In a comment to the previous post, on “whilst,” David Collard posted a link to a Times Literary Supplement blog post he wrote about his aversion to the word. Mr. Collard (whose spelling, logical punctuation, and use of the term “car park” tag him as British) noted:

“Whilst” is a word that never fails to irritate me, not simply because it’s an unnecessary and unattractive alternative to “while”, but because it’s employed as part of the pervasive culture of “customer care”. Here are three examples gleaned on a quick stroll around my neighbourhood this morning:

“This car park is reserved for customers whilst using the bank.”

“We apologise for any inconvenience whilst work is in progress.”

“Please wait here whilst your order is being processed.”

And a very familiar recorded telephone message: “Please hold the line whilst we try to connect you”.

American readers will find “whilst” merely quaint, and possibly affected, but on this side of the pond there’s a terrible tendency to prefer “whilst” to “while”, especially in public notices. It’s not simply that “whilst” is outdated, it comes with a certain hidebound attitude – prim, supercilious, self-righteous.

He went on to say, “Compare the not-unrelated words: ‘amongst’, ‘betwixt’, ‘unbeknownst’. Especially ‘unbeknownst’. They all share – for me at least – a false Arthurian whiff, a saloon-bar, fake bonhomous resonance, something that implies thoughtful reflection and careful discrimination and eloquence but usually expresses the opposite.”

I agree on “amongst.” As for his other two examples, I’ve always associated “betwixt” exclusively with the expression “betwixt and between” (the way I never hear about crannies apart from nooks, or caboodles apart from kits). But when I looked into it, I discovered “betwixt” is indeed used on its own, and I’ll return to it in a future post.

As for “unbeknownst,” I think of it as normal, or “unmarked,” commonly used as it is in the first hit in a Google News search, a January 8 U.S. newspaper article about a daughter whose father beat her and instructed her to lie about it: “Unbeknownst to [the father], his daughter recorded the incident with her cellphone, authorities said.”

But it turns out “unbeknownst” is a word with a history, occasionally a contentious one, as in David Collard’s critique. Part of the trouble is there’s supposedly an older, more straightforward equivalent: “unknown.” That’s to some extent true. “Unknown” dates to the 14th century. But it has two distinct meanings. One is that a piece of information, or a person, is simply not known, as in this 1865 quote from a geology journal: “I have an anthozoan from the carstone of Hunstanton; its species unknown to me.”

The other, slightly different meaning is defined this way by the OED: “In parenthetic adverbial phrases or with adverbial force (chiefly with to, of, specifying the person or group to whom the fact or information is not known): without the knowledge of.” The dictionary cites this line from a 1672 medical text: “The Patient, unknown to me, pursued his intention.”

Perhaps you can see the problem in that sentence. On first read, it might seem that the patient is unknown to the writer. That’s obviously not true, so one figures out “unknown” here means “without the knowledge of.”

In order to address that ambiguity, I believe, two similar words sprang up in the early 18th century, both deriving from the Anglo-Saxon word for “know,” “be-knowen.” The first is “unbeknown.” The OED has a 1637 citation for “unbeknowne,” but that’s an outlier as the next one isn’t until 199 years later, a line of dialogue in Dickens’s Sketches by Boz: “If my ‘usband had treated her with a drain..unbeknown to me, I’d tear her precious eyes out.”

As for “unbeknownst,” the first OED citation is a line from an 1848 letter by the English novelist Elizabeth Gaskell: “You don’t see me, but I often am sitting in the rocking-chair unbeknownst to you.” I can antedate that. It’s used in the “not known” sense in this passage from an 1832 book, Wacousta: or, The Prophecy. A Tale of the Canadas, by Major John Richardson, whom Wikipedia calls “the first Canadian-born novelist to achieve international recognition.”

The first example I’ve found of the “unbeknownst to” form is in a piece, credited to the presumably pseudonymous “Toby Allspy,” in an 1837 edition of Bentley’s Miscellany, which was edited at the time by Charles Dickens: “he ‘d paid for it with an old coat unbeknownst to his valet.”

