Humility is always a good thing. I got a dose of it recently, courtesy of a BuzzFeed article posted to Facebook by a friend of mine, Siobhan Wagner, a journalist who was born in the U.S, but has been living in London for nine years. The article was called “Americans On Tumblr Are Trying To Find Out What A ‘Cheeky Nando’s’ Is And Are Struggling” and concerned a meme that had become popular in England. Here’s an example:

As the title suggests, the article detailed the exasperation expressed by Americans, in trying to cypher out the meaning not only of “cheeky Nando’s” but of the definitions for it put forward by Brits. Here’s one exchange:

And another:

I mentioned humility. The notion is relevant because premise of this blog is that the gap between the two brands of English — American and British —is diminishing and will one day recede to nothing.

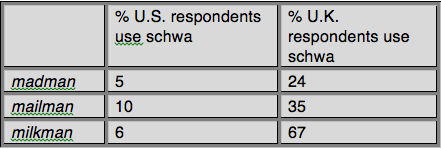

The cheeky Nando’s discourse showed me how far away that day is. Both the above explanations could be in a foreign language, so full are they with slang that a Yank can barely comprehend, much less consider utilizing. Take the second one. We get “mate,” to be sure; “wif” is a rendition of Mockney th-fronting (as in calling Keith Richards “Keef”). “jd”: I have no clue. Same with “curry club” and “the ‘Spoons.” Urban Dictionary has this for “ledge”: “Shortened slang for ‘legendary’, or, more commonly, for ‘legend’.” Then there’s this whole “banter” thing, which seems to elevate joking around with the lads to a sacred pedestal. (I love the #barackobanter hashtag.) Turning again to Urban Dictionary, I find the brev defined as “chav word for brother,” i.e, it’s a case of th-fronting abbreviation. And note that the person giving the definition calls him- or herself “chavvesty.” The OED, which doesn’t include ledge or brev, defines chav this way: “In the United Kingdom (originally the south of England): a young person of a type characterized by brash and loutish behaviour and the wearing of designer-style clothes (esp. sportswear); usually with connotations of a low social status.” (Sportswear??) I can figure out “Top. Let’s smash it” from context clues, but I couldn’t imagine using it.

That still doesn’t explain “cheeky Nando’s”! I have actually written about cheeky, which is something like a cross between sassy and impudent. And I know from my time in the U.K. that Nando’s is a chain of restaurants specializing in spicy grilled chicken, which has now expanded into the U.S.; I can figure out that in the meme, “Nando’s” signifies, basically, “food ordered and eaten in a Nando’s establishment.” (For a humorous take on the chain see this video.) But I still didn’t have a clue as to what the expression means. Taking on the established befuddled Yank role, I asked Siobhan if she could supply a definition/explanation, and she kindly did so:

Basically, the concept of a “cheeky Nandos” is similar to a “cheeky pint.” Maybe when you were in London, someone might have asked you ‘Fancy a cheeky pint after work?’ Effectively they’re saying: I know it’s only Tuesday and I really should be rushing home to make something for dinner or perhaps (more virtuously) going to the gym, but do you want to have a quick drink or two in the local pub before heading on the torture chamber known as the rush hour tube? A “cheeky Nandos” is, similarly, an unexpected suggestion. You’re probably already out with friends, maybe at the pub, actually maybe having that “cheeky pint” that was suggested, and then your stomach rumbles and you’re like: “Actually, how would you fancy a cheeky Nandos now?” Nandos following the consumption of 1.5-2 alcoholic beverages probably falls under the category of “cheeky.” Going to Nandos drunk isn’t cheeky, though. The idea is you are in the mid-point of your night out with friends when “banter” is really going. Everyone is laughing, probably “taking the piss” (making fun) of each other, and a relaxed sit-down restaurant where you pay up front (so you don’t have the messiness of figuring out how to split the bill later) is totally perfect.

I get it, kind of. But, keeping with the theme of humility, I’m still very ignorant on what might be called the rhetorical framing of the meme, including what it means that, in some representation, David Cameron (hardly a chav) is pictured. Can English readers help me out on the issue of exactly what group is being mocked, and what group is doing the mocking–and if there is any overlap between the two?