In the very early days of this blog, I did a post on “erm,” which I took and still take to be the British version of the American “um,” with similar pronunciation. (That is, the “r” is silent, though on some occasions in the U.K. it’s pronounced more like “em.”) At that time, there was no entry for “erm” in the OED, so I constructed my own definition: “Interjection. Self-conscious vocalism, indicating skepticism.” The idea being that people said “erm” or “um” when they were hesitating, and that writers employed in attempting to cleverly call attention to what follows in the sentence. American speakers and writers had been doing the same thing with “um” but in the post I gave two recent U.S. “erm”s.

- “Here’s a report on the, erm, incident from CBC’s nightly national newscast.” (Slap Shot blog, New York Times, November 29, 2007)

- ”Justice Breyer asks a hypothetical question that he will pose several times today: ‘Imagine a well-educated American woman marries a man from a foreign country X. They have a divorce. The judge says the man is completely at fault here, a real rotter. The woman is 100 percent entitled to every possible bit of custody and the man can see the child twice a year on Christmas Day at 4:00 in the morning.’ (Erm. Isn’t that once a year?)” (Dahlia Lithwick, Slate, January 10, 2010)

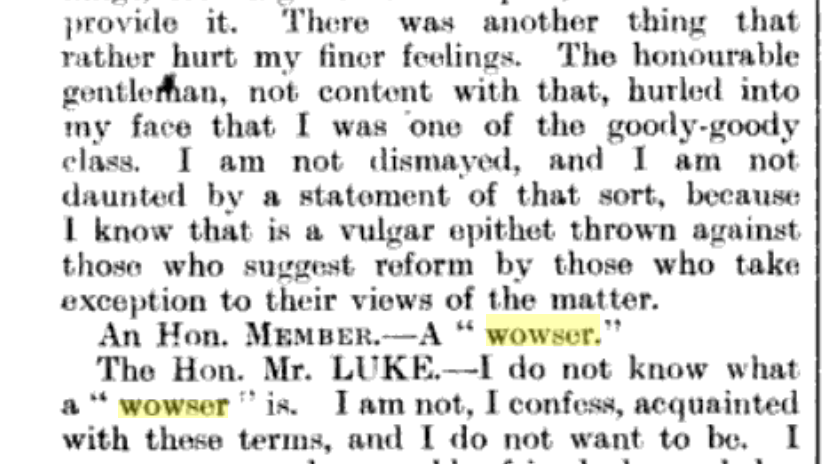

In March 2023, the OED published an “erm” entry, with this definition: “Used to express uncertainty, embarrassment, a pause to consider one’s next words, etc., or as a conversational filler expressing hesitation or inarticulacy.” Interestingly, the citations, which ranged from 1911 to 2017, had no jokey written uses of “erm,” only lines of dialogue from works of fiction, or journalistic quotes, including this from The Dalesman in 2017: “The new vicar is visiting members of his Wensleydale parish. ‘Erm, could I just ask why you have a bucket of manure in your front room?’ asks the flustered man of the cloth.”

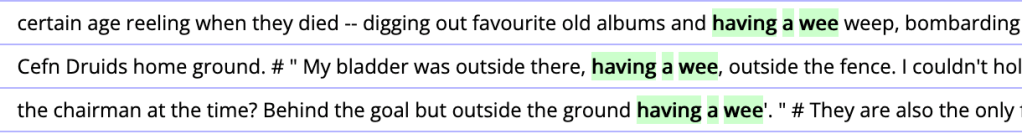

I had occasion to look this up because over the course of the week, I encountered two U.S. examples. The first was in the New York Times crossword puzzle:

