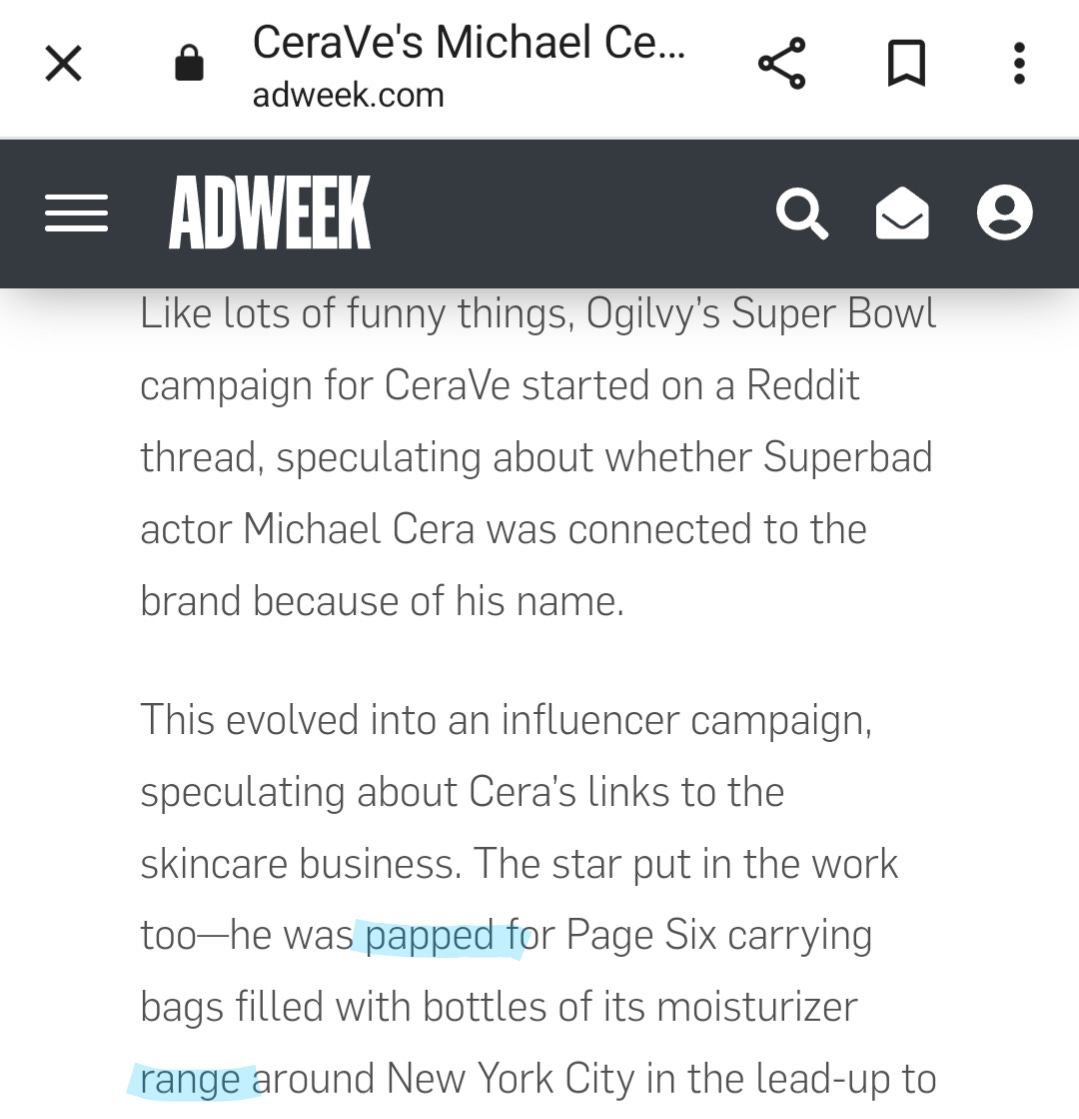

My book Gobsmacked: The British Invasion of American of American English–which is of course based on this blog–has gotten a lot of nice attention in the couple of weeks since it’s been out. I plan to do a post with some of the links to articles, reviews, and podcasts soon. But the piece by The Economist‘s “Johnson” columnist–Lane Greene–deserves a post of its own. The title is “Americans Are Chuffed as Chips at British English.” But I’m the one who’s chuffed, especially because it’s being so widely read.

