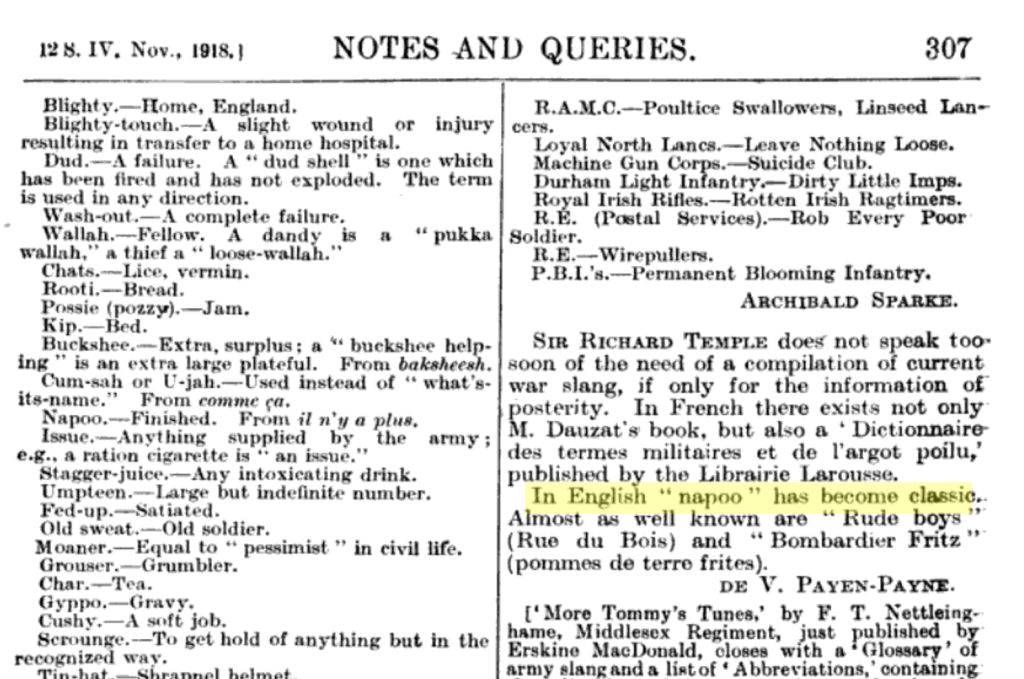

I happened upon a 1918 letter to Notes and Queries in which the correspondent, Archibald Sparke, noted that “quite a large number of new words have come into common use during the War” and offered a list. Here’s a part of it:

I’ve already covered “scrounge,” but a few of the others struck me as being common in the U.S. I’ll take a look at them all in the coming weeks, starting with the “cushy.”

The OED tells us that it derives from words in Persian and Urdu that connote pleasure or convenience, and suggests that etymologically distinct “cushion” or “cushiony” may also have had an influence. The definition for the most common sense is: “Of a job, situation, etc.: undemanding, easy; requiring little or no effort; (later) spec. involving little effort, but ample or disproportionate rewards…”

The specifically military sense predates the Great War, as the OED has a brilliant 1895 quote from the Penny Illustrated Paper: “He told me that I had got into a ‘cushy’ (easy) troop.” And Green’s Dictionary of Slang gives a 1912 example of a now familiar formulation: “A lot of them have rare cushy jobs.”

The OED notes an interesting World War I sense of “cushy”: “Of a wound: serious enough to necessitate one’s withdrawal from active duty, but not life-threatening or likely to have permanent consequences, such as disability.” It provides this 1915 quote: “When you are in the trenches a cushy wound..seems the most desirable thing in the world.”

This 1918 New York Times article uses an interesting noun form in the headline:

“‘CUSHIES’ FOR THE FRONT

“British Agitation to Make Holders of “Soft Jobs” Do Guard Duty.

“Henry W. Benson, a wool merchant who arrived yesterday from London on his way to Sydney, Australla, sald that when he left England there was a strong agitation under way to have all the holders of ‘cushy jobs’ sent to the Continent to do guard duty and let the men who have done the fighting and endured the hardships of the war come home.”

The first example I’ve seen of an American using the term is Green’s citation from Budd Schulberg’s 1947 novel The Harder They Fall: “My job with Nick was like a jail, a comfortable, cushy jail.” The New York Times first used the expression “cushy job” in 1964; since then, it’s appeared in the paper 103 times.