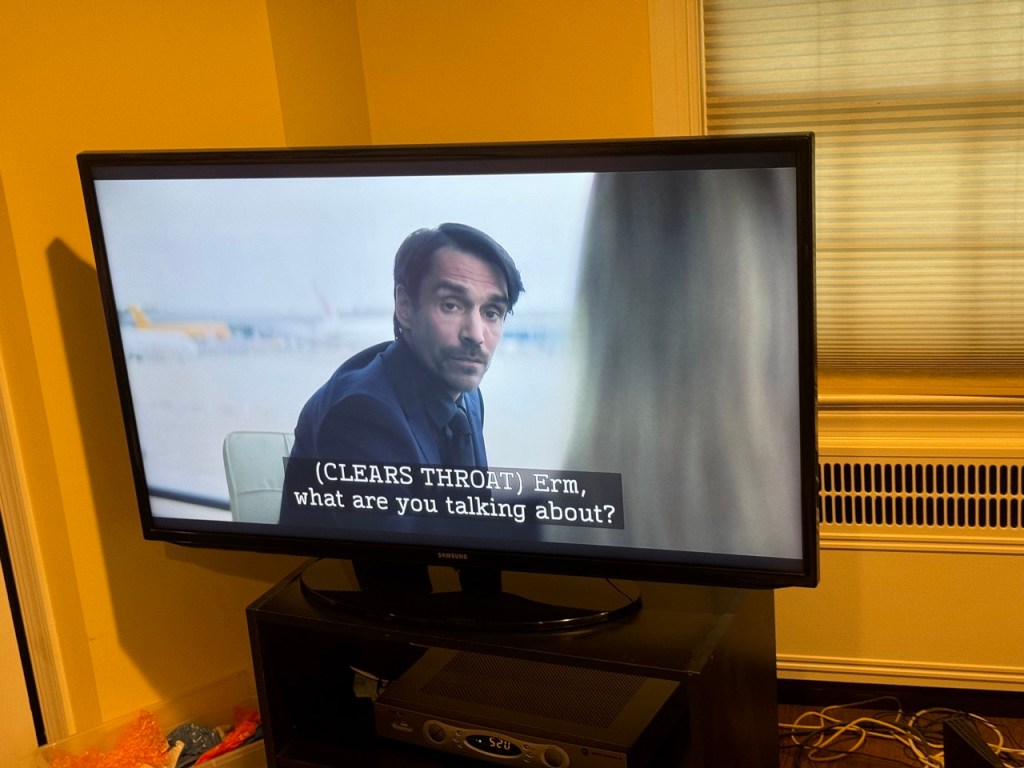

And the second was in the captioning to the FX television series The Veil. (The character speaking isn’t British.)

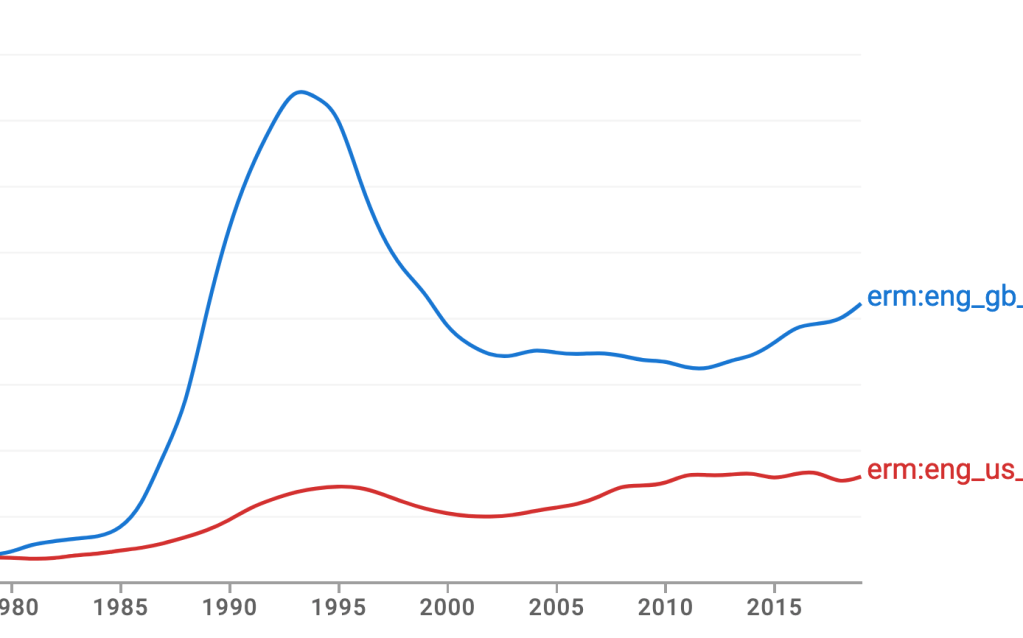

Here’s what Google Books Ngram Viewer has to say about the use of the word in written sources in Britain and America:

Supporting the idea of a mild uptick in the U.S. is that fact that it’s been used four times in the past year in the New York Times, including:

- “… obsessing over who Donald Trump will pick as his new pain sponge — erm, running mate …”–Opinion columnist Michelle Cottle

- “Every generation, it seems, has a way of ‘discovering’ items of dress that previous generations dismissed in triumph, recontextualizing them and claiming them for its own, like anthropologists unearthing buried treasures. Wide ties? Bell bottoms? So ironically cool! Corsets? Neato! Waistcoats? Funky. Spats? Erm … maybe for a costume party.”–Fashion writer Vanessa Friedman

Such American uses are both cutesy and needlessly British, seeing as we’ve got our homegown “um.” So, erm, maybe give “erm” a rest?