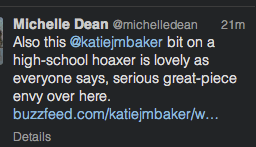

I have covered the use of BrE “bits” instead of the AmE “parts,” as in “the good bits,” “the naughty bits,” “lady bits,” “dangly bits,” etc. I’ve recently noticed another “bit” popular among journalists, as a synonym for a piece of work, traditionally and customarily shortened to a “piece.” David Carr of the New York Times is fond of it, and here it is from Michelle Dean on Twitter:  The OED suggests that the use of bit by itself in this way derives from tit-bits or tidbits, referring to a number or series of small items. The dictionary gives these citations:

The OED suggests that the use of bit by itself in this way derives from tit-bits or tidbits, referring to a number or series of small items. The dictionary gives these citations:

“Bob’s Your Uncle”

English reader John Barrett reports that in an episode of “Marvel: Agents of Shield,” the (American) character Phil Coulson says, “Bob’s your uncle.” John elaborates:

It was the last episode and he was describing how his team were [I told you John is English] supposed to infiltrate HYDRA headquarters, but his plan ran out of steam rather quickly and he ended with “and..er.. Bob’s your uncle!”

I’ve heard it rather too often in project meetings down the years – it’s often an euphemism for the cloud on the board marked “And then a miracle happens.”

My favourite was about 20-odd years ago, a hardware engineer (ex-RAF, which probably explained a lot ) was showing me a piece of networking equipment which one “plugs into the old wossname, hit the tit and Bob’s your uncle.”

The OED defines the phrase as “everything’s all right,” and though (or maybe because) it’s a quintessential Britishism, it’s shown up rather frequently in American pop culture, at least according to the Wikipedia hive:

In Mission Impossible: Ghost Protocol (2011), Benji Dunn uses the expression to cap his quick summary of Ethan Hunt’s plan to intercept the nuclear code transaction….

In the NCIS episode entitled “Truth or Consequences,” Agent Anthony DiNozzo uses the phrase to explain the unspoken communication between Agent Gibbs and Director Vance.

In season 11, episode 15 of the animated cartoon TV show The Simpsons, titled “Missionary: Impossible,” Homer uses the phrase when talking with Reverend Lovejoy…

In Monk, season 8, episode 7, “Mr. Monk and the Voodoo Curse,” Lieutenant Randy Disher explains how a victim named Robert died: “He opens the box, sees the doll, Bob’s your uncle, his heart just stops.” After that, Captain Leland Stottlemeyer ribs him, asking if that is a real phrase, or if he made it up; Disher protests that it’s an Australian figure of speech.

The origins of the phrase are murky. The OED doesn’t give any etymology, and the ones I’ve seen on Wikipedia and elsewhere are unconvincing, partly because they cite 19th century happenings and the phrase didn’t pop up till the 1930s.

And in this regard I believe I have a contribution. The OED’s first citation for “bob’s your uncle” is 1937, from Eric Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang. Subsequently, Stephen Goranson found a 1932 use and posted it to the American Dialect Society listserv. After poking around a bit, I found something even earlier: a song called “Follow your Uncle Bob, Bob’s your uncle.” The U.S. Library of Congress lists this as having been “written and composed by John P. Long, of Great Britain,” and copyrighted December 2, 1931.

#Micdrop.

Update: That’ll teach me to brag. Since posting this, I have learned that Gary Martin, who blogs as The Phrase Finder, has found an even earlier use. He writes: “The earliest known example of the phrase in print is in the bill for a performance of a musical revue in Dundee called Bob’s Your Uncle, which appeared in the Scottish newspaper The Angus Evening Telegraph in June 1924.”

I await an update of the OED entry. In the meantime, here’s a clip of Florrie Florde singing “Follow Your Uncle Bob”:

IWS

Incipient “Wanker” Spread, that is. An American friend (who works for a U.S. company) posted this photo on Facebook this morning, explaining that it’s a photo of the Post-It note that had been affixed to his keyboard overnight.

