Fifteen years ago, Lynne Murphy wrote a blog post about the use of “dead” as an adverb in British English. She posted this photo of a sign she encountered in the village of Hythe:

And she gave two example she had found online. The first was from a comment on blog.pinknews.co.uk: “Dom looks dead sexy in eyeliner and black nail varnish.” (“Nail varnish” is BrE for “nail polish.”) The second were some excerpts from the blog of a band called MJ Hibbett & the Validators, describing a holiday in Singapore (capital letters in the original):

… I also watched “Sky High”, which was dead good. […] It’s odd really, some of it is DEAD POSH, like the lobby and the millions of people tidying plates away at breakfast, and some of it ISN’T, like the mucky marks on the walls and the water dripping on your head in reception. […] We then had a LOVELY bit of tapas (ooh, it was DEAD nice, roast potatoes and hot garlicy [sic] tomato sauce, ACE!)

Someone commented on the post: “My brother and his friend had rescued a rabbit from somewhere out on the farm and were enthusiastically telling us how well it was doing: ‘It’s dead alive, you know.'”

Lynne puckishly observed that the usage — “dead” as an adverb meaning “very” — is “dead British.” She’s right, though adverbial “dead” does show up in a small number of phrases that are familiar in America as well (I assume) as in Britain: “dead wrong,” “dead right,” “dead against,” “dead tired,” “dead drunk.” (The last two share the sense of the quality being so pronounced that the person having it appears dead, or close to it. Green’s Dictionary of Slang suggests that the adverbial form actually entered the language through “dead drunk,” which shows up in the 1600s and has been in common use ever since.) Dan Jenkins published a novel in 1974 called Dead Solid Perfect. And commenters on Lynne’s post noted that in boating contexts even in the U.S., “Dead Slow” is a familiar formulation.

Oxford Learner’s Dictionaries makes a useful distinction: the phrases that are common in the U.S. all use “dead” to mean “completely.” But only Britain is it also frequently used to mean “very.” The examples given by the dictionary, none of which are common in America, are:

- The instructions are dead easy to follow.

- You were dead lucky to get that job.

- I was dead scared.

But hold on a second. What got me thinking about this was noticing American uses of the first one, “dead easy.” The phrase has shown up fifty-two times in the New York Times, all since 1996, and no fewer than five of them, including the most recent, from the pen of NOOBs legend Sam Sifton. In the piece linked to, Sifton is saying that a noodle dish is “dead easy to make,” and a substantial majority of the Times uses describe a recipe or cooking technique. (A number of the early ones have an interesting variation, including the 1996 article, which says the cook’s trick of using bottled salad dressing in preparing a dish is “is drop-dead easy, and it tastes good.”)

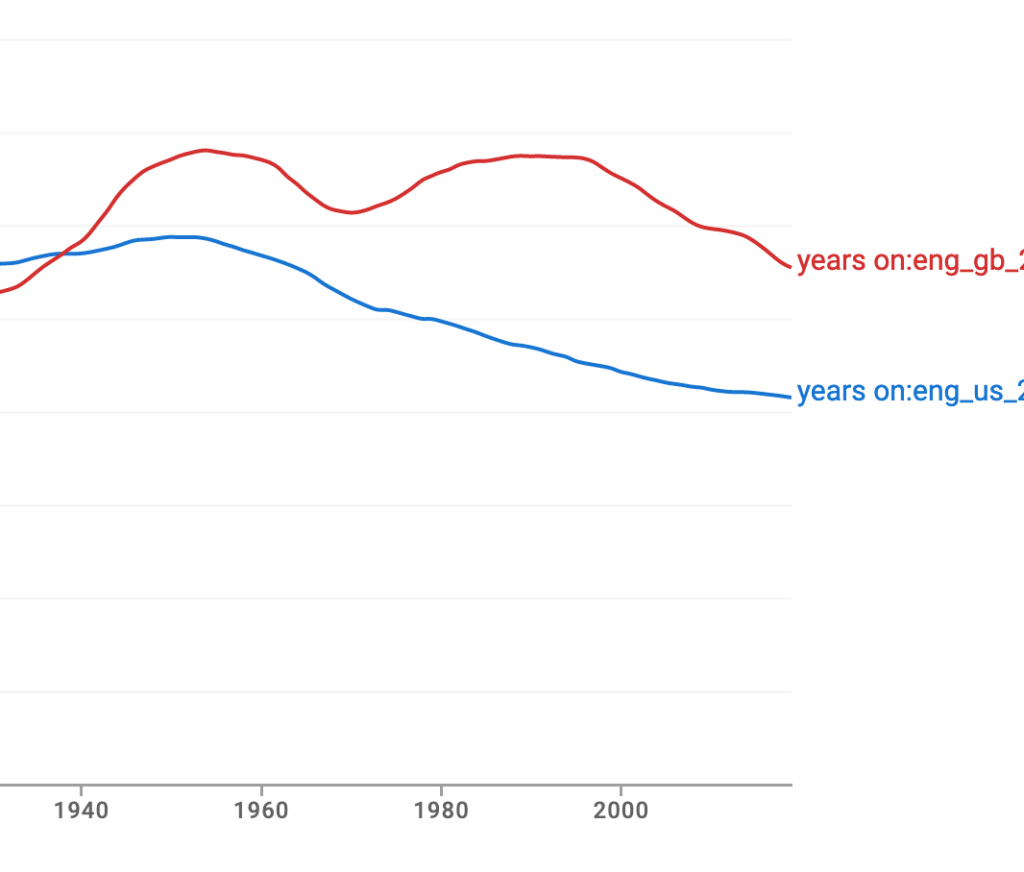

But hold on another second and look at the Google Books Ngram Viewer graph for American and British uses of “dead easy”:

My investigation on the Google Books database supports American origin of the phrase, specifically in a frontier, Western, or slangy context. In 1889, a Salt Lake City newspaper, the Deseret News, had the line, “It’s dead easy, see.” In Life magazine in 1896, there was this line of dialogue followed by a parenthetical comment. “‘You must get into the brainy set. Then it’s dead easy.’ (His language is so droll.)” It’s not “dead easy,” but Green’s Dictionary of Slang quotes an 1899 line from American humorist George Ade’s Fables in Slang: “She was going to be Benevolent and be Dead Swell at the Same Time.”

I’m sure there must be some, but off the top of my head I can’t think of any other examples of an American expression that fell by the wayside in the U.S., got taken up by the British, and then, more than half a century later, became a NOOB.