I’ve written several about “kit” as equipment or gear, most recently here. Lately, the California-based bicycle equipment company Thousand has been putting this ad(vert) in my Facebook timeline.

I’ve written several about “kit” as equipment or gear, most recently here. Lately, the California-based bicycle equipment company Thousand has been putting this ad(vert) in my Facebook timeline.

Last month on National Public Radio, longtime Los Angeles Times columnist Patt Morrison said about a venerable L.A. drive-in movie: “You can get up to some romantic hanky panky if you want. Or you can have the kids asleep in the back seat.”

A couple of years ago, Tim Hererra, or the New York Times Smarter Living newsletter, had this signoff at the end of an entry on what to do with a day off: “Tweet me … and let me know what you get up to, and have a great week!”

They were both using the expression “get up to” in the sense of this OED definition: “to become engaged in or bent on (an activity, esp. of a reprehensible nature).” The dictionary’s first citation is from an 1864 book: “And you know, when people do get up to mischief on the sly, punishment is sure to follow.” That and the next four cites are British, the most recent being Kingsley Amis’s The Old Devils (1986): “As anyone might who was as keen as he on what you could get up to indoors.” The sixth and final quote is from an anonymous 2009 article in the American magazine Wired.

I can’t resist one more example, from a 2021 New York Times obituary of the Montreal-born photographer Marcus Leatherdale, who lived on the Lower East Side of New York in the late 1970s:

The Grand Street loft was an unusual household. [His wife Chloe] Summers was a dominatrix working under the name Mistress Juliette; one of her clients cleaned the place free of charge. [Robert] Mapplethorpe assisted Ms. Summers with her work by offering her a pair of leather pants, a rubber garter belt and S&M tips. Mr. Leatherdale, sober, tidy and decidedly not hard core despite his leather uniform, was mock-annoyed one morning when he awoke to find an English muffin speared to the kitchen table with one of Ms. Summers’ stilettos. “What did you get up to last night?” he asked her.

The OED and Google Books Ngram Viewer agree that this was originally a British expression. The apparent recent American adoption isn’t surprising, given that we’ve long similarly used “up to” without the “get,” for example, “He was up to no good.” For now I’m labeling it “on the radar.”

Fateful Faithful reader Stuart Semmel emailed that he had just heard an American reporter use the verb “hoovering” on National Public Radio. As it happened, I had also heard Bobby Allyn, talking about Elon Musk’s recent decision to limit the number of tweets individuals can see: “Musk says this is all about artificial intelligence companies, right? They train AI models, as we know, by hoovering up tons of data from websites like Twitter.” (Almost predictably, Allyn used the now near-mandatory Zuck-talk “right?”)

I’ve written several times about “hoover,” derived from the vacuum company, often (but not always) followed by “up,” and meaning, according to the OED, “To consume or take in voraciously; to devour completely.” But when I Googled the word before answering Stuart, I found almost the entire first screen’s worth of results had to do with a meaning I was unaware of. It’s not in the OED or Green’s Dictionary of Slang, but an Urban Dictionary post from 2010 has it as one of nine (count ’em, nine) “hoover” definitions:

v. colloquial Being manipulated back into a relationship with threats of suicide, self-harm, or threats of false criminal accusations. Relationship manipulation often associated with individuals suffering from personality disorders like Borderline Personality Disorder or Narcissistic Personality Disorder.

The next example I could find was in the title of a 2017 book by (American) Amber Ault: Hoovering: How to Resist the Pull of a Toxic Relationship & Recover Your Freedom Now. And the word seems to be very much still out there, as witness 2022 articles in Psychology Today and Bustle. Those are both American publications, which leads me to suspect that psychological hoovering is an American coinage. But I’m not sure and would be interested in evidence either way.