I asked for further details and he responded: “Still a mystery to me… though I suspect a British colleague who was displeased I left the TV volume on too loud.”

If more forensic information is unearthed, you will be the first to know.

Spotted on a Philadelphia Parking Authority kiosk

“Hullo”

I got a business e-mail the other day (from an American) that started out with a one-word sentence: “Hullo.” The U.S. version, of course, is “hello.” I had always associated hullo with mum, except I sometimes encounter “mum” here, and I’d never seen an American “hullo.” Until now.

Poking around on the web for examples, I almost immediately encountered this quintessentially British quote from the quintessentially British P.G. Wodehouse (the narrator is the possibly even more quintessentially British Bertie Wooster):

“Hullo, Bobbie,” I said. “Hullo, Bertie,” she said. “Hullo, Upjohn,” I said. The correct response to this would have been “Hullo, Wooster”, but he blew up in his lines and merely made a noise like a wolf with its big toe caught in a trap.

Hello (first citation 1827) and hullo (1857) both have the same etymology as the verb holler, according to the OED, as do the older variants hallo (first seen in Dickens, in 1841) and hollo (Shakespeare, Titus Andronicus). Interestingly, an even earlier version is holla, which has recently come back in full force. The most popular definition on Urban Dictionary gives three meanings, the relevant one being, “A word used to acknowledge the presence of a fellow companion.” This example is offered: “Is that mah boy ova there? HOLLAAAAA!”

Generally, hello is indeed generally American and hullo generally British, through Google Ngram Viewer suggests some nuance:

The decline in hullo use on both sides of the Atlantic suggests that my e-mail correspondent’s use of the word was a one-off–about as likely to catch on as the similarly Wodehousian abbreviation for the thing we used to talk on: ‘phone.

The decline in hullo use on both sides of the Atlantic suggests that my e-mail correspondent’s use of the word was a one-off–about as likely to catch on as the similarly Wodehousian abbreviation for the thing we used to talk on: ‘phone.

“Expiry date”

When the BBC did a piece a couple of years on British people’s most annoying Americanisms, “expiration date” instead of “expiry date” made the top 50. As Lynne Murphy observed, those people didn’t really have much cause for their annoyance, but the Google Ngram chart below indeed shows “expiration date” as preferred in the U.S. However, the two versions have been pretty close in Britain for the last fifty years.

Now, what of American “expiry date”? The graph shows it to be on the rise, and the ever-sharp-eyed Nancy Friedman reports a growing number of sightings, notably at the clothing and furnishings chain Anthropologie. I went to the company’s website and went far enough in the process of buying a $500 rug to come upon this:

At that point, I x-ed out of that tab as quick as I could and hightailed it out of there.

“Sport” sighting in New York Times

I’ve written before about the increasing U.S. use of sport rather than the traditional sports. National Public Radio’s Frank Deford tends to alternate the two in his weekly commentaries. But this headline from today’s New York Times would appear to herald a new level of acceptance for the singular form.

Variation on a Meme

“Quality” as an adjective was just one of the things that caught my attention during a recent visit to England. Another was this play on man with a van, spotted during on a vehicle parked near Pembridge Villas in London.

“Quality” (adj.)

On holiday in London last week, I was gobsmacked to come upon this:

The reason for my surprise was that, on my mother’s knee, I was taught that quality should not be used as an adjective but exclusively as a noun referring to a feature or characteristic of a person or thing. I haven’t been on my mother’s knee for a long time, but the injunction is still widespread. Bryan Garner’s entry on the word in Garner’s Modern American Usage reads, in its entirety: “When used as an adjective meaning ‘of high quality,’ this is a vogue word and a casualism <a quality bottling company>. Use good or fine or some other adjective of better standing.” For decades, one of the easiest and most efficient ways for novelists to convey that a character is a philistine has been to have him say something like, “I’m talking quality products here!”

But now I was seeing evidence that in England, quality is an adjective of perfectly good standing. It was meaningful that the sign was at a pub, for everything about this institution is supposed to signify history and tradition. In other words, the implication was that the usage had been OK for a long time.

