This phrase, “the fullness of time,” meaning, more or less, the appropriate time, was originally confined to Christian contexts. For example, in the King James Bible, Galatians 4:4 reads, “But when the fulness of the time was come, God sent forth his Son, made of a woman, made under the law.”

In due course — or in the fullness of time — the expression began to universally take the form “in the fullness of time,” meaning at the appropriate time, or after a certain amount of time, usually lengthy, has passed. The first secular use cited by the OED unsurprisingly is from Charles Dickens (Barnaby Rudge, 1841), who, as he did, brought the high-flown rhetoric down to earth: “Nor was she quite certain that she saw and heard with her own proper senses, even when the coach, in the fullness of time, stopped at the Black Lion.”

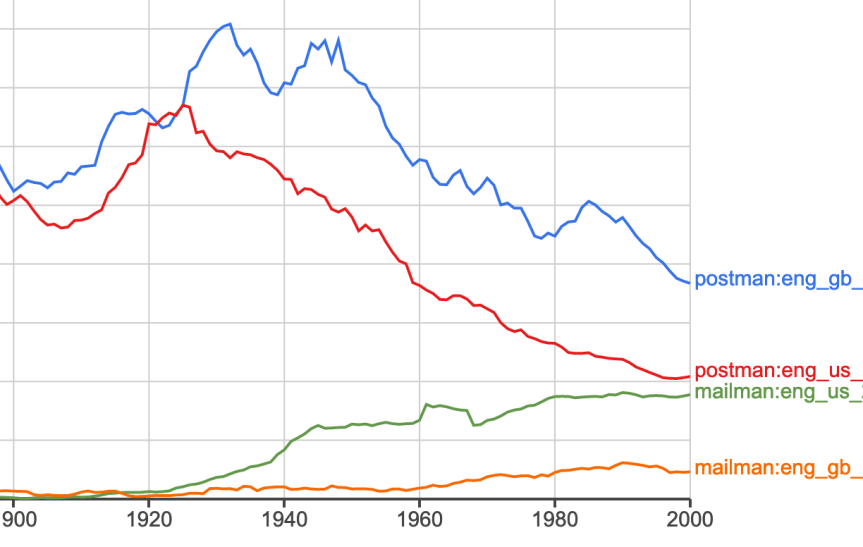

As far as transatlantic patterns go, Google Ngram Viewer shows much more frequent use in the U.S. than in Great Britain in the late nineteenth-century; I’d venture that the reason is America’s greater degree of public piety.

The phrase’s popularity shot up in Britain between 1900 and about 1945, corresponding, I’d say, to its adoption there in non-religious contexts, especially favored by windbag politicians, and those making fun of them.

But in the fullness of time (sorry, can’t help myself), America caught up. Reliable figures for Ngram Viewer only go up to 2000, but the Corpus of Global Web-Based English — a snapshot or nearly 2 billion words on online text in 2012-13 — shows nearly equal use of the phrase in the U.S. and U.K.

Since it began publishing in 1865, the New York Times has used the phrase 210 times, but 17 percent of them have been since 2010. For example, in reference to astronomical shifting, science writer Dennis Overbye observed in 2018, “In the fullness of time, everything gets everywhere.” And that same year, in a review of George Bernard Shaw’s St. Joan, theater critic Jesse Green wrote:

“What other judgment can I judge by but by my own?” Joan asks, casually assuming supremacy over churchmen and kings. From this idea comes not only the necessary sentence of a perfectly fair proceeding but also, in the fullness of time, Protestantism, nationalism, individualism and, as Shaw would have it, the Great War, which had recently concluded as he started writing the play.