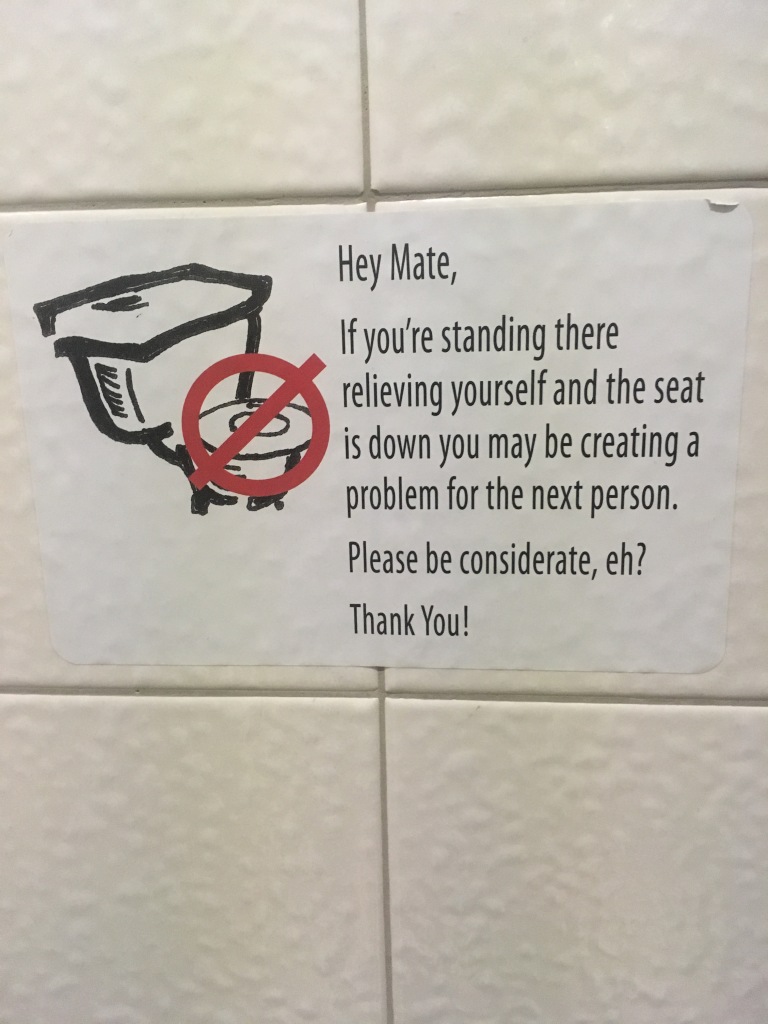

In my Brooklyn wanderings the other week, I came upon this sign outside a bar:

I had encountered “schooner” as a portion size for beer in my recent Australia visit, but didn’t have a clear sense of what it meant, other than larger than the smallest size (called “pot,” as I recalled). And by the way, if you’re not from here, “Bud” is Budweiser, probably the most famous American beer.

I checked the OED, which told an interesting, somewhat complicated story. It gives a United State origin for “schooner” as a beer vessel, citing a definition in an 1879 edition of Webster’s dictionary: “A tall glass, used for lager-beer and ale, and containing about double the quantity of an ordinary tumbler.” An 1896 quote from a Scottish newspaper shows the term had crossed the Atlantic, and specifies its size: “‘the schooner’ [contains] 14 fluid ounces, or 2 4-5ths imperial gills … [and is] found in everyday use, under various names, in London, Glasgow, Aberdeen, and elsewhere.”

But then, the term seems to have subsided both in Britain and the U.S., only to reappear, by the 1930s, in Australia and New Zealand. A fascinating 2011 article in Australia Beer News traced the tangled history of “schooner” in New South Wales. The author, Dr. Brett J. Stubbs, limits himself to that state because “tracing the history of the schooner glass (let alone of beer glasses in general) in Australia requires more than just a short article.” To summarize his tale would require more than just a short blog post, but fortunately, this graphic is floating around the internet (apologies for not being able to figure out and cite the original source). It brings to mind the apocryphal factoid about Eskimos having 100 or some other large number words for snow.

Meanwhile, by the 1960s the meaning of “schooner” in Britain had changed to, as the OED puts it, “A tall, waisted sherry glass” holding 3.5 ounces. The writer of a 1973 article in The Times wasn’t happy with this development, referring to “the abominably proportioned waisted Elgin glass, sometimes used for sherry, or its vulgar outsize version, the schooner.”

And what of North America? Not surprisingly, we have super-sized the schooner. The OED is no help here, but this is what Wikipedia has to say:

In Canada, a “schooner” refers to a large capacity beer glass. Unlike the Australian schooner, which is smaller than a pint, a Canadian schooner is always larger. Although not standardized, the most common size of schooner served in Canadian bars is 946 ml (32 US fl oz); the volume of two US pints. It is usually a tankard (mug) shaped glass, rather than a pint-shaped glass….

In the United States, “schooner” refers to the shape of the glass (rounded with a short stem), rather than the capacity. It can range from 18 to 32 US fl oz (532 to 946 ml).

Sure enough, here’s an article from a Lawrence, Kansas, newspaper about a bar in that college town that serves 32 oz. schooners in the rounded shape — though “If the bar runs out of clean glasses on a busy night, you’ll get your 32 ounces of beer in a giant plastic cup.”

In my preliminary research on the topic, I posted on Facebook the Brooklyn sign and a query as to the meaning of “schooner.” Someone replied that in New England, it’s 10 ounces — perhaps an example of a British usage that has been retained in that region, like “rubbish.” But my favorite comment came from my friend Jan Ambrose, who is discriminating in her beer tastes: “There is no amount of Bud I would pay $3 for.”