And when I got home and checked my Oxford English Dictionary, I found that that is the case. The process started as early as Shakespeare, with the noun being used to mean high quality (“The Grecian youths are full of quality, And swelling ore with arts and exercise”) or, similarly, high birth or rank (“There are no men of quality but the Duke of Monmouth; all the rest are gentlemen,” 1671).

The adjective emerged roughly in 1700, meaning, in the OED‘s words: “With sense ‘of high social standing, of good breeding, noble’, as quality acquaintance, quality air, quality blood, quality end, quality friend, quality gentleman, quality horse, quality lady, quality living, quality pride, quality white, etc.” There are many citations in the 18th century (“The influence of Peregrine’s new quality-friends”—Smollett, Peregrine Pickle), but starting in the early 19th, according to the dictionary, this usage became “archaic.” The archaicness seems to have commenced being reversed in the United States; the OED cites a 1910 headline in an Ohio newspaper, “American is the quality magazine.” In Britain it became common in the 1960s to refer to The Times, The Guardian, and such as “quality newspapers,” as opposed to the red-top tabloids—so much so that a quality can be used as a noun (once again) to refer to such a publication.

A Google Ngram Viewer graph shows that the frequency of quality as an adjective (in American and British English combined) was minimal through 1920, rose gradually from 1920 to 1970, and exploded from 1970 through 2000:

One can name a couple of factors, besides British newspaper terminology, that surely contributed to the recent escalation. Business jargon certainly took to the adjective, with its quality assurance, quality management, and quality circles. It’s big in sports, too. One cannot follow a season in basketball or football without hearing incessant talk of “quality wins” or “quality opponents.” A popular statistic in baseball since the 1980s has been the “quality start,” referring to an outing in which a pitcher stays in the game for at least six innings, and gives up no more than three runs.

But the big kahuna is “quality time,” about which the OED says, “orig. U.S.: time spent in a worthwhile or dedicated manner; esp. time in which one’s child, partner, etc., receives one’s undivided attention.” The first citation is in 1972, but because it so directly addressed busy people’s anxiety about not spending enough time with their kids or spouses, it quickly became a buzzword, and by the mid-1980s, Frank Rich of The New York Times was deriding it as a cliché. Ngram Viewer shows that it’s more popular than ever. But I would bet that many if not most of the uses are ironic or derisive, suggesting that, like the perpetual-motion machine, the notion that quality time can compensate for sparse quantity time is but a dream.

“Nil”

Robert Siegel, the redoubtable National Public Radio host, took to the airwaves yesterday to denounce nil. Or, rather, to denounce “nil” and its

creeping penetration of American English thanks to the World Cup. Nil is a contracted scrap of Latin that survives in a few common bits of American English. We might say the chances of something happening are next to nil. Headline writers always in need of very short words sometimes use nil. But if I said, in the top of the third inning, the Nationals led the Cubs one-nil and then Chicago scored an equalizer the late Harry Carey and Phil Rizzuto [both baseball announcers] would both shout, “Holy cow!” in their graves.

As readers of this blog know, the “creeping penetration” of British soccer terminology is a rich subject, covered most recently here. On the “nil” question, Siegel, to his credit, didn’t just fulminate but brought in an expert, Katherine Connor Martin, head of U.S. dictionaries for the Oxford University Press. She added some historical perspective:

…in the beginning of the 20th century the way that Americans talked about soccer was not that different from the way that British people talked about soccer. And they used nil sometimes to describe a score. But we lost the knack for talking professionally about soccer during soccer’s decline over the course the 20th century and now I think that our journalists are picking it up on the fly. And there’s an uncertainty about where does British-English end and soccer terminology begin. Most people wouldn’t think it was odd, I think, to say extra time rather than overtime. That’s just how you talk about soccer.

Siegel’s other guest, an announcer for a Major League Soccer team, would have none of this. “I don’t use the term nil,” he said, “because when I say I’m going to the men’s room I don’t say I’m going to the loo.”