There was some grumbling after gap year–meaning a year taken off between high school and college–made a good showing in the recent poll asking readers to vote on potential new NOOBs. Not really a Britishism, some said. We Americans were saying it back in the 70s, one person claimed.

I don’t think so.

It’s certainly the case that gap year is common in the U.S. now. My own kids and their friends tossed around the phrase when they were at that age a half-dozen years ago. The New York Times observed a couple of months ago, “The idea of a gap year between high school and college could be tempting to students who are not ready to transition to the next level of education.” There is an organization called USA Gap Year Fairs that hooks students up with gap year providers. Moreover, I have no doubt that U.S. students were taking a year off before college in the 70s.

But they weren’t calling it a gap year. That is a Britishism, without a doubt. The OED’s first citation is from The Times (the one in London) in December 1985: “Many young people are making deliberate decisions to take a year off, often referred to as the gap year.” The wording suggests the phrase had been relatively recently coined. The use of the word gap in this context may have been a contribution of a British organization called Latitude Global Volunteering whose website states that it was founded forty years ago under the name Gap Activity Projects.

The first U.S. use of the phrase on the Lexis-Nexis database comes from a 1996 Atlanta Journal Constitution article that leaves no

doubt as to the phrase’s newness in the U.S. or its national origin: “… taking a break before or during college can be beneficial, according to a new book, ‘Taking Time Off’… It’s a practice common in other countries. For example, in England many college-bound students take a “gap year” for travel before beginning their studies.”

The New York Times’ first reference came in 2000 and has the same vibe: “Students taking a year off prior to Harvard are doing what students from the U.K. do with their so-called ‘gap year.'”

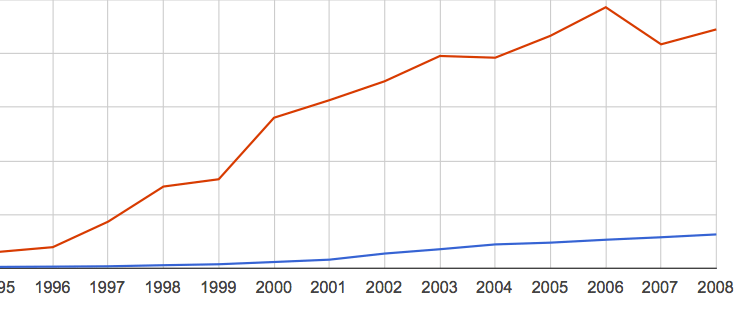

Final proof comes via Google’s Ngram Viewer, which, in an exciting development, now allows comparison of U.S. and British use of a word or phrase on the same chart! The Ngram below shows compares use of gap year in Britain (red) and the U.S. (blue) between 1995 and 2008: