This noun phrase meaning “expert” (usually followed by at, as in “a dab hand at cookery“) derived from the now-archaic dab, meaning the same thing, which is “frequently referred to as school slang,” according to the OED. The first citation is from The Athenian Mercury in 1691: “[Love is] such a Dab at his Bow and Arrows.”

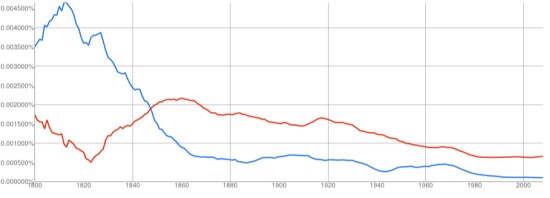

Dab hand apparently originated as Yorkshire dialect pre-1800, but didn’t become widely used in Britain until the 1950s, according to a Google Ngram. Following a familiar pattern, it peaked in Britain in about 1990, while U.S. use continues to rapidly increase (though it’s still used less than half as often here as there).

There are many dab American hands nowadays. The distinguished Stanford Berkeley linguist Geoffrey Nunberg was quoted in the New York Times in 2011 as follows: “I fancy myself a dab hand at Google, but it drives me crazy,” but the term shows up in less elevated company as well:

“Hughes graduated in May with a degree in entrepreneurship management from Boise State University. Now he’s putting what he learned to work as he functions as a driver, a furniture mover, and at times a dab hand with the little wrenches IKEA encloses in its packaging (his business offers assembly).”–Idaho Business Review, August 22, 2012

“[‘Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter’ director Timur] Bekmambetov, who proved himself a dab hand at vampire thrillers (‘Night Watch,’ ‘Day Watch’) before he directed the 2008 graphic-novel adaptation ‘Wanted,’ handles the violence in an arresting if flashily impersonal style.”–Variety, June 22, 2012

“At Virginia Polytechnic, [architect Kimberly Peck] started playing around with industrial design, and became a dab hand at using the lathe, the milling machine and other mechanical equipment.”–New York Times, April 15, 2012