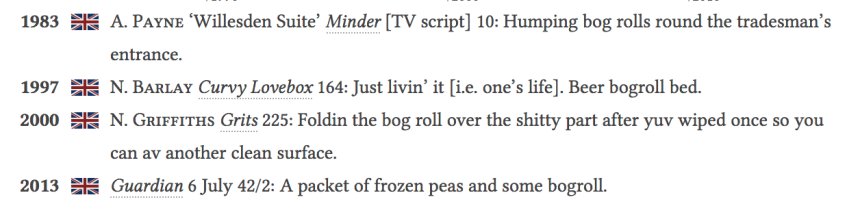

As I mentioned when discussing “cheesed off,” “browned off” is a similar term meaning fed up or annoyed. Both The Oxford English Dictionary and Green’s trace it to British sources, originating no later than 1938. That was the publication date of James Curtis’s novel They Drive By Night, this line from which both reference works quote: “What the hell had he got to be so browned off about? He ought to be feeling proper chirpy.”

But there is evidence of earlier use. The OED quotes Eric Partridge’s Dictionary of Slang (1961) as labeling the expression “Regular Army since ca. 1915; adopted by the RAF ca. 1929.” However, the dictionary sniffs, “pre-1938 printed evidence is lacking.” Green’s quotes a letter written in 1940 by Mrs. Jean Green in Hunsur, Mysore, in India, and published that year in American Speech: “To brown off or to be browned off was first heard by me in Army circles at Aldershot [England] in 1932, and when I came out to India later in the year it was also used in Bangalore. Since then I have used it often, but gave it up a year or two ago, thinking it was overdone and dated.”

Much as one would like to, one cannot take Mrs. Green’s word for it that browned off was used in 1932. I can, however, provide the OED with a pre-1938 use in this line of dialogue from another James Curtis novel, There Ain’t No Justice, published in 1937: “All right, all right, all right, only fer Christ’s sake lay off of me. I’m feeling proper browned off. Be flying off the handle, any minute now.”

As for American adoption, “browned off” is not in wide use today on on either side of the Atlantic but appears to have been picked up by American soldiers in World War II–hence my categorizing it under “Historical NOOBs.” Green’s quotes a Norman Mailer letter from 1948 in which he lumped the expression in with a bunch of euphemisms he had disdain for: “Words liked [sic] browned-off, fouled-up, mother-loving, f—, spit for shit are the most counterfeit of currencies.” I can antedate that, too. On October 3, 1943, The New York Times published an article by Milton Bracker called “What to Write the Soldier Overseas.” Right at the get-go, Bracker takes up the topic of “Dear John” letters. He notes:

I discussed the foregoing in a post for Lingua Franca, the Chronicle of Higher Education‘s blog about language and writing. Then I proudly tweeted my James Curtis antedate.

Well, my moment of triumph lasted four hours and seven minutes. I had tweeted my find at 9:18 PM Eastern Daylight Time, and at 6:25 AM Greenwich Mean Time, Jonathon Green, editor of Green’s Dictionary, responded:

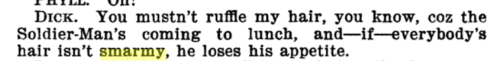

As Jonathon suggests, the item is a bit difficult to decipher. Tommies is slang for common soldiers in World War I, and Kitchener’s men refers, Wikipedia says, to the so-called New Army, “an (initially) all-volunteer army of the British Army formed in the United Kingdom from 1914 onwards following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War in late July 1914.” Bob down is trickier. Christopher Moore, in Roger, Sausage and Whippet: A Miscellany of Trench Lingo From the Great War, says it means to take cover, on the approach of enemy aircraft. That’s consistent with a use in a 1915 British book called Soldiers’ Stories of the War: “The whole of the advance consisted of a series of what might be called ups and downs — a little rush, then a ‘bob down.’” After the war, it took on a broader use, according to Jonathon Green’s forebear, Eric Partridge, who writes in A Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English that “Bob down — you’re spotted” was a catchphrase, dating from around 1920 , meaning “Your argument (excuse, etc.) is so very weak that you need not go on!”

As for “browned off,” it doesn’t seem in the newspaper item to have the later sense of angry or annoyed. Jonathan’s best guess was: “‘brown off’ = for a veteran to defeat a rookie; the ‘old sweat’ would have served in India or elsewhere in Empire and thus be literally brown, i.e. sun-tanned. Probably WW I army use only.”

He followed his first tweet up with an image of a letter to the Portsmouth Evening News, December 10, 1935, that definitely used browned off in the annoyed sense, thus antedating my antedate. Oh well, it was nice while it lasted. It’s a response to a previous letter by a correspondent who called herself or himself “Browned Off,” indicating that the expression was already somewhat common. (The quotations marks around “six years inland in sweltering heat” indicates it was a well-known quote, too, but a Google search yields nothing.)

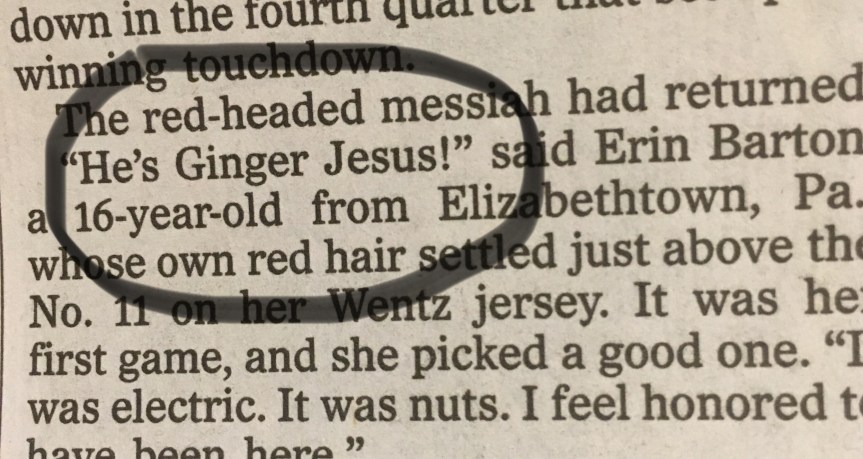

That leaves one mystery. Green’s entry for browned off lists as one of the few American citations a line from Chester Himes’s 1969 crime novel Blind Man With a Pistol: “By the time the sergeant got to the tenants in the last room he was well browned off.” I noted in my Lingua Franca post that it seemed odd that Himes — an African-American, born in Missouri in 1909 — would have used not only browned off but also the intensifier well, especially in reference to a New York City policeman. When well is placed in front of an adjective, I associate it strictly with British writers and speakers, a sense that’s confirmed by Brigham Young University’s Corpus of Global Web-Based English. I searched the GloWbE for the phrase well happy, meaning “very happy.” There were zero hits from American sources and 28 from British ones, including this line from a 1988 document, The Manual, that contains four Britishisms: “Nobody would dare ask to be paid for having a laugh [1], acting the lad [2] — buy them a pint [3] and they will be well happy [4].” (Americans do use a similar well in front of past participles: “That ball was well struck”; “It’s a well-written book.”)

So how did Himes come to use this well? The mystery was solved, to my satisfaction, by Lingua Franca commenter 99Luftballoons, who noted that Himes lived abroad — first in France, then in Spain — from 1953 till his death in 1984 and that his companion and eventually wife in his later years was Lesley Packard. Her 2010 obituary in The Guardian reports, “After he suffered a stroke, in 1959, she left her job to nurse him back to health and cared for him for the rest of his life, as his informal editor, proofreader and confidante.”

It almost goes without saying that Packard was British.