Fifteen years ago, Lynne Murphy wrote a blog post about the use of “dead” as an adverb in British English. She posted this photo of a sign she encountered in the village of Hythe:

And she gave two example she had found online. The first was from a comment on blog.pinknews.co.uk: “Dom looks dead sexy in eyeliner and black nail varnish.” (“Nail varnish” is BrE for “nail polish.”) The second were some excerpts from the blog of a band called MJ Hibbett & the Validators, describing a holiday in Singapore (capital letters in the original):

… I also watched “Sky High”, which was dead good. […] It’s odd really, some of it is DEAD POSH, like the lobby and the millions of people tidying plates away at breakfast, and some of it ISN’T, like the mucky marks on the walls and the water dripping on your head in reception. […] We then had a LOVELY bit of tapas (ooh, it was DEAD nice, roast potatoes and hot garlicy [sic] tomato sauce, ACE!)

Someone commented on the post: “My brother and his friend had rescued a rabbit from somewhere out on the farm and were enthusiastically telling us how well it was doing: ‘It’s dead alive, you know.'”

Lynne puckishly observed that the usage — “dead” as an adverb meaning “very” — is “dead British.” She’s right, though adverbial “dead” does show up in a small number of phrases that are familiar in America as well (I assume) as in Britain: “dead wrong,” “dead right,” “dead against,” “dead tired,” “dead drunk.” (The last two share the sense of the quality being so pronounced that the person having it appears dead, or close to it. Green’s Dictionary of Slang suggests that the adverbial form actually entered the language through “dead drunk,” which shows up in the 1600s and has been in common use ever since.) Dan Jenkins published a novel in 1974 called Dead Solid Perfect. And commenters on Lynne’s post noted that in boating contexts even in the U.S., “Dead Slow” is a familiar formulation.

Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries makes a useful distinction: the phrases that are common in the U.S. all use “dead” to mean “completely.” But only Britain is it also frequently used to mean “very.” The examples given by the dictionary, none of which are common in America, are:

But hold on a second. What got me thinking about this was noticing American uses of the first one, “dead easy.” The phrase has shown up fifty-two times in the New York Times, all since 1996, and no fewer than five of them, including the most recent, from the pen of NOOBs legend Sam Sifton. In the piece linked to, Sifton is saying that a noodle dish is “dead easy to make,” and a substantial majority of the Times uses describe a recipe or cooking technique. (A number of the early ones have an interesting variation, including the 1996 article, which says the cook’s trick of using bottled salad dressing in preparing a dish is “is drop-dead easy, and it tastes good.”)

But hold on another second and look at the Google Books Ngram Viewer graph for American and British uses of “dead easy”:

My investigation on the Google Books database supports American origin of the phrase, specifically in a frontier, Western, or slangy context. In 1889, a Salt Lake City newspaper, the Deseret News, had the line, “It’s dead easy, see.” In Life magazine in 1896, there was this line of dialogue followed by a parenthetical comment. “‘You must get into the brainy set. Then it’s dead easy.’ (His language is so droll.)” It’s not “dead easy,” but Green’s Dictionary of Slang quotes an 1899 line from American humorist George Ade’s Fables in Slang: “She was going to be Benevolent and be Dead Swell at the Same Time.”

I’m sure there must be some, but off the top of my head I can’t think of any other examples of an American expression that fell by the wayside in the U.S., got taken up by the British, and then, more than half a century later, became a NOOB.

Some months back, my daughter Maria Yagoda alerted me to a vogue word she’d encountered in the food-and-drink world, which she thought was a Britishism: “bubbles,” as a synecdoche (part signifying the whole) for Champagne or more broadly sparkling wine. I took a stab at researching it but was defeated by the sheer abundance of uses of the word in all sorts of context, including non-synecdochical wine discussions. (E.g., “I love Champagne because of the bubbles.”)

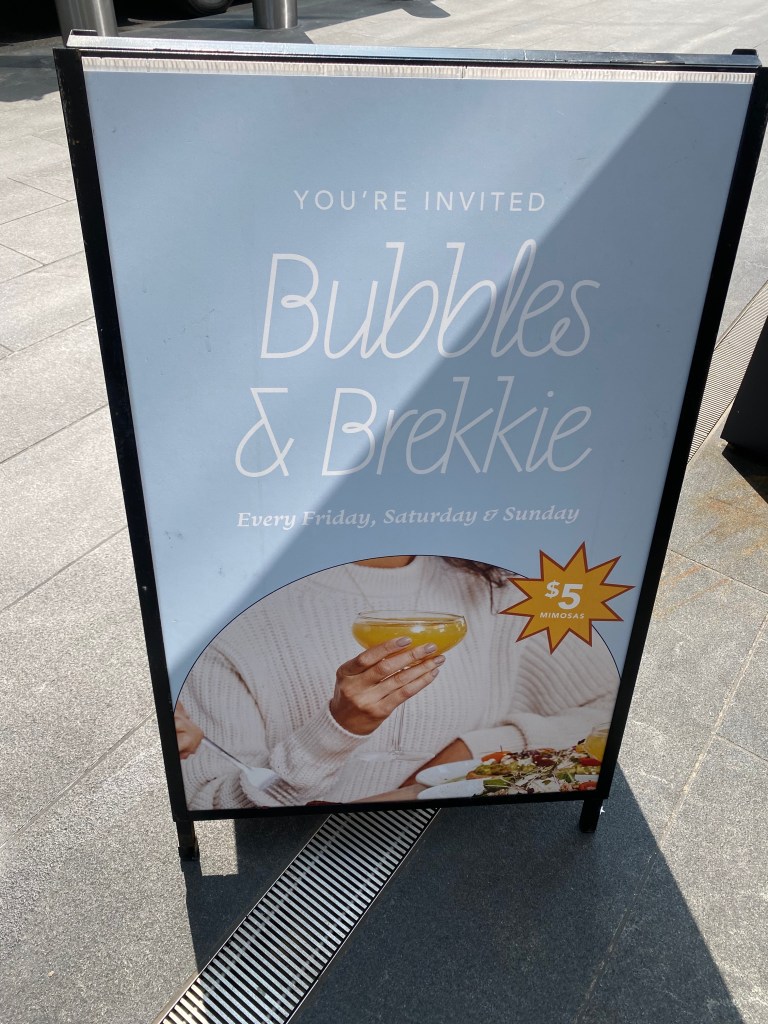

But then I was walking in Manhattan and came upon this two-sided sign:

So, not only “bubbles” but also “brekkie” and “mate“: a veritable NOOBs-orama! My enthusiasm was dampened a little bit when I found out that the advertised enterprise, Bluestone Lane, was founded by a former Australian Rules Football player named Nick Stone and describes itself as “bringing Aussie café culture (and better coffee) to the USA.” Clearly, the signage is leaning in to the Aussie identity.

In any case, the Bluestone sign inspired me to research the issue. I found, not surprisingly, that the more common term in both Britain and the U.S. has always been “bubbly.” (That isn’t synecdoche but rather a nominalized adjective. I”ll also note that in hip-hop, the preferred term has been “bub.”) According to Green’s Dictionary of Slang, “bubbles”=sparkling wine actually first occurs in a 1945 American dictionary of criminal slang. But that appears to be a bit of an anomaly, as the next example I have, from the OED, is from a 1989 Brisbane, Australia, newspaper article: “The 1986 pinot chardonnay bubbles..will cost about $22 in the bottleshop,..close to the lower-priced French champagnes.” That might be an outlier, too, as the next cite (from Green’s) doesn’t come till 2010, in a South Africa newspaper: “Sip a glass of seriously posh bubbles.” The term had reached Britain by 2018, when a novel had this line of dialogue: “’I’m going to have some more bubbles; do you want a glass?’”

