. adoption came no later than 2003, when this definition was posted on Urban Dictionary:

Since then, in addition to skaters, beanies have been associated with grunge rockers, slackers, hipsters, and now, apparently, socialists.