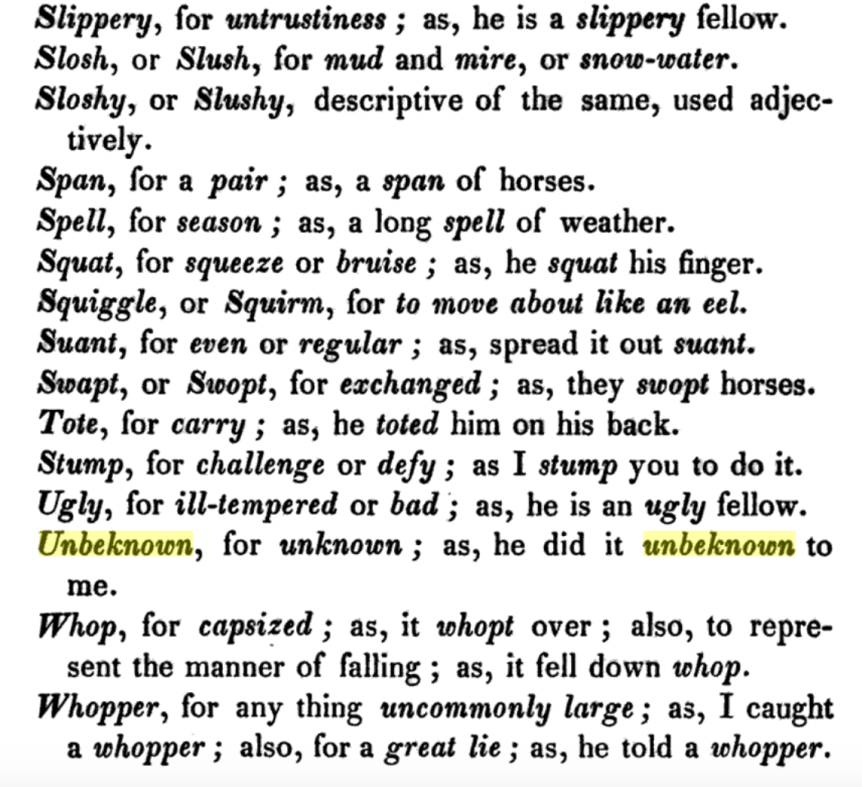

As for the national character of the two words, in 1842, six years after Gaskell’s use, “unbeknown” shows up in a grammar book published in Boston, in a list of “American Vulgarisms, Improprieties, &C.” Some of the vulgarisms have stuck, some not, as you can see from this screen shot:

Five years after that, in another American grammar book, by Seth Hurd, “unbeknown” is listed as one of the “Common Errors of Speech.”

But wait: in 1875, “unbeknownst” turns up as an entry in a book about the language of Sussex, England.