By that time, “bubbles” had arrived in America. The OED quotes a line from a 2017 romance novel by K.A. Linde: “We need ice cream and bubbles to celebrate.” And an undated article by an American wine writer has the line, “You should also know that the French government has strict rules for Champagne makers… and if they don’t comply, they can’t call their bubbles ‘Champagne’ either.”

Clearly, I don’t have an abundance of data. But the evidence would suggest that “bubbles” had emerged in South Africa and possibly Australia by 2010 and subsequently spread to the U.K and then, fairly quickly, to the U.S.

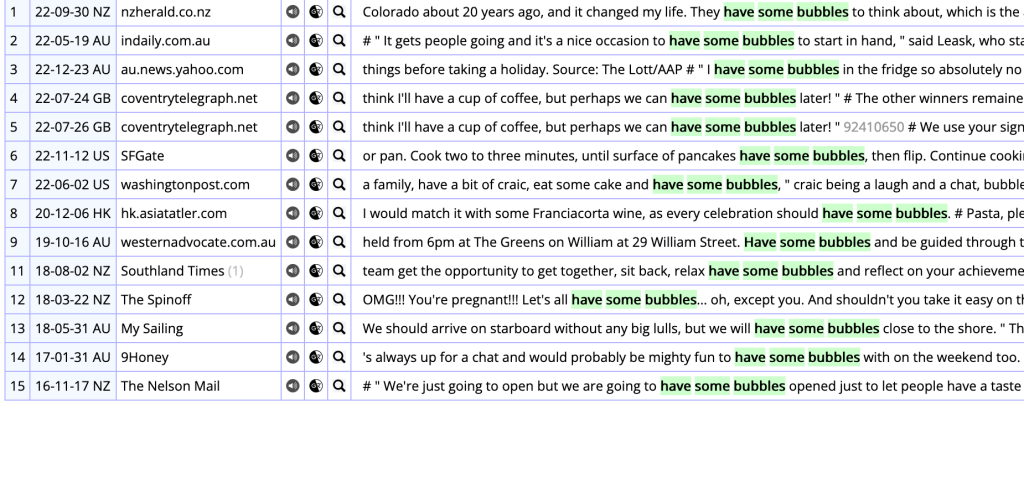

Update: After getting some blowback in the comments along the lines of “I’ve been British all my life and I’ve never heard of such a thing,” I decided to investigate further by searching for “have some bubbles” in a few recent corpora. News on the Web (NOW), which tracks usage from 2010 to the present and has some 17.5 billion words of data, had thirteen hits. (There are fifteen in the graphic below, but numbers 4 and 5 are the same, and 13 refers to the bubbles in pancakes.)

The nationalities are six from Australia, four from New Zealand, one from the U.K, one from Hong Kong, and one from the United States — but that really doesn’t count since it’s in a quote from someone from Northern Ireland, and the reporter defines both “bubbles” and “craic” (a laugh).

And that’s where we’ll have to leave it for now.

This appeared on my New York Times app this morning:

I previously discussed “shock” as adjective here.

“So who should be most brassed off by this show?”–Jason Farago, New York Times, June 1, 2023, in reference to “It’s Pablo-Matic,” an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, which he did not like.

When I came to the phrase I’ve put in italics, it sounded like a Britishism, and it is. Green’s Dictionary of Slang defines it as “irritated, fed up, annoyed,” and has two 1940 citations, one from a book called A. A. S. F. (Advanced Air Striking Force, by Charles Gardner: “Cobber said he was ‘brassed-off,’ especially after he had got half-way home once, only to be called back to hand over his flight and teach two new-comers the way around.” Neither Green’s nor the OED has anything to say about etymology, but it would appear to be a combination of the verb “brass off,” meaning to complain, which is seen in British service slang as early as 1925 and “browned off,” meaning annoyed, which popped up no later than 1931.

