A syndicated columnist called The Word Guy (TWG) recently wrote the following:

A network-news correspondent recently described a medical issue that has led doctors and researchers to a “worrying conclusion.” Now, I’ve never seen a conclusion worry. I’m wondering whether it knits its brow, rubs its head, and grits its teeth.

More and more people are using “worrying” not to mean “fretting” (“a worrying mom”) but “causing fretting” (“a worrying event”). “Worrying” joins other participles that have recently flipped in meaning, e.g., “these problems are very concerning.”… Frankly, I’m worrying about these worrying trends.

I have the same impression as TWG that concerning and worrying are on the rise as adjectives. And, indeed, Google News searches for each pull up examples on the first screen:

- “The Mystery of Andros Townsend’s Slump Is Worrying for England and Spurs” (headline from Bleacher Report)

- “In any of those situations, it’s very concerning. Up until we get all of the facts, we will let the process run its course.”—General Manager of the Baltimore Ravens Ozzie Newsome, on the arrest of the team’s player Ray Rice (ESPN.com)

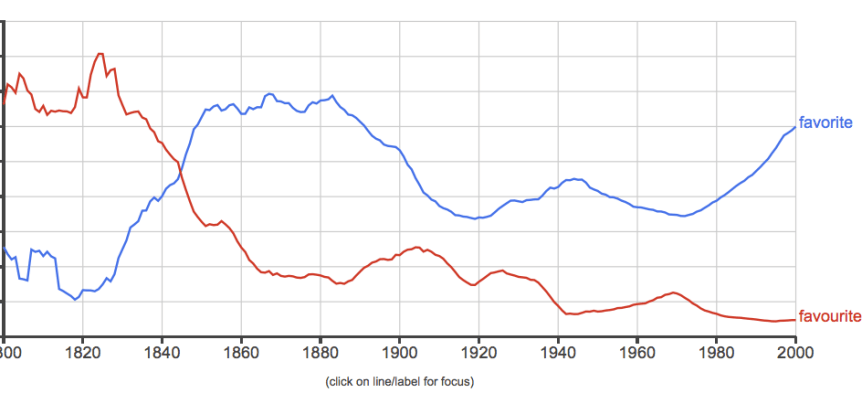

To my mind, the conventionally “correct” alternative to both would be either troubling or worrisome. Google Ngram Viewer (showing the relative frequency of each term in printed English sources) gives some surprising results. (I put the word very in front of each word so as to get only adjectival uses.)

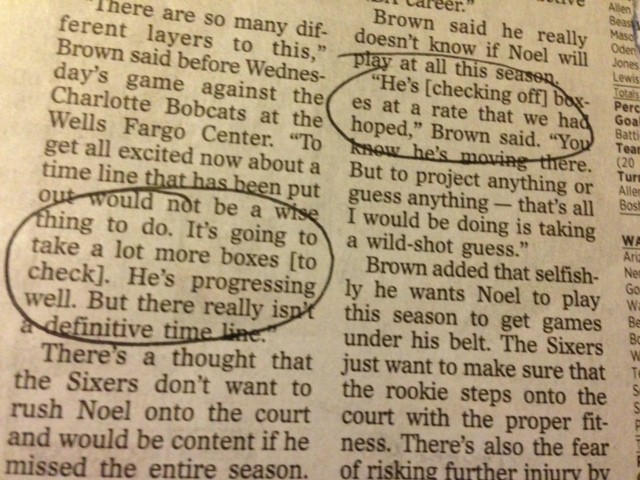

I was struck by the relatively recent ascendance of troubling and worrisome, but the big surprise was the relatively long tail of worrying. When I told Ngram Viewer to search only in British books, here’s what I got:

A NOOB, a palpable NOOB!

The OED shows, not surprisingly, that both words TWG found problematic have been used as adjectives for a long time. We find worrying (as well as figurative literally!) in Frederick Reynolds’s Life & Times (1826), “Your whole conduct is literally worrying and annoying in the extreme,” and concerning in Coleridge’s Literary Remains (1839): “To utter all my meditations on this most concerning point!”

Beyond historical precedent, TWG’s objections are specious. If he thought about it for a minute, he would realize that he had indeed seen a conclusion worry, e.g., “The researcher’s conclusion worried his collaborators.” Indeed, it is customary, when a person, situation, or thing emotionally verbs someone, to describe that person, situation, or thing as verbing. Think of perplexing, frightening, amusing, touching, exciting, etc. The only counter-examples that come immediately to mind are scary and awesome. The varied usefulness of worry is probably what led to the delayed arrival of worrying the adjective, just as the prominence of concerning in the sense of “having to do with” delayed that new meaning.

In any case, whether you find it concerning or not, it seems clear that these adjectives are here to stay