There is really no excuse for Quartz, an American-based publication, to use “university” rather than “college” in this headline. For one thing, “university” is three words letters longer.

There is really no excuse for Quartz, an American-based publication, to use “university” rather than “college” in this headline. For one thing, “university” is three words letters longer.

In an interview with CNN, Tom Hanks commented on Donald Trump’s handling of a condolence call to the widow of a US. soldier killed in action:

“I’m only knowing what I read in the newspapers and what have you, and it just seems like it’s one of the biggest cock-ups on the planet Earth, if you ask me.”

The question came from Lynne Murphy via Twitter: “Have you been hearing any ‘sectioned’ in US?”

Me: “No. What’s it mean?”

Her: “Committed, in the ‘institutionalized’ sense.”

The reason she asked was that one of her Twitter informants, who goes by the handle @ahab99, had heard the word coming out of the mouth of American characters on the American-set Netflix series “Mindhunter.” And sure enough, in Episode One, the wife of a hostage-taker says, “I tried to get him sectioned on Sunday” An FBI agent, apparently hard of hearing, follows up, “You tried to get him sectioned?”

The OED definition of the verb is, “To cause (a person) to be compulsorily detained in a psychiatric hospital in accordance with the provisions of the relevant section of the Mental Health Act of 1983 or (formerly) that of 1959.” All the citations are from British sources, including the first one, from a 1984 article in a medical journal: “Before the 1983 Act came into being no social worker ever refused my request to come and see a patient with a view to sectioning the patient under the old section 29.”

I would venture to say that, until now, the word has never been used in an American context.

And how did “sectioned” get into “Mindhunter”? The answer turns out to be simple. The writer of the episode, Joe Penhall, was raised in Australia but has done all his previous work in British theater and film.

That’s all well and good, but it’s pretty odd, as @ahab99 observed, that “apparently nobody in production or on set said ‘wait, what’s “sectioned”?’”

I last discussed the British expression “on the day”–AmE equivalent: “on the day of the event,” or “on the day in question”–because it was used by an American writer who turned out to have spent twenty years in the U.K. Two years later, it’s shown up again, this time in a quote by since-departed U.S. football manager Bruce Arena, after his team failed to qualify for the World Cup:

“This game in my view was perfectly positioned for the US team and we failed on the day.”

Arena has never coached anywhere but in the U.S., but, as has been discussed here in several posts, many Britishisms have made their way into American soccer. “On the day” hasn’t achieved broad acceptance, but it’s a useful expression, and Arena’s use of it makes me elevate its status from “outlier” to “on the radar.”

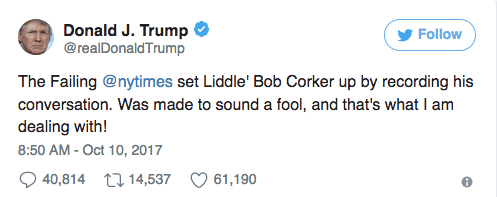

Usually, my sources for Not One-Off Britishisms are writers for the New York Times or the New Yorker, or some other American publication with aspirations to elegance or class. Imagine my surprise the other day to see our president tweet out what struck me as a palpable NOOB.

(Some background: Trump is in a fight with Republican Senator Bob Corker, who is slightly shorter than average, hence the “Liddle’.” The “d”s presumably represent an approximation of American flapping. The apostrophe is mystifying.)

What activated my NOObs-dar was “Was made to sound a fool.” It seemed to me that the standard American version of this would be “was made to sound like a fool,” while the “like” might be left out in BrE. To find out if I was right, I consulted my go-to source, American-born Sussex University linguistics professor Lynne Murphy.

She confirmed my sense and pointed me to a blog post she wrote on the subject in 2009. She observed:

I’ll quote [John] Algeo’s British or American English on the topic, “A group of copular verbs (…) have predominantly adjectival complements in common-core English, but also have nominal subject complements in British more frequently than in American.” In other words, in AmE or BrE, you could say I feel old (because my students told me yesterday that Brad Pitt is ‘a sexy old man’). You could also say I feel like an unsexy geriatric case, because the like phrase in that case plays an adjectival role in the sentence. But in BrE, you can also forgo the like and just go straight to the nouny part of the description….

