It started when I sent an article from the sports news site New York Times sports site The Athletic to my tennis buddy Don Lessem, who occasionally uncorks an underarm serve. The article was about the top professional Sara Errani, who uses the same dare I say underhanded tactic. Don wrote back: “What’s ‘nous’?”

I was pretty sure he wasn’t misspelling “new,” but otherwise I didn’t know what he was talking about. But when I read the article all the way through, I found this sentence:

“Instead of letting her serve become a complete albatross, Errani has used her ground skills, tactical nous and the shock factor of a serve that regularly registers around 60mph (96.5kph) on the speed gun to reach the very top of tennis in singles and doubles.”

Looking up “nous” in Green’s Dictionary of Slang, I find that it means “instinct or common sense, as opposed to actual learning”; that it rhymes with “mouse”; and that there are more than two dozen citations for it in British and Australian sources, going back to 1704, but only one American one, from an 1878 book.

The explanation for its appearance in the Athletic article is simple. Here’s the bio of the author of the article:

“Charlie Eccleshare is a tennis writer for The Athletic, having previously covered soccer as the Tottenham Hotspur correspondent for five years. He joined in 2019 after five years writing about football and tennis at The Telegraph.” The Telegraph being a British newspaper.

And in fact there are more Britishisms in this one particular piece:

- Eccleshare calls the underarm serve “cheeky.”

- He gives the speed of Errani’s serve as quoted above, and lists Errani’s her as “5ft 5in (164cm).” An American publication would never give the centimeter or kilometers per hour figures. (Eccleshare also leaves out the spaces that normal Times style requires, but that’s too nerdy a topic to get into, even for me.)

- He talks about her being “broken to love,” meaning a game in which she was serving but didn’t win a point. I’m not sure, but I think the American version is “broken at love.”

- He uses logical punctuation when he quotes someone as saying Errani is “the brain of the team”.

- He uses single quotation marks, or inverted commas, when he refers to Errani of being one of the ‘Fab Four’ of Italian women’s tennis.

- He uses British spelling when he writes about a player who “practised,” rather than “practiced,” a particular shot.

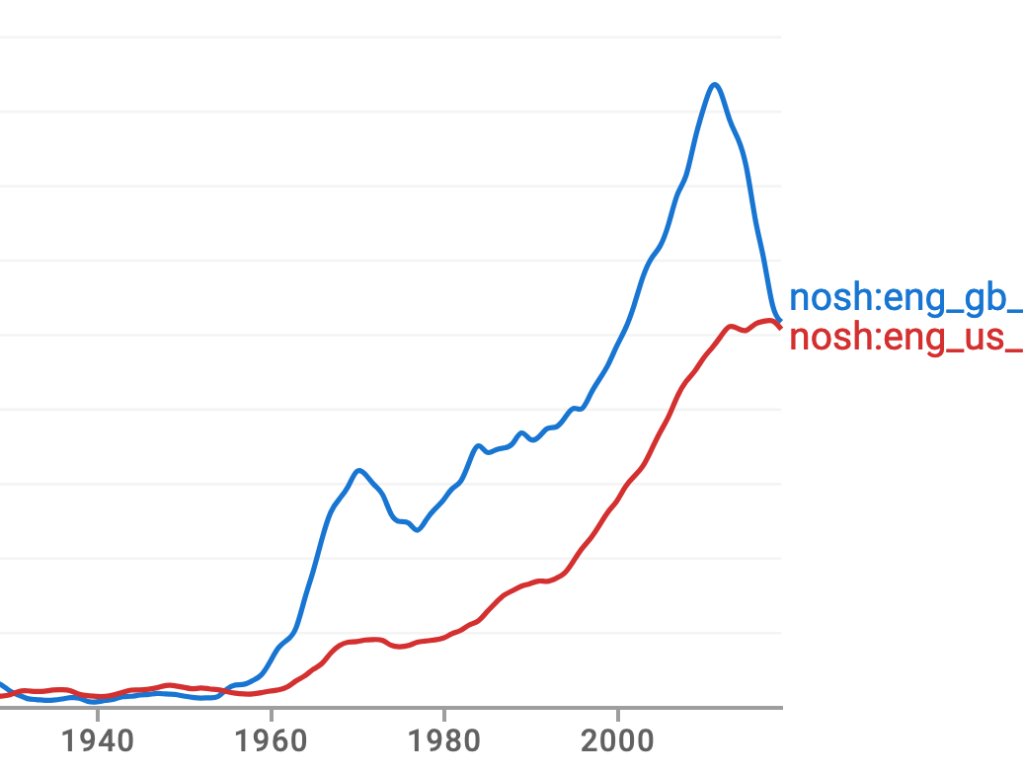

Now, I don’t really have a problem with any of this. Arguably, it makes the writing more colorful. But it does point to a new and robust conduit for NOOBs. Other than that the Times owns the Athletic and their staffs are separate, I’m not exactly sure of the precise relationship between the two entities, but I got to the Errani piece and all other Athletic articles via the Times home page, and Athletic content is in the searchable Times database.. However, it’s clear that that Athletic pieces aren’t subject to Times style rules or editing. As a result, in the coverage not only of international sports but also of Premier League and European football, the Athletic is poised to be a massive source of NOOBs.