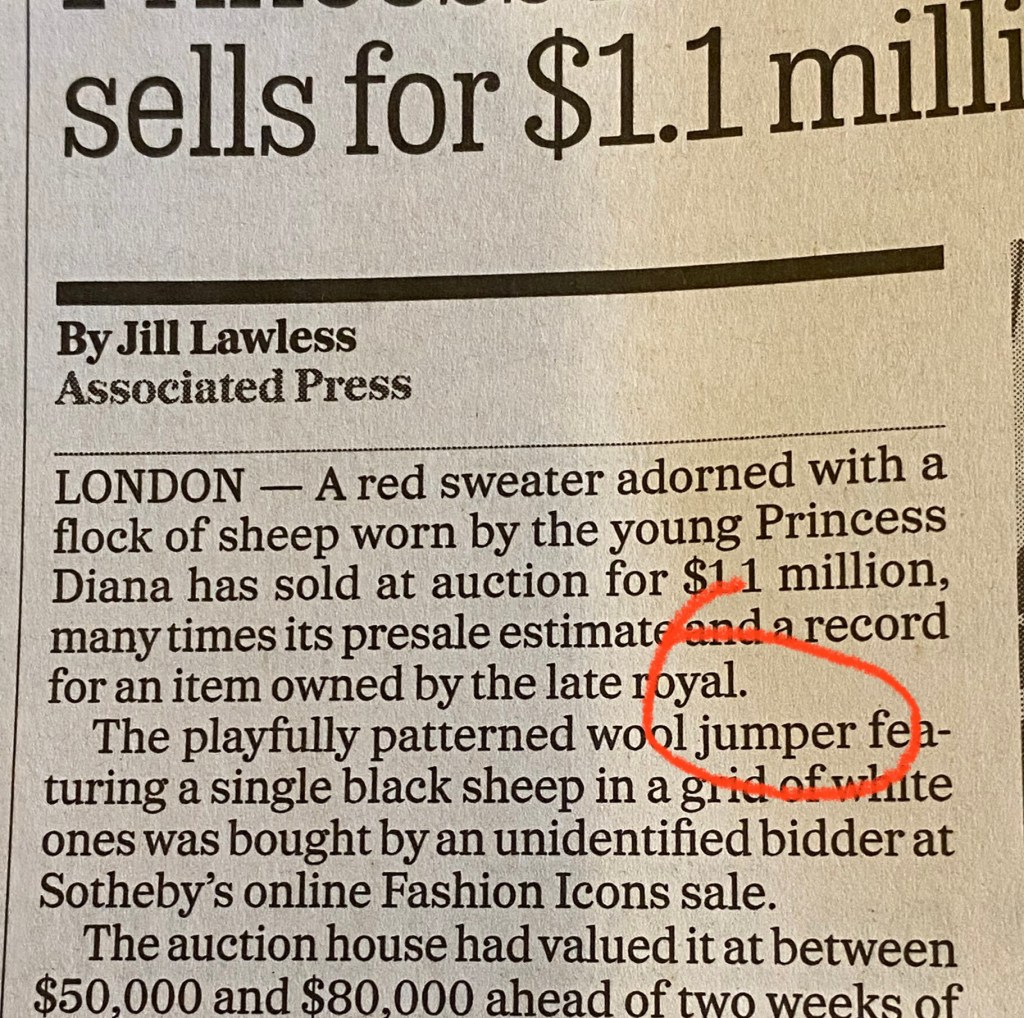

This headline, which appeared in the New York Times yesterday, reminded me of someone’s suggestion (please remind me if it was you!), months back, that I do a post based on the title of journalist Tracy Kidder’s most recent book, Rough Sleepers: Dr. Jim O’Connell’s Urgent Mission to Bring Healing to Homeless People. The Times’ review in January 2023 helpfully explains that the book “follows Dr. Jim O’Connell, a Camus-quoting, onetime philosophy graduate student turned Harvard-trained physician who, since 1985, has been treating Boston’s most vulnerable unhoused population: the city’s ‘rough sleepers’ (a 19th-century Britishism and Dr. Jim’s preferred term).”

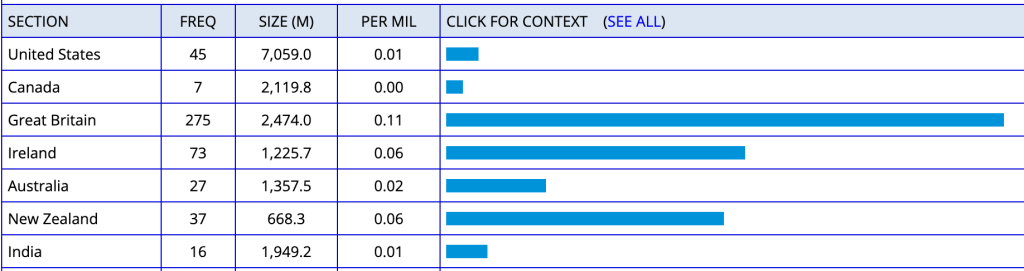

The OED shows that variations of the expression goes all the way back to the seventeenth century. A New Dictionary of the Terms Ancient and Modern of the Canting Crew (1699) has a definition of a verb form: “To lie Rough, in one’s Clothes all Night.” An 1824 Walter Scott novel has “sleep rough,” and a 1996 issue of Big Issue (the magazine sold by unhoused people) contains the line, “After 18 months living rough I went to Hammersmith Hospital and asked a doctor to help me.”

A quote from a 1987 New York Times article by Francis X. Clines, datelined London, actually predates that:

Up from skid row, Freddie Hooper is living like a lord now – one of the ”dossers,” or welfare recipients, newly ensconced in a 14th-century manor house purchased by an iconoclastic millionaire with a name and attitude straight from Dickens: Philip Stubbs.

”I tend to drink and live rough in the streets,” said Mr. Hooper, claiming sobriety lately in homage to the stately hearth that is his incredible new place in life. ”Mr. Stubbs has given me a home. What more can you say? A terrific man, Mr. Stubbs.”

The OED‘s first cite for the noun phrase in the title of the Kidder book is from a 1925 British novel: “It’s quite true, sir, that he’s a rough sleeper. Hasn’t slept in a bed since I’ve known him.”

As for U.S. use, I’ll first note that Americans have long said “live rough” in the broader sense of a bare-bones, rough-and-tumble existence. (And if you weren’t familiar with the other meaning, the Anchorage headline could be read that way.) The more narrow sense of “sleep rough” and “live rough” to mean an unsheltered existence started cropping up in the Times about twenty years ago. Here’s are some quotes:

- “In [director Michael] Levine’s vision of 21st-century disorder, Siegmund, Sieglinde and Hunding live rough on a construction site; overhead are spider webs of girders and catwalks.”–opera review of Die Walküre, 2004

- “Mr. Brigham knows the names of other homeless men who died sleeping rough.”–2007 article about the homeless in New Jersey.

- “Attitudes toward people living rough in the area — already curdling when the fires struck — hardened further.”–2022 article about the homeless in Chico, California.

- “In New York City, there are many rules on the books that have been used to restrict sleeping rough.”–2023 article

As Thanksgiving approaches, you’ll forgive me if I close with an expression of gratitude for the roof over my head and a wish that in the coming years we’ll have less occasion to use this expression, in whatever form.