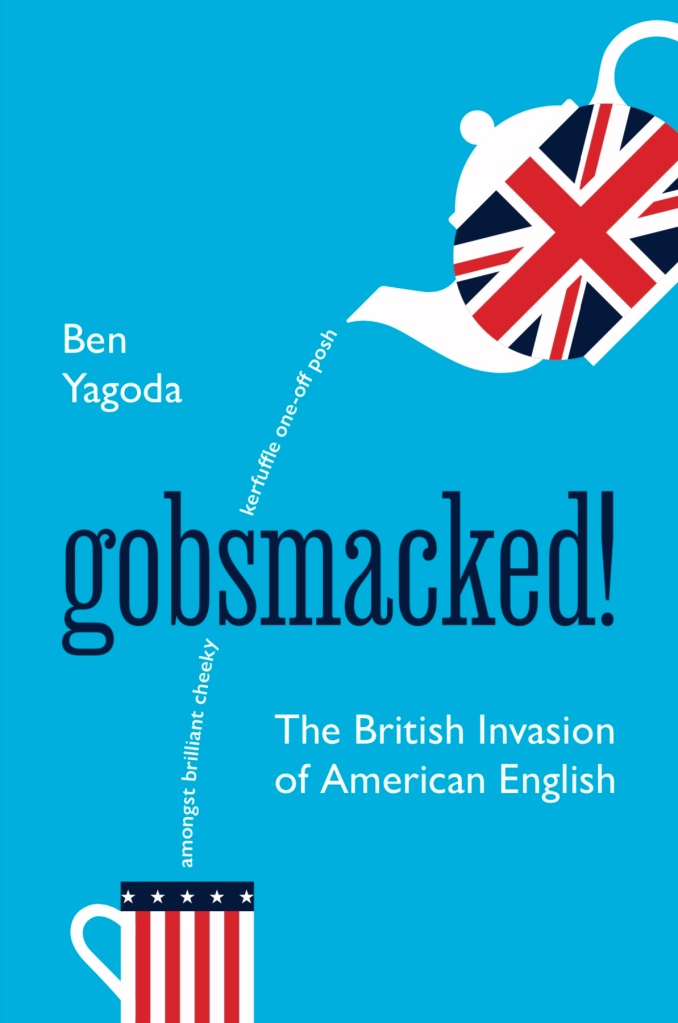

I’ve mentioned here before that I’ve put together a book based on this blog. I’m happy to announce that it has a publisher (Princeton University Press), a publication date (September in the U.S., November in the U.K.), a title, and a brilliant cover (designed by Chris Ferrante):

I’m especially pleased by the use of Gill Sans for the subtitle and my name, as it is in itself a Not One-Off Britishism.

Already, the book has received some great endorsements from really distinguished people:

- “The best exploration of British and American lexical variation and change that I’ve ever read. Or, to put it in the terms of this book: it’s brilliant, gobstoppingly spot-on, streets ahead of anything else.”–David Crystal, author of The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language

- “One could do worse than to have a lie-in with this valuable and entertaining book, in which Ben Yagoda gets his Britishisms sorted for our benefit. Brilliant, in the best American sense!”—Mary Norris, author of the New York Times bestselling Between You & Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen

- “Ben Yagoda is one of our most insightful and entertaining commentators on language and culture. In Godsmacked!, he focuses his formidable talents on an original and fascinating story: Britain’s growing influence on U.S. speech. If you’ve ever wondered why you have suddenly started saying things like cheeky, dodgy, or twee, you’d be bonkers not to devour this wonderful book.”—Fred R. Shapiro, editor of The New Yale Book of Quotations

- “Despite my decades of experience with English on both sides of the Atlantic, and all my academic study of its varieties, Ben Yagoda’s delightful book taught me things I had not yet realized about the British influence on American speech. As anyone acquainted with Yagoda’s writing might expect, his book is both fascinating and fun.”—Geoffrey K. Pullum, University of Edinburgh, coauthor, The Cambridge Grammar of the English Language

As I say, the book won’t be available for several months, but pre-orders are always helpful, as they show the publisher that people are interested. If you’re so inclined, you can pre-order here.

When events or interviews are scheduled, I will announce them here.

One one more thing. I could not have written the book, or sustained the blog for so long, without its corps of discerning, clever (in both the British and American senses), and passionate readers and commenters, many of whom are quoted in the book. So a big ta to you all, and TTFN.