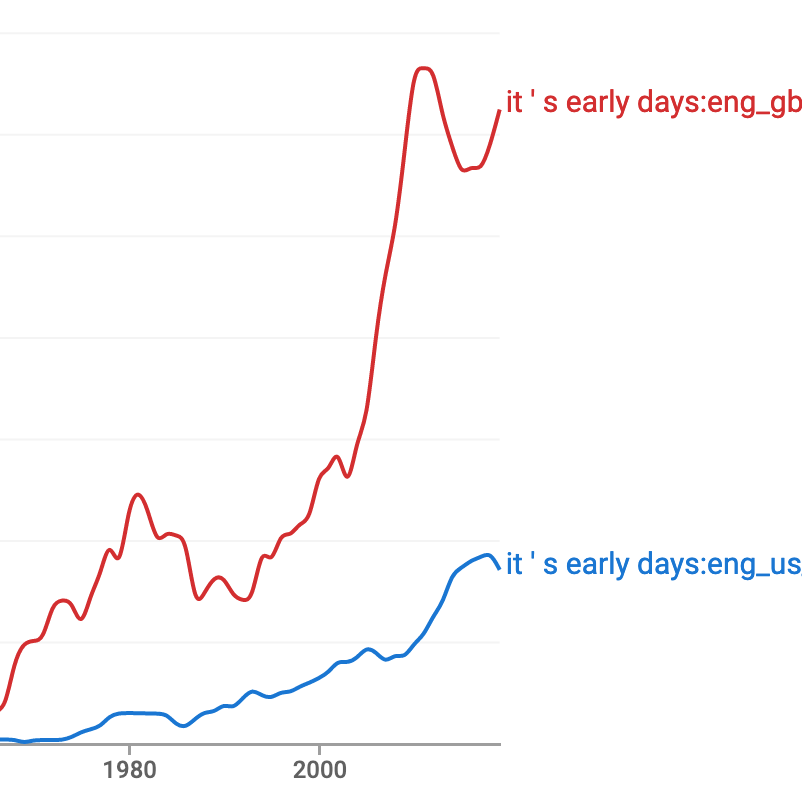

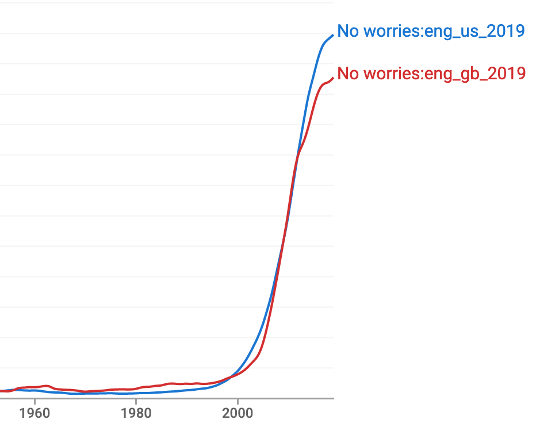

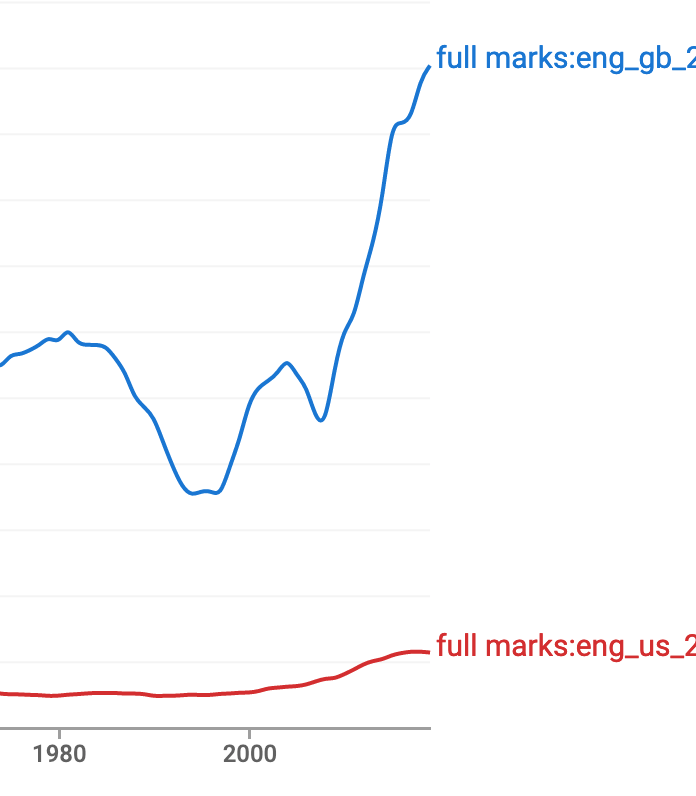

And so it isn’t surprising that Ngram Viewer shows American use picking up in the 1970s, and surpassing British use in the ’90s:

Next: “wash-out.”