I refer to the intransitive verb that basically means “to appear,” possibly unexpectedly, and that can refer to a person, thing or concept (and not to the transitive form, e.g, “The search turned up a few artifacts” or “She turned up her nose and the cuffs of her jeans.”) I think of it as a Britishism mainly, I suppose, because there’s such a common and reliable U.S. equivalent: show up.

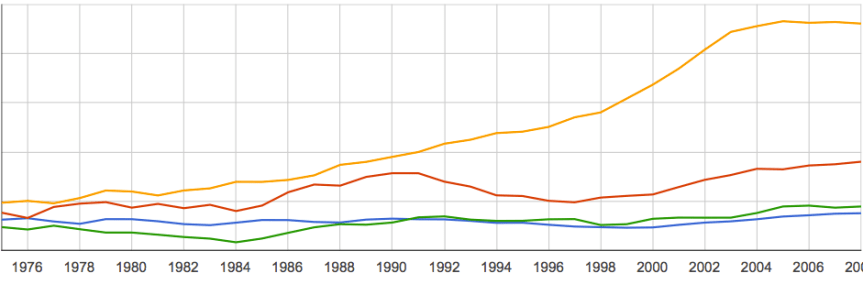

The Google Ngram above, which shows the relative popularity of showed up early and turned up early in the U.S. and Britain between 1975 and 2008 (the last year for which data is available), pretty much supports my sense. ( I stuck the early in there to avoid false positives in the transitive and other forms.) So does the OED, which reports turn up as having turned up very early in the eighteenth century. The dictionary cites an 1863 British newspaper report: “The Police have been astonished lately at the number of criminals who have turned up of whose previous career they knew nothing…” And the phrase was used memorably by Dickens in David Copperfield: “‘And then,’ said Mr. Micawber,..‘I shall, please Heaven, begin to be beforehand with the world,..if—in short, if anything turns up.’”

As for show up, the first citation is from the Lisbon (Dakota) Star, 1888: “Will Worden is expected to show up next week.”

The verb without up can mean the same thing, most often used as a negative or interrogatory. (“Did he show?” “Nope, he didn’t show.”) That’s certainly a popular slangy alternative in the U.S., but it didn’t originate here, according to the OED, which quotes Theodore Hook, The Parson’s Daughter (1833): “The breakfast party did not assemble till noon, and then Lady Katherine did not ‘shew.’” I reckon that was the source for the eventual U.S. show up.

Anyway, if and when Ngram offers data beyond 2008, I predict it will show a sharp uptick in U.S. turned up. My ears feel it has become the preferred alternative among the chattering classes. I was writing this on November 30 and found four separate uses in the N.Y Times that day:

- “…John McGraw’s futile attempt to trump the Yankees by finding a Jewish version of ‘the Babe.’ An exhaustive search turned up a prospect named Mose Solomon, likened in the press to an exotic animal. (‘McGraw Pays 50K for Only Jewish Ballplayer in Captivity.’)”

- “Two months later, though, Barnum turned up in Tennessee and, in June 1865, he signed an oath of allegiance to the federal government.”

- Books that writer Joe Queenan keeps as gags “mostly turned up over the transom at jobs I used to work at. ‘Hoosier Home Remedies’ is my favorite.”

And finally, this immortal sentence: “If Kristen Holly Smith turned up to your costume party in Dusty Springfield drag and started singing, there would be no mistaking the woman she was channeling.”

Faithful reader Cameron directed me to a quotation from an article on

Faithful reader Cameron directed me to a quotation from an article on

Reader Priscilla Jensen alerts me to this from the November 7 Wall Street Journal: “But [Barack Obama’s] opportunity will quickly go pear-shaped if the bond market loses confidence . . . ”

Reader Priscilla Jensen alerts me to this from the November 7 Wall Street Journal: “But [Barack Obama’s] opportunity will quickly go pear-shaped if the bond market loses confidence . . . ”