Pick up or gather person(s) or thing(s); commonly used in reference to children and tickets.

“Ms. Knox, 24, from Seattle, was returned to prison to collect her possessions and left less than a few hours later.” (New York Times, October 3, 2011)

Pick up or gather person(s) or thing(s); commonly used in reference to children and tickets.

“Ms. Knox, 24, from Seattle, was returned to prison to collect her possessions and left less than a few hours later.” (New York Times, October 3, 2011)

When I recently wrote a post about mad and nutter I considered including one additional Britishism indicating insanity. I ultimately decided not to because the chance of any American using seemed closer to slim than none.

I did not count on the New Yorker. Reading the August 1 issue of that publication this morning, I came upon this sentence from Sasha Frere-Jones: “My Morning Jacket, on the recently released album ‘Circuital,’ its sixth, makes it clear that the real hippie is neither biddable nor daft.”

Thank you very much, indeed (TYVMI) has long been a go-to phrase for British interviewers and interviewees. How long? Well, it has been afoot at least since 1973, when Anthony Burgess made this amusing observation in the New York Times:

British gabbiness is also to be associated with a kind of obliquity or indirectness, which is meant to be polite, though sometimes it can be as cold as silence. Thus, an American says, “Have you change for a ten?” but an Englishman will say, “I’m really most terribly sorry to bother you, but I don’t suppose by any chance you might have such a thing as change for a pound, would you—the old quid, you know? Oh, you would? I’m really most terribly grateful. Thank you, you’re an angel. Thank you very much indeed.”

Fifteen years later, Times TV critic John O’Connor wrote this about David Frost’s substitute hosting duties on the “Today” show:

Mr. Frost is more of a bon vivant (than Jane Pauley), never at a loss for an amusing anecdote and, even through a certain early-morning bleariness, always maintaining a remarkable enthusiasm. ”Wonderful stuff!” or ”Thank you very much, indeed,” says Mr. Frost at regular intervals.

For some time, I have been waiting for TYVMI to emerge from a pair of American lips. I believe I have heard a couple of NPR hosts say it, but I didn’t take notes so can’t be sure. Christine Amanour of CNN and ABC and Stuart Varney of Fox say it all the time, but they are Brits. I will stay on the lookout, but for now have to content myself with one American sighting. It was uttered in May of this year by Paul Schott Stevens, a native of New Orleans and president Investment Company Institute, at the close of a conversation with Alan Simpson and Erskine Bowles. If by any chance you want to hear it for yourself, be my guest.

For some reason, adjectives indicating mental instability have always been a key marker of difference between American and British English. We have crazy and insane; they have mad and daft. Does the New York Times article above indicate a meeting of the minds on mad, or merely that headline writers really like short words? Only time will tell.

Moving on to nouns, I’ve always felt the U.K. nutter is more expressive than our nut, and in recent years have wondered what U.K. visitors to Philadelphia (near which I live) think when they discover that it’s governed by a Mayor Nutter. Predictably, I enjoyed this quote from a recent Reuters article on the Murdoch scandals:

“We used to talk to career criminals all the time. They were our sources,” says another former reporter from the paper who also worked for Murdoch’s daily tabloid, the Sun. “It was a macho thing: ‘My contact is scummier than your contact.’ It was a case of: ‘Mine’s a murderer!’ On the plus side, we always had a resident pet nutter around in case anything went wrong.”

My pulse quickened some months ago when the PBS program “Frontline” posted Wikileaks leaker Bradley Manning’s Facebook status updates, including this from September 4, 2009: “Thinks Cambridge, Massachusetts is full of crazy (but fun) nutters.” But it turns out that Manning’s mother is from Wales and he spent much of his adolescence in that country.

However, I haven’t given up hope on the nutter front and was very pleased to read this yesterday in John Nichols’ blog at The Nation:

But it is becoming all too clear that the “right-wing nutter” fantasy that the debt-ceiling debate could be gamed for political points is crashing into the prospect of a “crunching global recession.”

So far, no sightings of daft.

The Boston Globe has an amusing piece today about the different American and British meanings for pants: “trousers” here and “underpants” there. No sign yet of the Britishism getting any traction in these parts. If that does ever happen, it will kick the venerable expression “keep your pants on” up a few notches.