Observers at the time had some fun describing the differences among those two phrases and another new one, “cheesed off.” A 1943 Time magazine article on RAF slang reported: “Among thousands of Americans, ‘browned off’ already means fed up. (‘Brassed off’ means very fed up and ‘cheesed off’ is utterly disgusted.)”

And a 1943 book called Women at War had these index entries:

“Brassed Off. See Browned Off.

“Browned Off. See Cheesed Off.

“Cheesed Off. See Brassed Off.”

In Britain, “brassed off” got pretty popular pretty fast. A short story by Herbert Bates which was published in a 1942 book has this passage:

He spent most of the rest of his life being brassed off.

“Good morning , Dibden, ” you would say. “How goes it?”

“Pretty much brassed off, old boy.”

“Oh, what’s wrong?”

“Just brassed off, that’s all. Just brassed off.”

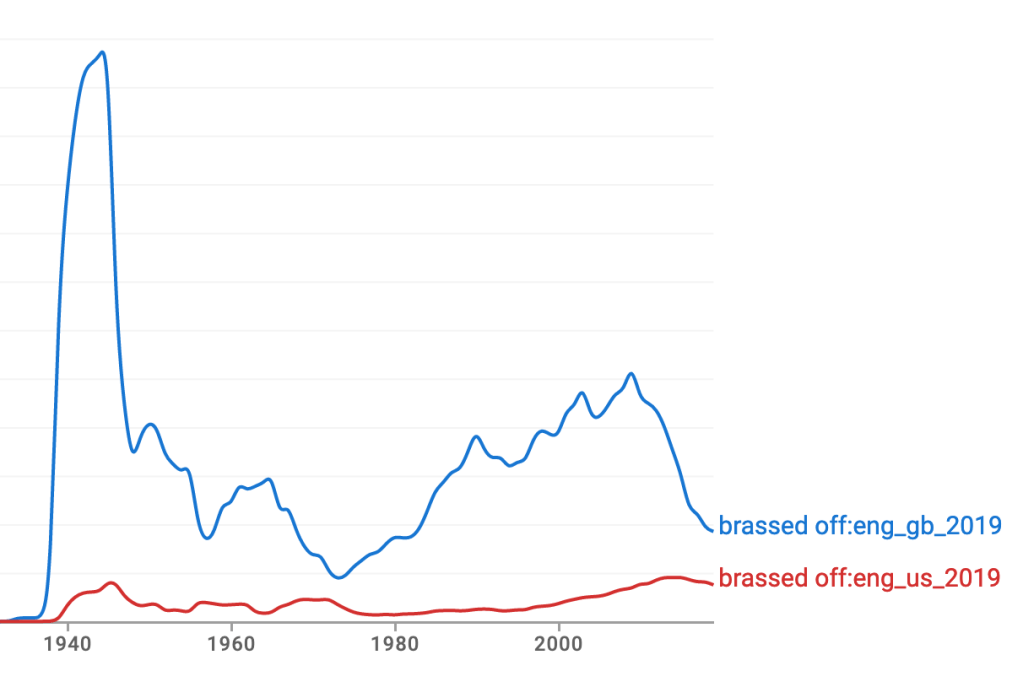

In Britain, the phrase fell off in popularity after the War, but started picking up again in the 1980s, as this Ngram Viewer chart shows:

In 2004, the BBC ran a TV series called Brassed Off Britain, which endeavored to identify the things the country found most annoying. (Junk mail “won,” followed closely by banks and call centres.)

But the phrase has never taken hold in America. Until the line from Jason Farago quoted above, it had never been used in the New York Times by an American writer or source, except in reference to Brassed Off, described by the Times as “a funny and poignant [1997] film set in a bleak Yorkshire mining town.” Similarly, it does not show up at all in the Corpus of American Historical English or from any American sources in News on the Web (NOW), a corpus of more than 17 billion words published since 2010.

So well done, Jason Farago! You have perpetrated a true One-Off Britishism.