This link will take you to the piece. There’s a paywall but also a free trial subscription offer, plus seemingly you can read it for free if you register. But if you can’t be arsed (or asked) to do that, here it is.

British intellectuals enjoy bewailing the influx of Americanisms into the language of the mother country. The BBC once asked British readers to send in the Americanisms that annoyed them most and was flooded with thousands of entries, including “24/7”, “deplane” and “touch base”. Matthew Engel, a writer who had kicked off the conversation with an article on unwanted Americanisms, even turned the idea into a book, “That’s the Way It Crumbles”, in 2017.

The furore—which Americans would call a furor—seemed to die down. But in September Simon Heffer of the Daily Telegraph revived it with a column and book exploring Americanisms, a trend he situates “in the past 15 years”. His language evokes violence, bemoaning American words’ “poisoning”, “linguistic assault”, “conquest” and “penetration”. In the end, though, even the hyperbolic Mr Heffer concedes that Brits are, in fact, “willingly adopting” these words, especially via two channels associated with America: digital technology and “corporatespeak”. He just wishes his countrymen would stop.

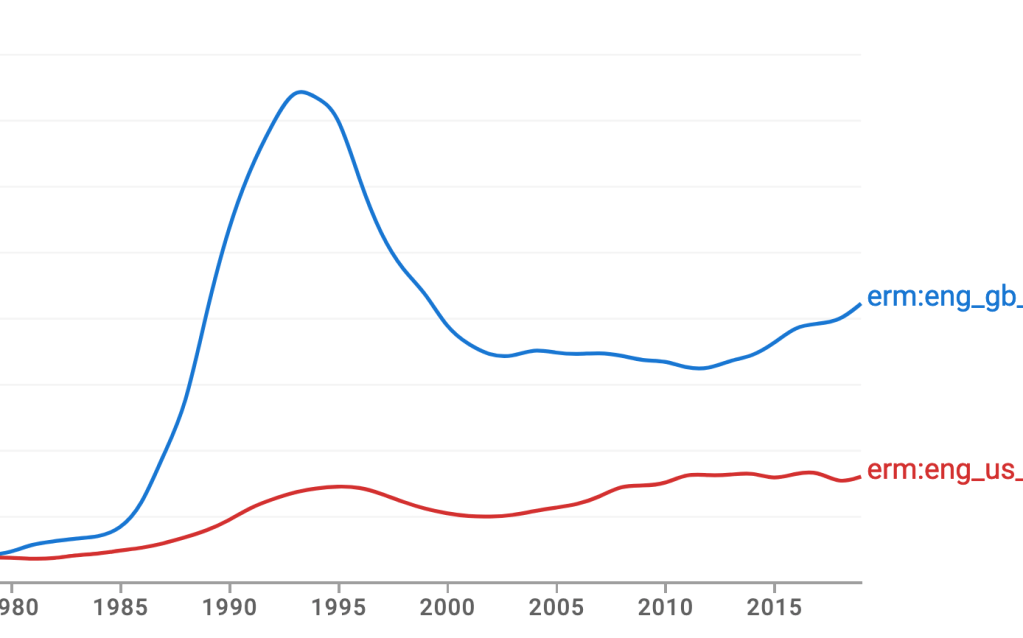

But linguistic exchange can also be seen in a more upbeat way. This is the approach of Ben Yagoda, emeritus professor of English at the University of Delaware, in “Gobsmacked!” The trend is older and more extensive than many think. Mr Yagoda describes Britishisms like “it’s early days” and “gone missing” taking hold in America almost entirely below the radar in the 1980s and 2000s, respectively.

Mr Yagoda identifies the intensifier “awfully” (as in “awfully tired”) as the first Britishism, having been noticed (disapprovingly) by an American commentator in the 19th century. The early 20th century saw many more Britishisms take hold, especially via military contact: “gadget”, “cushy”, “scrounge”, “bonkers”, “dicey” and “shambolic” all made their way from the British Tommy to G.I. Joe, and thence to the wider American public.

