(“Cali”=California. Bear=symbol of University of California.)

“Pulling”

The New York Times yesterday had an article about four UK television series (“Gavin & Stacey,” “Pulling,” “Second Sight,” and “Spy”) and one Australian one (“Rake”) that are being remade in the U.S. It interested me that ABC appears not to be giving a new title to “Pulling,” the original version of which the Times’ Mike Hale describes this way: “Featuring three unrepentantly randy women, it’s brutally frank about sex, booze and lowered expectations, while also being smart and raucously funny.”

The title thing intrigued me because I have never encountered that meaning of pull in the U.S. For the benefit of American readers, here’s the OED definition and citations:

I predict that if the show (which stars the excellent Kristen Schaal) ever makes it to air in the U.S., it will be with a new title.

Incidentally, Hale seems to have been inspired by his subject here to use not only randy but another NOOB, in this description of “Rake”: “The protagonist, now called Keegan Joye, will be played by one of American’s most gifted portrayers of kindhearted sleazeballs, Greg Kinnear.”

“Nutter” spotting

As seen on Twitter. (Jack Shafer is an American columnist for Reuters)

“Yoghurt”

I recently became aware of the product featured above. The thing that struck me as odd (as I believe it would most Americans) is the unusual spelling of what we know as yogurt. I suspected it was a Britishism because of Alan Rickman. To be more precise, there’s a scene in the movie “Love, Actually” in which Rickman is trying to buy some jewelry for a woman not his wife, and the sales clerk (played by Rowan Atkinson) won’t let him just get on with it. Rickman finally says in exasperation: “Dip it in yogurt, cover it with chocolate buttons!” He pronounces yogurt with a short o in the first syllable–that is, to rhyme with hog–and that’s consistent with the yoghurt spelling.

(If you want to hear Rickman say this line, check out this hilarious YouTube mashup:

)

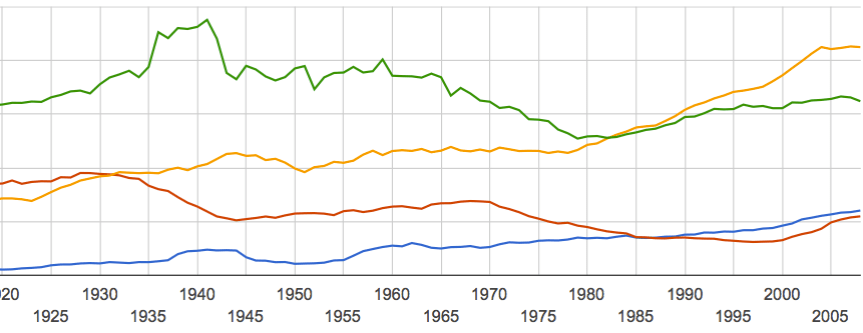

According to the OED, up until the mid-twentieth century, various spellings for the word (derived from Turkish) abounded, including yoghurd, yogourt,yahourt, yaghourt, yogurd, yoghourt, yooghort, and yughard. Subsequently, according to this Google Ngram chart, yogurt (red line) has prevailed in the U.S., and has roughly tied in the U.K. with yoghurt (yellow and green lines).

Google Ngrams only goes up till 2008, and when more recent data come in, I’m sure that as a result of companies like the Minnesota-based Mountain High, U.S. yoghurt (blue line) will be on the upswing.

The Culinary “Do,” cont.

Just spotted on East 11th Street in New York City, an up-to-the-minute example of do to mean prepare/offer/serve.

“On About”

The British say someone is on about something; Americans say going on, or going on and on. The first citation in the OED is from Rosamund Lehmann’s 1936 novel, Weather in Streets: “Marda’s always asking me why I don’t get a divorce… Last year she was always on about it.”

Welcome to NOOB-hood, bro.

- Kathryn Schulz (@kathrynschulz) writes on Twitter: “While I’m on about etymology (I’m always on about etymology): ‘adamant’ gets its root from ‘diamond’ — hard, unbreakable.”

- Kelly Dwyer on Yahoo Sports a couple of weeks ago: “I didn’t see a second of TNT’s Thursday night package, and didn’t hear what [basketball commentator Chris] Webber was on about.”

- “G. Funk”‘s comment on an article about professional wrestling on The Bleacher Report: “That’s why [the Ultimate Warrior] was the best. No one had a clue what he was on about, but everyone loved it.”

