The OG of British-American language comparison is Lynne Murphy, a U.S. native, professor of linguistics at the University of Sussex, author of the book The Prodigal Tongue and the blog Separated by a Common Language. On the blog she annually chooses two Words of the Year: a U.S.-to-U.K. export (this year it’s pronouncing the last letter of the alphabet “zee” instead of “zed”) and, what’s interesting for my purposes, a word or phrase that’s traveled from the U.K. to the U.S. The winner for 2025 is, drum roll please, the adjective “fiddly.”

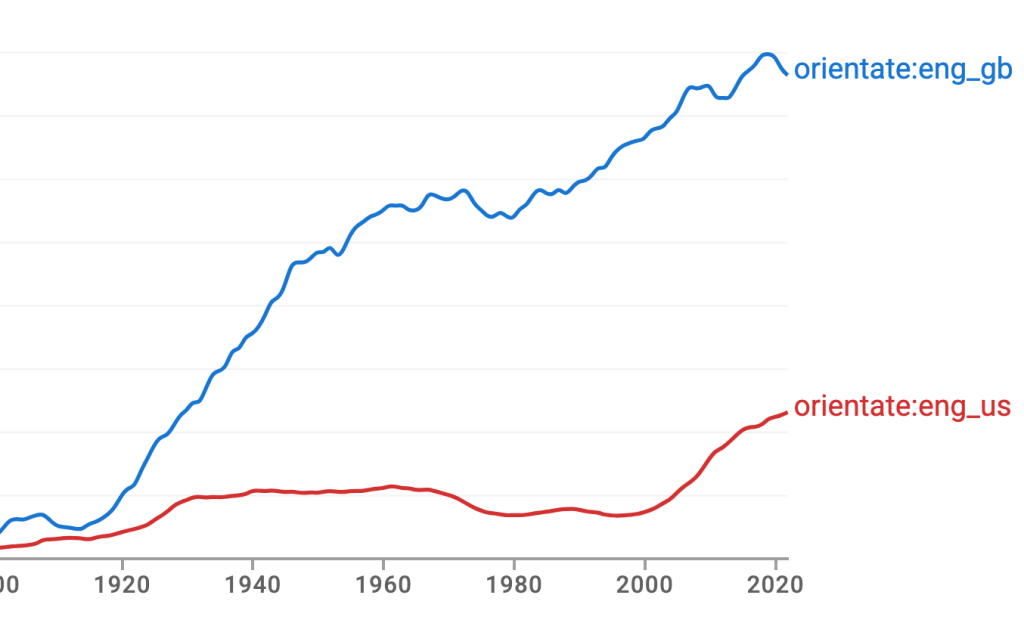

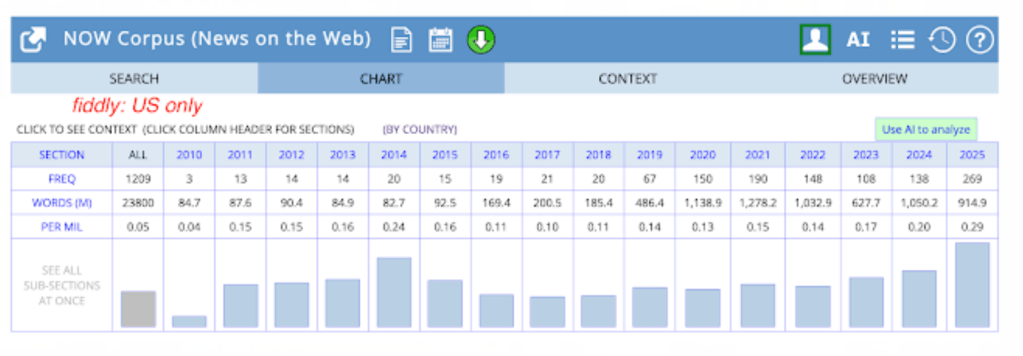

The OED defines it as “Requiring time or dexterity; pernickety” and has citations going back to 1926. Early uses were strictly British but it traveled to America by the 2000s and, as Lynne notes, I wrote about it on this blog in 2016., when a common phrase was “fiddly bits.” She observes that the News on the Web (NOW) corpus gives the impression that U.S. use had a bump in 2014, dropped off for a couple of years, and has been steadily increasing since then.

She looked at the ten most recent uses in the corpus and found that “Many things and activities … are fiddly: some kind of electronic device, rolling and stuffing a baked good, cleaning ear buds, a fictional mystery story, installing something on a bike, actions in video games, frostings and icings on Christmas cookies, using an infant car seat, paperwork.”

One commenter on Lynne’s post suggest a possible entry point for U.S. use of the word: board-game aficionados. He gives a link to a 2010 thread on the BGG (Board Game Geek) kicked off by someone commenting:

“I’ve seen people talk about how a game is ‘fiddly’, which usually means that they don’t like it as much…. So, what makes a game fiddly, and why should that detract from the game? Is chess fiddly because of all those pieces you have to move? Is Alea Iacta Est fiddly because you have to deal with all those dice? Is Dungeon Lords fiddly because of all those imps, adventurers, monsters, damage cubes, etc.? Dominion must be fiddly, because you have to shuffle so much. So what are your thoughts? Help me to understand.”

There are twenty-three responses, including this clear and non-fiddly one:

“I use the term and think it a nice summation to what most have voiced here: at discreet points in the game, players are required to perform the tasks listed in the rules. Those tasks, for one reason or another, are usually difficult to remember and sometime cause errors in play or recurring rules consultations. The number of bits isn’t necessarily the cause though. It just as easily can be caused by a litany of housekeeping at the ends of rounds (player A gets a free X cause he’s in last, player B moves up two because they lost dominance, player B also gets to choose a consolation prize from the items in board area 3.”

Thanks for clearing that up!