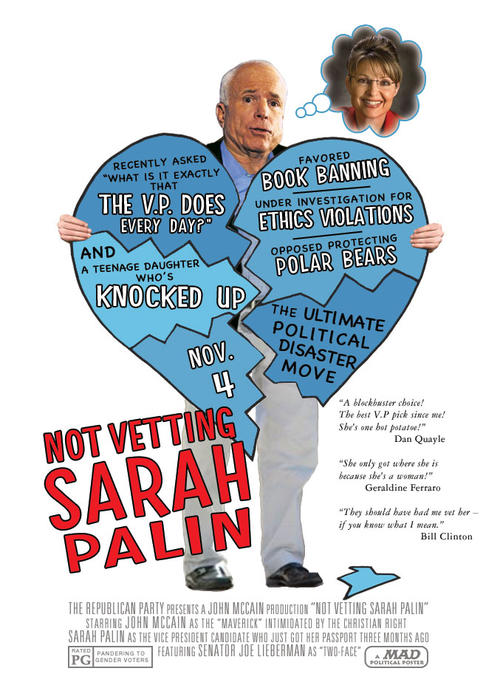

Verb, transitive. OED gives its first use as 1906 (in a Rudyard Kipling story), and defines it as, “To examine carefully and critically for deficiencies or errors; spec. to investigate the suitability of (a person) for a post that requires loyalty and trustworthiness.” It is so common now, and used in so many different contexts, that it probably doesn’t seem like a Britishism. But it is: a Google Ngram (for “vetting” and “vetted”) shows it starting to become popular in British English in the 1930s and peaking around 1990–exactly the same time, according to an Ngram for American English, that it started to take off in the U.S. Currently, it’s roughly equally popular on both sides of the ocean.

“If I was on a matchmaking site, I would want to know that the people they are going to hook me up with had at least been vetted.” (The Desert Sun, May 8, 2011)/Vetting for [Zoe] Baird’s appointment began at once. Exactly what her position might be was left unclear; the vetting team was simply told that it would be something important. (Sidney Blumenthal, The New Yorker, February 15, 1993)

Verb, transitive or intransitive. The OED’s definition:

Verb, transitive or intransitive. The OED’s definition:

In the UK, one disposes of unwanted stuff in the rubbish bin or merely the bin. The venerable U.S. equivalents are garbage can and trash can. In the April 18, 2011, edition of (yes) the New Yorker, one finds this in (American) Evan Osnos’s

In the UK, one disposes of unwanted stuff in the rubbish bin or merely the bin. The venerable U.S. equivalents are garbage can and trash can. In the April 18, 2011, edition of (yes) the New Yorker, one finds this in (American) Evan Osnos’s