The OED’s first citation for this adjective comes from the 1964 movie tie-in The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night, by John Burke, and helpfully includes an etymology and partial definition: “‘I wouldn’t be seen dead in them. They’re dead grotty.’ Marshall stared. ‘Grotty?’ ‘Yeah—grotesque.’” The OED’s full definition: “Unpleasant, dirty, nasty, ugly, etc.: a general term of disapproval.”

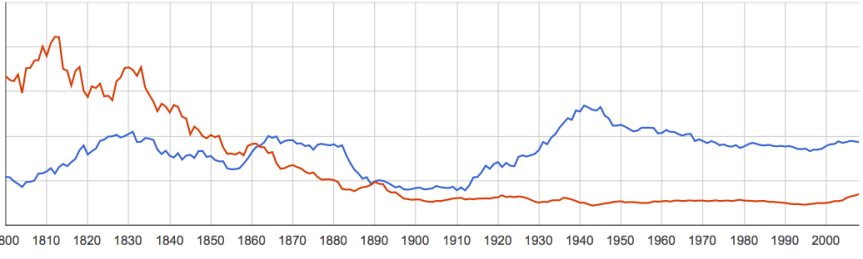

A Google Ngram graph shows that grotty is a dead Britishism, with steadily increasing U.S. use. That appears to have picked up in recent years, including in a piece about the HBO series “Girls” in today’s Philadelphia Inquirer: “Hannah is still waiting hand in foot on Adam (Adam Driver) in his grotty apartment.”

An April 2012 New York Times theater review by Eric Grode says the play’s setting, in “a wood-paneled living room in Paterson, N.J., is more strip mall than Vegas Strip. (Mimi Lien contributed the suitably grotty set.)”

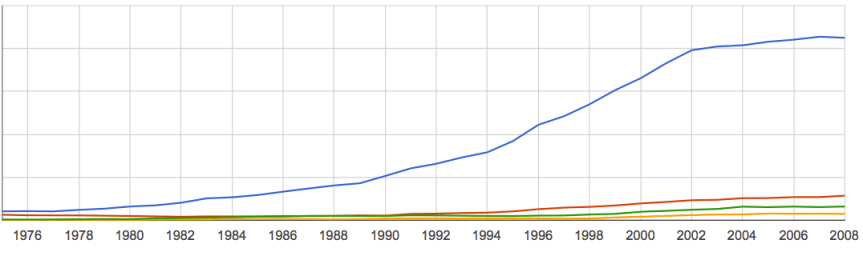

The reviewer’s name reminds me that there is more or less exact American equivalent, spelled, variously, grody, groaty, groady, and groddy, with all but the last rhyming with toady. The OED’s first cite for this is a 1965 Houston Chronicle but it gained immortality in the early ’80s, via Valley Girl Moon Unit Zappa and her immortal phrase “grody to the max.”

Is there any difference between grotty and grody? I leave a definite answer to wiser heads than mine, but I will note that all the OED definitions of grody refer to people and all but one of grotty refer to places.

But I found that the Susan Kamil quote wasn’t a one-off, as witness this from the Yale Daily News: “After winning every Ivy game this season, the women’s volleyball team is going from strength to strength.” (October 17, 2012) And this February 2102 quote from the Times’ David

But I found that the Susan Kamil quote wasn’t a one-off, as witness this from the Yale Daily News: “After winning every Ivy game this season, the women’s volleyball team is going from strength to strength.” (October 17, 2012) And this February 2102 quote from the Times’ David