Former Florida Governor Jeb Bush’s campaign for the Republican nomination for president is ailing, badly. Before yesterday’s Iowa caucuses he could not but acknowledge that he had no chance of finishing near the top. He said of the presumed front-runner, Donald Trump, “It’s all about him and insulting his way to the presidency is the organizing principle.”

Then he said of the other leaders in the polls, Senators Ted Cruz and Marco Rubio: “The two other candidates that are likely to emerge in Iowa are two people that are backbenchers who have never done anything of consequence in their lives.”

Bush has a fondness for the term (an explanation of which you can find by following the above link), having used it in a Republican debate, after a skirmish between Rubio and Cruz: “this last back and forth between two senators–back bench senators, you know–explains why we have the mess in Washington, D.C.”

Unfortunately for Bush, his efforts to dismiss the senators not only as participants in the mess in Washington, but as junior participants, with no experience at actually running anything, doesn’t appear to have much traction. Cruz won the Iowa caucuses with 28 percent and Rubio was a strong third at 23. Bush’s showing? 2.8 percent.

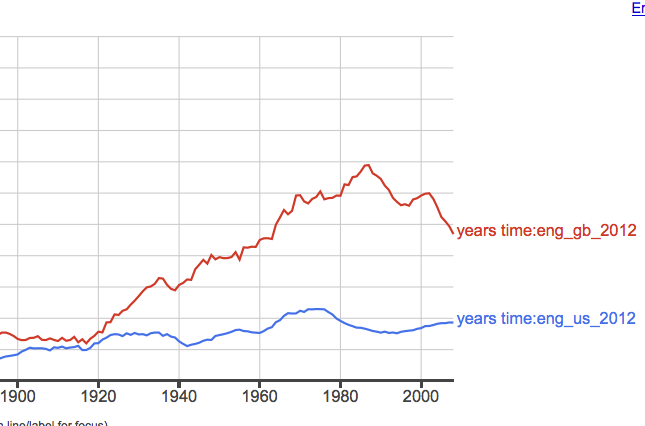

I know Dyson originates in the U.K. but still, gee whiz.

I know Dyson originates in the U.K. but still, gee whiz.