As I realized when I first looked at London tube maps, in British English, journey basically means trip. In American English, the word is almost always used either metaphorically or to refer to a really long and momentous trip–journey though life, journey into terror, journey to the center of the earth, etc.

Are we starting to adopt the British use? Well, maybe. Megabus–a Canadian-owned company, admittedly–is big on journey. (They also ask for the expiry, rather than expiration, date on your credit card.) And an item in the June 3 Hattiesburg (Mississippi) American notes, “TripIt is one of many apps that helps you organize your journey.” (Possibly the writer was using elegant variation to try to avoid repeating trip.)

Meanwhile, perhaps British use is changing as well. I note that the new Steve Coogan film about a journey (literal and figurative) he takes with his buddy is called “The Trip.” Stay tuned.

One of my Facebook friends posted this, or should I say one of me Facebook mates. Click the graphic to see the whole thing.

Puts me in mind that I’ve noticed my (college-age) children facetiously using me=my. Possibly they are taking it from Popeye rather than working-class Britain. In any event it is now officially on the radar.

Coined through onomatopoeic metonymy (approximating the sound telephones used to make), and appeared surprisingly soon after the phone’s invention. First use in the OED is from Punch in 1880: “For you upon them both may frown, And say that you are shocked, or May knock the Secretary down, And then ring up the Doctor.”

Coined through onomatopoeic metonymy (approximating the sound telephones used to make), and appeared surprisingly soon after the phone’s invention. First use in the OED is from Punch in 1880: “For you upon them both may frown, And say that you are shocked, or May knock the Secretary down, And then ring up the Doctor.”

That is a verb form, meaning “to place a phone call to”; American equivalents are call, call up, or phone. The noun form give (someone) a ring appears roughly the same time.

Google Ngram shows interesting patterns in the various forms in British and American English. For one thing, the phrase give me a ring has historically been about equally popular in Britain and the U.S. Currently, following a three-decade upswing, it shows significantly more frequent use here. We also will frequently say something like, “I answered on the fourth ring”–notwithstanding, of course, that telephones don’t make ring-like sounds anymore. And who can forget Ernestine’s “One ringy dingy, two ringy dingies…”?

Verb forms are still more frequent in the U.K. although, typically for a NOOB, U.S. use has spiked since 1990.

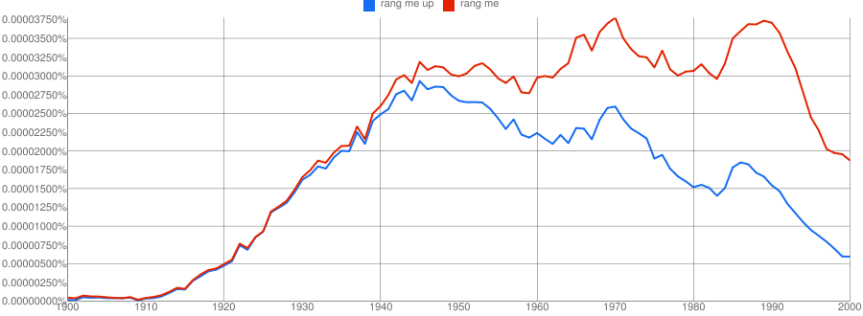

The British verb use is more complicated and interesting. The chart below shows British usage of “ring me up” (blue) and “ring me” (red) between 1900 and 2008. Up until about 1940, hardly said merely “ring me”–the phrase had to be “ring me up.” (The OED’s first cite for the up-less ring is 1930) The short form achieved equal popularity around 1980, and currently is used about twice as often. My hypothesis is that ring up sounds to British ears like a stage caricature of the way they talk, so they are in the process of rejecting it–kind of like “telly” or “I say, old boy.”

A (n American) person I follow on Twitter–no names–just used “by-election” to refer to the recent Congressional race in upstate New York.

My work here is done.

A reader who goes by dw alerted me to this classic New York Post headline:

I have given a lot of thought to wanker, always deciding that it had not really gotten sufficient traction in the U.S. to be a full-fledged entry in this blog. I still think that’s the case, but maybe the Post–which is, of course, an Aussie production–will prove to be the tipping point.