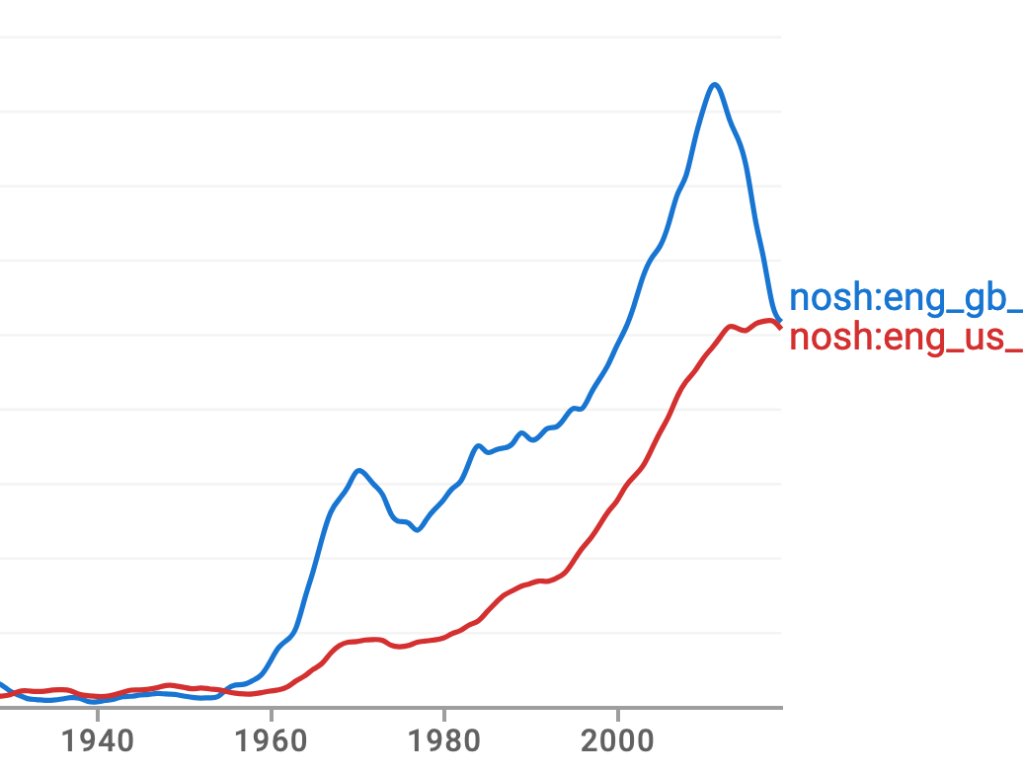

The internet has spread English in both directions. Being able to read the Guardian and to binge “The Crown” on Netflix has probably speeded up the passage of British terms into American speech. Mr Yagoda has compiled a “top 40”, including “brilliant” (merely “OK, good”), “chat up” and “ginger”. Each term gets a rating on a five-notch adoption scale, from “outpacing” (signifying Americans now use the term more than its coiners in Britain do) to merely “on the radar”, meaning only a few newspaper columnists are using it.

American Anglophiles tend to be part of a media elite who holiday in Europe (and might even use “holiday” as a verb), whereas American slang is seen as passing to Britain through less rarefied channels. Lynne Murphy, a linguist at the University of Sussex, notes that “Friends”, an American comedy show, is often blamed wrongly for the rise of “Can I get…?” at coffee shops in Britain. In her study of online lists explaining British terms to Americans and vice versa, she found the ones about Britishisms for Americans were often framed positively (for example, “a guide to the best Britishisms”), whereas for Brits Americanisms were more often negative (“41 things the Americans say wrong”).

Which Britishisms tickle American fancies? A few sounds recur, such as adjectives ending in “y”, from “cushy” and “smarmy”—Britishisms but no longer seen as such in America—to more recent ones like “cheeky” and “dodgy”. B- and p-sounds also feature, including in made-up words (“bumbershoot” is not, as some Americans believe, a British word for an umbrella). The Oatmeal, a web comic, summed up how British English sounds to Americans: “I remember my days at Oxford, we’d often dabble in a little rumpy-pumpy before dingbangling a fresh todger, haha!” That hints at another source of Britishisms making their way west: insults and “naughty bits” like “shag” and “wanker”. A spirit of playfulness pervades Americans’ use of these British words; they may even tend to overuse them and underestimate their rudeness, because the sounds are so silly.

It is possible that the British need “Gobsmacked!” more than their American cousins. The Americanisation of British English is well known; the Britishisation of American English, not so much (as a Californian teen might say). A country not sure what influence it still has in the world might like to know that the superpower across the ocean still fancies the mother country and its culture. ■