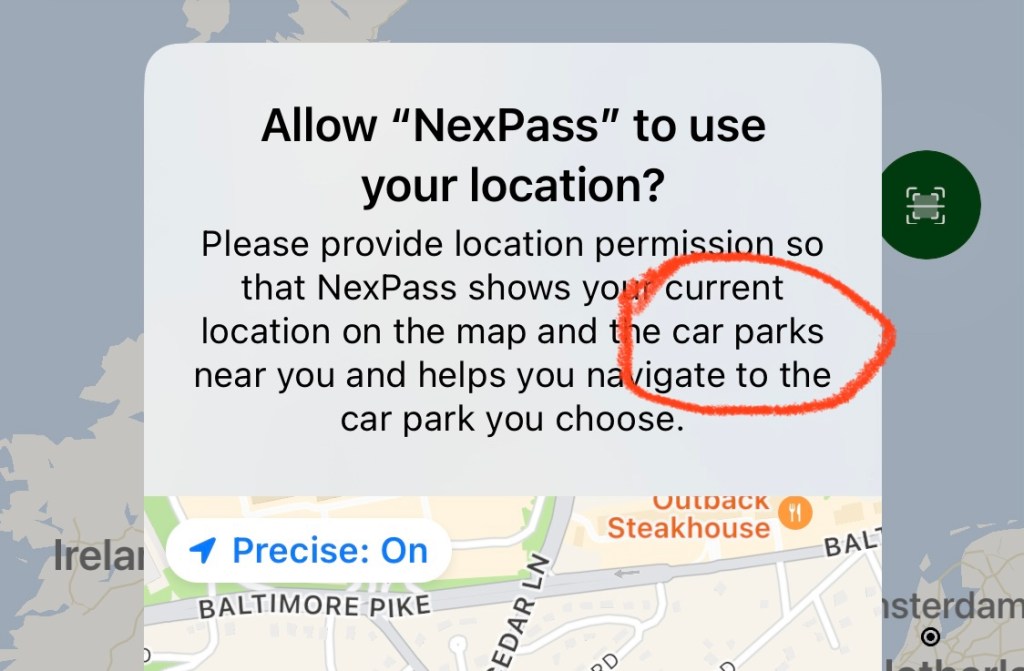

As previously noted, Americans say “parking garage” for a building and “parking lot” for an on-the-ground parking facility, but the British “car park” is occasionally found here. (Commenters suggested that Grand Theft Auto, whose script apparently uses it, might have been an influence.)

The term popped up just today when I downloaded an app from a New Jersey real estate and parking company, Nexus Properties:

Ben Zimmer, language columnist for the Wall Street Journal, messaged me the other day:

Are you watching “Succession”? And if so, are you noticing occasional Britishisms sneaking through from the British writers on the show? Tom says “could do” (periphrastic “do”!) talking to Shiv in “Living+,” and Shiv says “Sorry to break up the brains trust” (instead of “brain trust”) in “Tailgate Party.” Of course, Matthew MacFadyen is British and Sarah Snook is Australian, so it’s possible the actors themselves tweaked the lines. Someone also pointed out that “sex pest” was used in a Season 2 episode (by Kendall, I think).

I am perhaps the only person I know who is not watching Succession, so all this was new to me. I had never actually heard of “sex pest,” but just a few days later, someone wrote to the American Dialect Society listserv about a headline on the Jezebel website: “Lauren Boebert Filed for Divorce, and Her Sex Pest Husband Didn’t Take It Well.” None other than Ben Zimmer replied: “‘Sex pest’ is a popular in British tabloid headlines for, e.g., allegations against Prince Andrew. ‘Sex pest’ is actually a useful term, since it implies something a bit less extreme than, say, ‘sexual predator.'”

The OED ‘s definition: “a sex offender; a person who sexually harasses another.” The first citation is what appears to be a headline from The Times in 1985: “Sex pest’s one-way ticket back. A convicted sex offender, sent by a Californian judge..to Florida,..is to be returned to where he came from.”

