When tapes emerged of Donald Trump bragging of kissing women and grabbing them by their private parts without their permission, he said (by way of apology or explanation), “This was locker-room banter.”

Locker rooms all over America immediately spoke out in protest, but what caught my ear was banter. The word came up in this blog a couple of years ago in reference to the“cheeky Nandos” meme, which someone (facetiously) attempted to explain in lad-culture terms:

okay, its a friday night and you and the lads are out on the lash getting wankered in town, harassing women on the street, all wearing chinos, yeah? your top mate Ryan (proper LAD) wants to get something to eat so suggests pizza hut, bit old school and full of kids so banter wont be top notch, instead you get a cheeky nandos and the banter is sick as #bantersaurusrex #bantanddec #barackobanter #banterclaus #archbishopofbanterbury class night with the lads

But the word far predates Nando’s, having emerged in both noun and verb form in the late 17th century (etymology unknown). Green’s Dictionary of Slang quotes a 1698 slang compendium defining the noun as “a pleasant way of prating, which seems in earnest but is in jest.” Twelve years later, Jonathan Swift observed that the word was “first borrowed from the bullies in White Friars, then fell among the footmen”; he condemned it — along with kidney and bamboozle — as part of his brief to reform the English language.

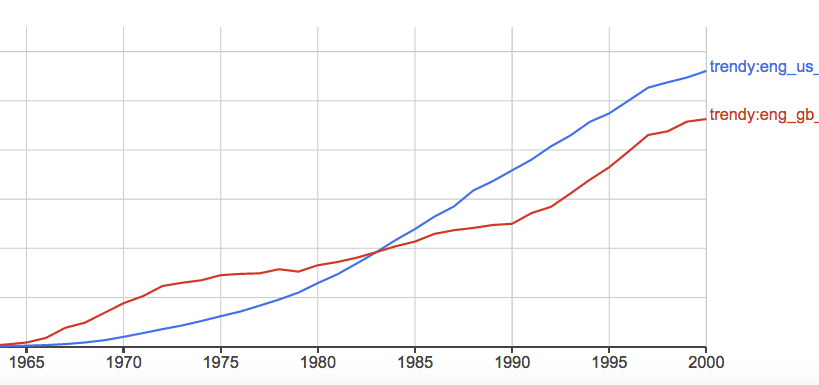

Swift’s complaint fell on deaf ears (as such complaints almost always do), and banter continued to be a popular word; Henry Fielding even used it as a character name in his satirical play The Historical Register of 1736. Things kept on in much the same way until the decade of the 2000s, when English lad culture adopted it as a favorite word for lads’ conversational back-and-forth, as in this scene from one of the Inbetweeners films (sort of a younger British version of the Hangover series).

Not that banter isn’t used by oldsters in the United Kingdom. Scottish officers purposefully employ banter when patrolling the mean streets; a delegation from the New York Police Department recently traveled to Glasgow to observe them in action. After members of London’s Garrick Club voted to continue to exclude women, one member said it was because he and his colleagues wanted to preserve the “camaraderie” and “banter” of the club.

Banter begat the phrase having the bants, which an Urban Dictionary contributor defined this way in 2010:

Engaging in the age old English tradition of bantering.

1. Fast paced witty exchanges, with tremendous japes had by all

2. General good times with clean fun and joviality

“We were all down the pub, having the bants when Pete came over and bought us another round. Great bants!”

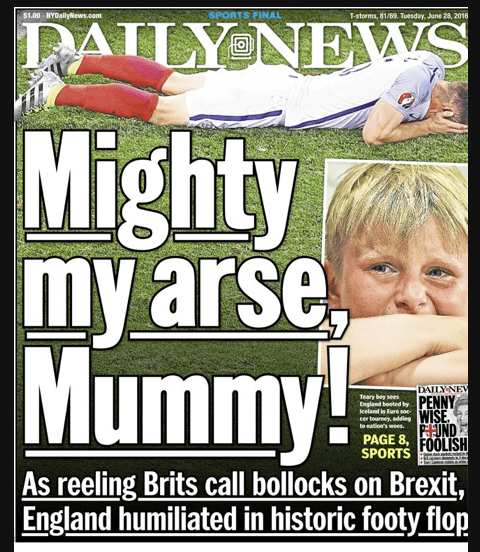

Meanwhile, banter became a sort of all-purpose excuse for boys behaving badly:

- Niall Horan of the boy band One Direction greeted female fans at Dublin’s airport, saying: “Remember the last time I walked out here? Remember the last time I walked out here and sprained my knee, you shower of c***s!” After getting some blowback, he tweeted, “It was just banter with fans who I think of more as mates.”

- On the British reality show I’m a Celebrity, one D-lister said of another, “What the f**k is this p***k doing in here? What’s he offering?’ Why the f**k are you in here? What are you? What sort of skill have you got?” His subsequent explanation: “We’re great friends, we are going to be for a long time — it was total banter.”

- In 2014, Cardiff City football manager Malky Mackay wrote in a text message, referring to a sports agent, “Go on, fat Phil. Nothing like a Jew that sees money slipping through his fingers.” The explanation from the League Managers Association? This and other messages were “sent in private at a time Malky felt under great pressure and when he was letting off steam to a friend during some friendly text message banter.”

A teacher banned the word, according to an article on the BBC website,

saying it had become an ‘excuse for inappropriate behaviour’ in his classroom, in Gorleston, Norfolk.

“If I catch somebody nicking someone’s pencilcase, calling another student a derogatory name or thumping them on the back, nine times out of ten I’ll be met with a, ‘Siiiir, it’s just bantaaaaaaah!’” he wrote on his blog.

A (male) poet was quoted in the article as saying the word had become “more downmarket than it used to be. It’s something I used to say quite a bit but it’s taken on quite a laddish connotation now.”

Even before last week, the Banter Excuse had started making its way across the Atlantic. A Brown University student accused of sexual misconduct said, as part of his defense, that he and the alleged victim had engaged in “sexual banter.”

Back in the 18th century, Swift wrote, “I have done my utmost for some Years past, to stop the Progress of Mob and Banter; but have been plainly born down by Numbers, and betrayed by those who promised to assist me.” If banter takes hold here and becomes the go-to excuse for having said racist, sexist, hateful, or otherwise horrible things, then I am going full-Swift on the word. Who’s with me?