Here are some examples showing more of this pattern:

sound: He sounded a complete mess. [Jeremy Clarke in The Independent]

look: Joey Barton has made me look a fool. [Oliver Holt on Mirror.co.uk]

Was Trump trying to sound an Englishman? I doubt it. Possibly he was echoing a common expression found in Twelfth Night (“This fellow is wise enough to play the fool”) and in the classic 1972 soul song “Everybody Plays the Fool.” It was also suggested when I raised the question on Twitter that the “like”-less construction is common in African-American English and/or in the rural South.

But I think I have a more likely explanation. Using “like” would have put Trump’s tweet at 142 characters. So he ditched it.

Friend of NOOBs Ben Zimmer points out a line in a New York Times article about Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter’s retirement: “His post-Vanity Fair plans involve a six-month “garden leave” (Mr. Carter is fond of Britishisms) and a rented home in Provence.” The link goes to a Wikipedia article saying the expression “describes the practice whereby an employee leaving a job – having resigned or otherwise had their employment terminated – is instructed to stay away from work during the notice period, while still remaining on the payroll.”

The original form was “gardening leave.” The OED gives a 1981 citation from The Times (the British newspaper), the inverted commas indicating it was a recent coinage: “There are too many senior officers on permanent ‘gardening leave’.” The Wikipedia article says that the expression gained popularity through its use in a 1986 episode of the TV series “Yes, Prime Minister.” The OED’s first citation for the shortened “garden leave” is a 1990 Financial Times article. For more background on both variants, see this 2010 post by Nancy Friedman.

All OED citations for both versions come from U.K. sources, but they show up now and again in the New York Times, for example in a 2011 article about a Goldman Sachs executive who had “to take a paid 60-day leave before he could start at Dealbreaker [a satirical blog], a common industry waiting period referred to as a ”garden leave.”’

I was interested to learn about this expression because I’m currently undergoing it myself. I’ve retired from the University of Delaware, which allows prospective retirees to take a sabbatical at reduced pay before walking out the door. UD’s slightly morbid name for this period: “terminal leave.”

A few days ago, Louise Linton, the wife of U.S. Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin, got into trouble for posting this picture on Instagram:

The trouble stemmed from her hashtagging various items of her designer clothing–weird and creepy in itself, all the more so when accompanying a picture of getting off a U.S. military jet with official government markings.

What caught my eye was the reference to Tom Ford “sunnies”–sunnies being Australian shorthand for sunglasses. All citations for the term in both the Oxford English Dictionary and Green’s Dictionary of Slang are from Australian or New Zealand sources.

Linton is a native of Scotland who has lived in the U.S. for more than fifteen years. Did she pick up “sunnies” in Scotland, or is the term prevalent in the U.S. circles in which she travels? Please weigh in if you know.

Every day, the online Merriam-Webster dictionary chooses a “Word of the Day.” Yesterday it was “nobby,” which M-W defined as “cleverly stylish; chic, smart.” It derives from the noun “nob,” meaning a person of wealth or social distinction. (Interestingly it doesn’t appear to be etymologically related to “snob.”) There was no mention of the word being a Britishism, but it is. It doesn’t appear in the archives of the New York Times, and the only quote M-W gives is from the British magazine The New Statesman: “Sponsorship of nobby events seems to be the favourite PR trick for City firms in the soup.”

Similarly, almost all the citations in the Oxford English Dictionary are from British sources. The exceptions are the American Anglophiles Cole Porter (“Nowadays it’s rather nobby/To regard one’s private hobby/As the object of one’s tenderest affections”) and S.J. Perelman (“A serried row of floodlit edifices..trumpeted to the newcomer that he was in the nobbiest winter playground ever devised”).

Incidentally, the OED notes in its definition that the word is “In later use depreciative,” that is, mocking. Merriam-Webster appeared to be unaware of this and took some heat on Twitter:

Shades of “baby bump.” Once again, a singsongy term (that one alliterative and prenatal, this one rhyming and post-) much loved by the Daily Mail and other British tabloids has made its way to the U.S. Unlike the very popular “baby bump,” this new one doesn’t have much of a presence over here–where the preferred affectionate term is “mommy,” not “mummy”–but being featured in an NPR story a couple of days ago may change that.

Don’t get me wrong. It isn’t my place to comment on any exercise new mothers (or anyone else) choose to undertake. But let’s not take away their dignity. The NPR story says of this condition, “It turns out the jelly belly actually has a medical term: diastasis recti, which refers to a separation of the abdominal muscles.” So, rather than cutesy terms like “jelly belly” or “mummy tummy,” can’t we just call it what it is?