The phrase has appeared in the New York Times eight times since 1991. They have mostly been in British contexts, including a reference to a report on predatory behavior of Jimmy Savile which said “it appeared to be an ‘open secret’ that Mr. Savile was a ‘sex pest.'” However, that 1991 example was from a humorous essay by American writer Elinor Lipman about the guy at work who “sniffs a woman’s hair at the copy machine and asks what kind of shampoo she uses.” The title was, “Are You the Office Sex Pest?”

In 2020, reviewing Curtis Sittenfield’s novel Rodham, book critic Dwight Garner, a NOOBs icon, wrote, “The portrait of Bill Clinton as sex pest in this novel is dark, and grows darker.” And in 2021, the Times reported on an SNL skit in which a talk-show host introduced Rep. Matt Goetz (played by Pete Davidson) this way: “As we’d say in the early 2000s a hot mess and as we’d say today, a full-on sex pest.”

On her blog, Fritinancy, Nancy Friedman has chosen as the Word of the Week “perk-cession,” defined (by the Wall Street Journal) as the way “companies are cutting back on prized employee perks from fancy coffee to free cab rides as they vow to trim costs and prioritize efficiency.” She writes:

Perk, by the way, is a truncation of perquisite, which entered English from Latin—“a thing acquired or granted”—in the 1400s. Since around 1567, perquisite has meant “any casual profit, fee, remuneration, etc., attached to an office or position in addition to the normal salary or revenue,” as the OED puts it. The “perk” abbreviation started appearing in truncated form around 1869 in the UK. I’ve been trying unsuccessfully to determine when it migrated to the US; I’m pretty sure it was within my own lifetime. (When I started working, I would have used the term “fringe benefit” rather than “perk.”) Anyone out there able to trace perk’s procession?

OK, OK, I’ll do it.

Nancy specified 1869 because that’s the date of the first citation in the OED, from a muckraking book by James Greenwood called The Seven Curses of London. In a chapter on thieves he writes about a species of “small pilfering”:

Ordinarily it is called by the cant name of “perks,” which is a convenient abbreviation of the word “perquisites,” and in the hands of the users of it, it shows itself a word of amazing flexibility. It applies to such unconsidered trifles as wax candle ends, and may be stretched so as to cover the larcenous abstraction by our man-servant of forgotten coats and vests. As has been lately exposed in the newspapers, it is not a rare occurrence for your butler or your cook to conspire with the roguish tradesman, the latter being permitted to charge “his own prices,” on condition that when the monthly bill is paid, the first robber hands over to the second two-shillings or half-a-crown in the pound.

But by 1887 the word had lost its nefarious connotation, the Pall Mall Gazette referring that year to “an order that free blacking is no longer to be among the ‘perks’ of Government office-keepers.”

As for Nancy’s question about precisely when “perk” migrated to the U.S., Green’s Dictionary of Slang has an 1882 quotation from the National Police Gazette, published in New York: “Detectives must have some protection and privileges […] not to mention the ‘perks’.” But I’ve got to think that’s an outlier, written by a British correspondent for the magazine. Myinitial research suggests the abbreviation arrived here about 1970, which is indeed (I don’t think she’ll mind me saying) within her lifetime. The first use in the New York Times came that year, in Phil Dougherty’s long-running column on advertising, the quotation marks and the explanation suggesting his readers wouldn’t be familiar with the word: “For such men as Mr. Norins and Mr. Kershaw, the cost of commuting is a perquisite— ‘perk’ in Madison Avenue jargon—bestowed by grateful management.”

Google Ngram Viewer shows British use perking up (sorry) in the 1970s and ’80s, followed by American in the ’80s and ’90s (I searched for “a perk” to limit other senses of the word.) It was used roughly equally in both countries in the 2000s, and since about 2013 it’s been more common in the U.S.