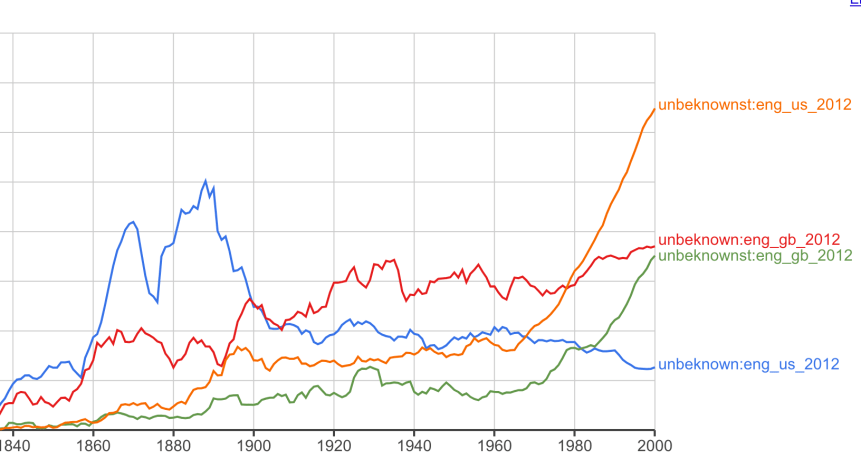

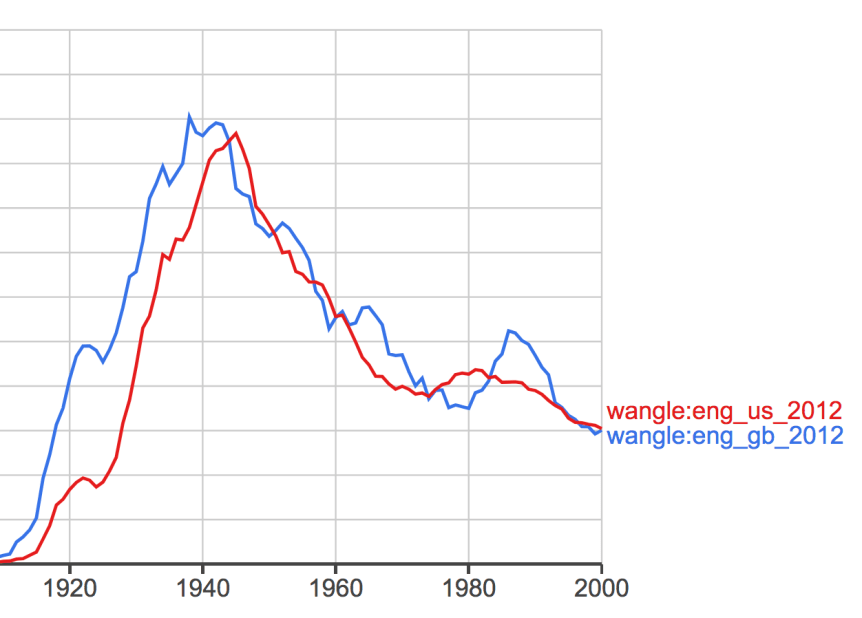

A Google Ngram Viewer graph tells the broader tale:

Let me try to parse it: in the late 1800s (as the books quoted above suggested), “unbeknown” was quite popular in the U.S. (blue line) and somewhat less so in Britain (red line). American “unbeknownst” (orange line) caught up to “unbeknown” in the 1940s and ’50s, caught up in the late 1960s, and took off from there. British “unbeknownst” was about to equal “unbeknown” in 2000 (the last year for which Google Ngram provides reliable data) and presumably has left it in the dust by now, much to David Collard’s displeasure.

Finally, do I agree with his critique? Not really. I still think “unbeknownst” a useful and inoffensive term, and definitely better than “unbeknown,” which sounds odd. But, of course, I’m an American.

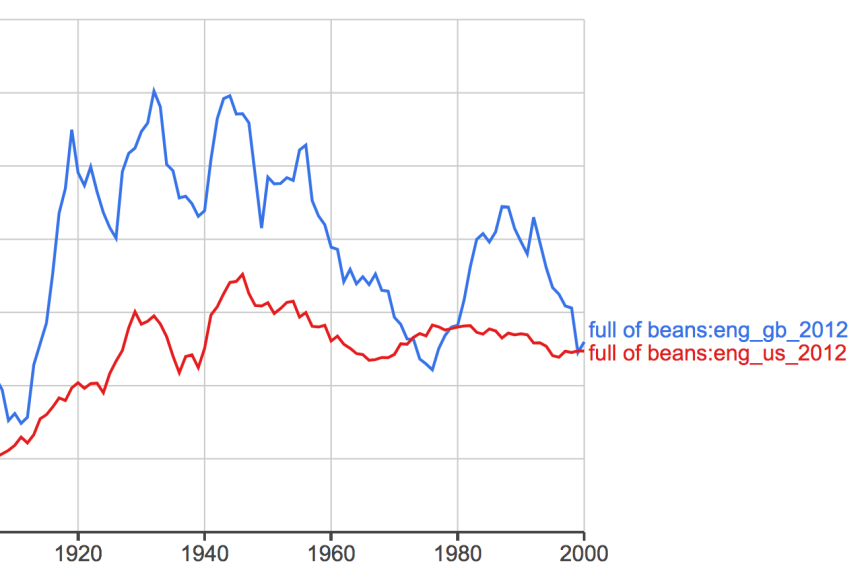

And here’s the one for “scrounge”:

And here’s the one for “scrounge”: