[When it was early days for this blog, I tended to write quite short entries. So I’ve been going back and updating and expanding a few of them.]

This is a classic example of an early NOOB that caught on because it’s better than all the American equivalents. “Perfect,” “exactly right,” “right on the money,” “flawless”: they’re all either weak, vague, or worn-out.

The OED has some early twentieth-century examples for “spot-on,” all British, in more or less technical senses, like this one from 1936: “We..have three variables, namely, the oscillator inductance, the parallel trimming condenser, and the series padding condenser, and three frequencies which are to be ‘spot on’.” In the ‘50s, the term began to be used as a more general adjective (“the performance was spot-on”) or interjection, as in this from Alan Sillitoe’s 1958 novel Saturday Night and Sunday Morning, quoted in Green’s Dictionary of Slang: “Arthur screwed his sandwich paper into a ball and threw it across the gangway into somebody’s work-box. ‘Spot-on’, he cried.”

The first American use I’ve been able to find was the opening of a 1985 New York Times restaurant review:

“’Oh, it’s a mixed bag.’ This was the reply I got when I telephoned Eton’s, the luxurious new restaurant in Englewood Cliffs, to ask what kind of food we would find there. As it turns out, the gentleman on the telephone was spot on.”

A lot of the early American uses were in food contexts, as in this from Los Angeles Magazine in May 2000: “For the lemony, pan-seared garlic chicken with baby spinach and a mashed potato gratin ($21), he suggests the ’97 Edmeades zinfandel, which is a spot-on pairing.” But three years after that, when it was featured on HBO’s The Wire, the term still wasn’t widespread. The late language commentator Geoffrey Nunberg, speaking on NPR’s “Fresh Air,” described its use in the series:

“Detective Jimmy McNulty is posing as an English businessman in order to bust a Baltimore brothel. He speaks in a comically bad English accent, the inside joke being that McNulty was actually played by the English actor Dominic West. Before he goes in, his boss Lt. Daniels and Assistant DA Rhonda Pearlman are prepping him for his role and giving him the signal to have them come in to make the arrests:

“Lt. Daniels: It’ll be your call when we come through the doors. You want us in, you say … [turns to Pearlman] what was it?

“Pearlman: “Spot on.” It means “exactly.” And remember, they have to bring up the money and the sex first, then an overt attempt … to engage.

“McNulty (in an exaggerated English accent): Spot on!”

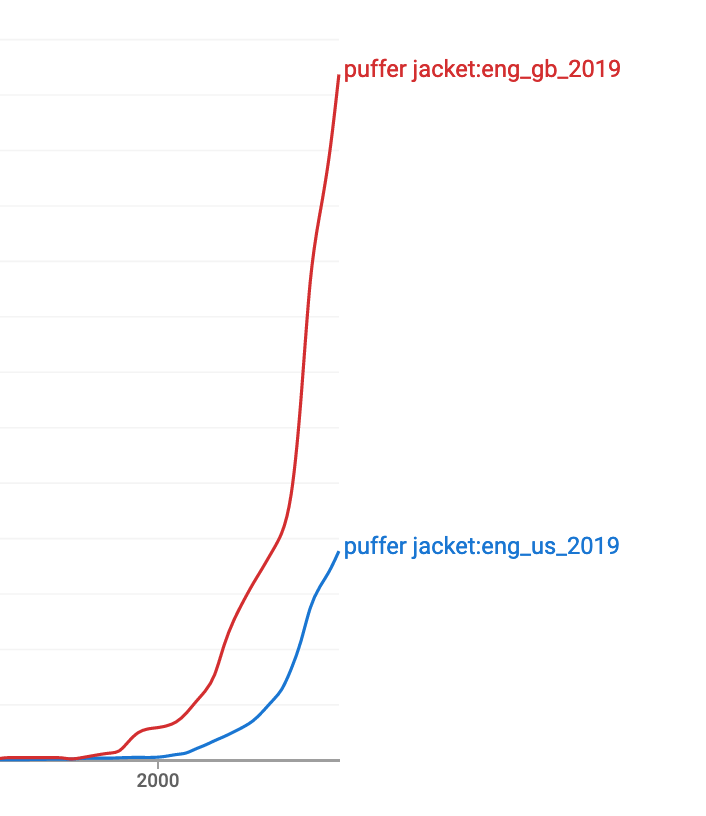

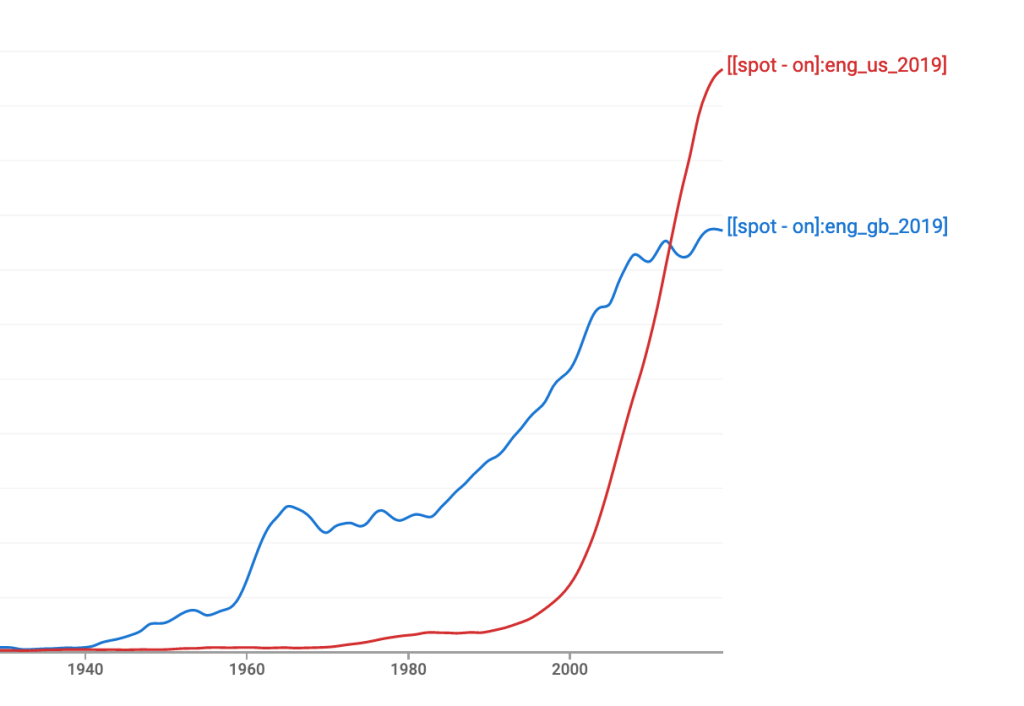

Well, things have changed a lot in two decades, as this Ngram Viewer chart shows:

In other words, as of 2012 or 2013, U.S. use topped British use. Supporting what I said at the top: in some situations, “spot-on” is, well, spot-on.