An early U.S. use came from the Rev. Al Sharpton, quoted in a 2002 New York Times article about a taped conversation he had with an undercover agent posing as a drug dealer: ”The guy had come to me. In the middle of conversation he started talking about how he could cut me in on a cocaine deal. I didn’t know what this guy was on about. I didn’t know if he was armed. I was scared, so I just nodded my head to everything he said and then he left.”

Always a groundbreaker, the Rev. is.

“Hoover” spotting; “Leapt”

Nancy Friedman alerted me to a passage from the February 22 New York Times because of the NOOB five words from the end.

As she rose from her chair at the Calvin Klein fashion show in Midtown Manhattan the other week, Jessica Chastain was all but engulfed by an onrush of journalists and celebrity groupies imploring the lanky, flame-haired actress for a word, a glance, a nanosecond of her time.

Stefano Tonchi, the editor of W, embraced her showily as cameras clicked and whirred. Tim Blanks, the editor at large for Style.com, thrust a microphone in her face, pleading for an interview, before a pair of overzealous handlers leapt onto the catwalk to spirit her away.

Yes, Ms. Chastain can Hoover that kind of attention.

But what also caught my eye was the British leapt at the end of the second paragraph; the traditional American spelling is leaped. Sure, the -pt form is gaining ground. Sticking with the Times, it has used leaped 45,800 times since it started publishing in 1851, compared to 13,100 for leapt. But in the last twelve months, the tables have turned: there have been 793 leapts in the paper and only 301 leapeds.

The Times is ahead of the curve on this. The Lexis-Nexis database of U.S. newspapers reveals 1231 leapts in the past six months compared to 1528 leapeds. But it seems clear that leaped better enjoy its dominance now, because it won’t last much longer.

“Pip”

A Reuters article, datelined San Francisco and posted yesterday, says Microsoft “managed to pip Facebook Inc in the survey – only 42 percent of young adults thought the world’s largest social network is cooler now than in the past. Twitter scored 47 percent, below Microsoft’s 50 percent.”

I heard about this on Twitter, where Kenneth Li provided the link and tweeted: “In which an american writer uses the word ‘pip.'”

What means this pip? I did a search on GoogleNews and this emerged:

That was not helpful, so I turned to the OED, which I should have done in the first place. The relevant definition is “To defeat or beat narrowly,” and the first citation is from 1838, in the journal “Hood’s Own, or Laughter from Year to Year”: “With your face inconsistently playing at longs and your hand at shorts,—getting hypped as well as pipped,—‘talking of Hoyle..but looking like winegar.’”

That settles the meaning. As for NOOB-itude, Kenneth Li was right to single this pip out. It’s an outlier for sure.

“Saviour” and “Nappies”

Now there’s a combination you don’t normally see, but they are, or at least seem to be, favorites of Amy Bishop, the American woman convicted of murdering three of her colleagues at the University of Alabama-Huntsville in 2010. Patrick Radden Keefe recently published a long article about her case in the New Yorker, and in it a line of dialogue spoken by a “pompous scientist” in one of Bishop’s unpublished novels:

“And you want to change nappies, wipe snotty noses, and shovel green glop into a baby’s mouth like any fat, stupid Hausfrau?”

If you are unfamiliar with the term and the context clues are insufficient, nappy is British for diaper. I don’t know if the pompous scientist is supposed to be British, but I can affirm that nappy has virtually never been used anywhere else in the U.S., even among the hipsters of deepest Williamsburg.

Elsewhere in the article, in discussing Bishop’s religious feelings, Keefe writes: “Amy told me she accepts Christ as her Saviour, and she has been reading the Bible in prison.”

The most common U.S. spelling is savior and has been since the 1930s. In the Google Ngram chart below, the green line is British use of saviour, red is U.S. saviour (note the NOOB uptick on the right), yellow is U.S. savior, and blue is British savior.

Despite the recent NOOB uptick in U.S. saviour, the u-less version is very much the standard here. The New York Times Style Guide mandates Savior in religious contexts, savior in secular ones (such as “the new goalie will be the savior of the hockey team”). The Associated Press Style Guide (followed by most U.S. newspapers) calls for lower-casing both. The New Yorker, true to its idiosyncratic self, calls for hockey saviors and a Christian Saviour.

The nappy may be Amy Bishop’s; Saviour is very much the New Yorker’s.