Hold your fire! I know that the spelling “advisor” is not British. However, people think it’s British (someone even said that exact thing at a faculty meeting last week, unprompted by me), so I present the post below. (It originally appeared in the Chronicle of Higher Education’s Lingua Franca blog.) And I have devised for it a new category, “Faux NOOBs.” Additional nominations welcome.

Quick quiz: What do you call a person whose job is to offer advice? Or, rather, how do you spell that job?

If you said advisor, you would be in accordance with 100 percent of my students; with the practice of my university and I believe most others in this country; with the popular Web site TripAdvisor; with Merrill Lynch, which sends to its customers a publication called Merrill Lynch Advisor; and, in fact, with the English-speaking world generally.

If you answered adviser, you would be right. Or, to be more precise, right from the perspective of The New York Times, the Associated Press, The Chronicle of Higher Education, and history. Adviser first appeared in 1611, according to the Oxford English Dictionary. It was formed by appending the suffix –er (in this case, merely the letter r) to the verb advise, along the lines of such similar constructions as baker, candlestick-maker and, well, not butcher, which comes from the Old French bouchier, but teacher, seeker, and beekeeper.

The OED’s first citation of a different spelling is a periodical that first came out in 1899 and was called, simply, Advisor. The dictionary doesn’t specify its country of origin, but the new spelling became sufficiently popular in the United States that American Speech, the journal of the American Dialect Society, mocked it in 1931: “Following the advent and acceptance in this country of advisors, newspapers now occasionally mention debators.” (There are, of course, -or nouns for occupations and identifications, but they are usually not formed from verbs: doctor, debtor, proctor, author, executor, curator, donor.)

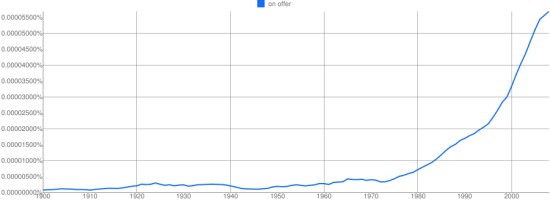

The chart below is a Google Ngram showing the comparative frequency, in books published in America between 1900 and 2008, of adviser (blue line) and advisor (red line). The -or spelling pulls ahead in about 1999. (In Britain, -er is still ahead though its lead is fading.)

Ngram’s database, as I say, consists of books, which tend to stick with traditional usages longer than other forms of writing do. The Internet itself gives a more accurate snapshot of current usage, and if you stage a Google Fight between the two spellings, -or blows -er away, by 23.7 million to 5.7 million.

How to explain the dominion of advisor? First, it sounds fancy (because, I conjecture, the real –or nouns have longer pedigrees than the formed-from-verbs -er ones). Second, it sounds British. And when it comes to language in our country, that is an unbeatable combination.

The color or colour between black and white. U.S. spelling has traditionally been gray, and British (or at least modern British) grey. The OED notes:

The color or colour between black and white. U.S. spelling has traditionally been gray, and British (or at least modern British) grey. The OED notes:

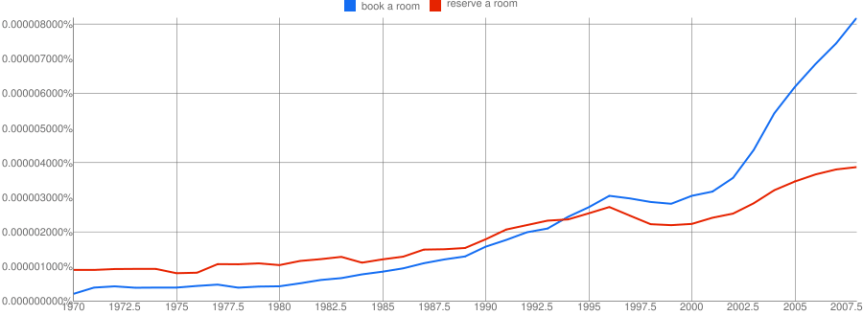

When I first spent significant time in London, about fifteen years ago, one of the first words that struck me as unusual was book–used as an all-purpose verb to indicate, well, as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it: “To engage for oneself by payment (a seat or place in a travelling conveyance or in a theatre or other place of entertainment).” The OED cites a first use in Disraeli’s 1826 novel

When I first spent significant time in London, about fifteen years ago, one of the first words that struck me as unusual was book–used as an all-purpose verb to indicate, well, as the Oxford English Dictionary puts it: “To engage for oneself by payment (a seat or place in a travelling conveyance or in a theatre or other place of entertainment).” The OED cites a first use in Disraeli’s 1826 novel