“So who should be most brassed off by this show?”–Jason Farago, New York Times, June 1, 2023, in reference to “It’s Pablo-Matic,” an exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum, which he did not like.

When I came to the phrase I’ve put in italics, it sounded like a Britishism, and it is. Green’s Dictionary of Slang defines it as “irritated, fed up, annoyed,” and has two 1940 citations, one from a book called A. A. S. F. (Advanced Air Striking Force, by Charles Gardner: “Cobber said he was ‘brassed-off,’ especially after he had got half-way home once, only to be called back to hand over his flight and teach two new-comers the way around.” Neither Green’s nor the OED has anything to say about etymology, but it would appear to be a combination of the verb “brass off,” meaning to complain, which is seen in British service slang as early as 1925 and “browned off,” meaning annoyed, which popped up no later than 1931.

Observers at the time had some fun describing the differences among those two phrases and another new one, “cheesed off.” A 1943 Time magazine article on RAF slang reported: “Among thousands of Americans, ‘browned off’ already means fed up. (‘Brassed off’ means very fed up and ‘cheesed off’ is utterly disgusted.)”

And a 1943 book called Women at War had these index entries:

“Brassed Off. See Browned Off.

“Browned Off. See Cheesed Off.

“Cheesed Off. See Brassed Off.”

In Britain, “brassed off” got pretty popular pretty fast. A short story by Herbert Bates which was published in a 1942 book has this passage:

He spent most of the rest of his life being brassed off.

“Good morning , Dibden, ” you would say. “How goes it?”

“Pretty much brassed off, old boy.”

“Oh, what’s wrong?”

“Just brassed off, that’s all. Just brassed off.”

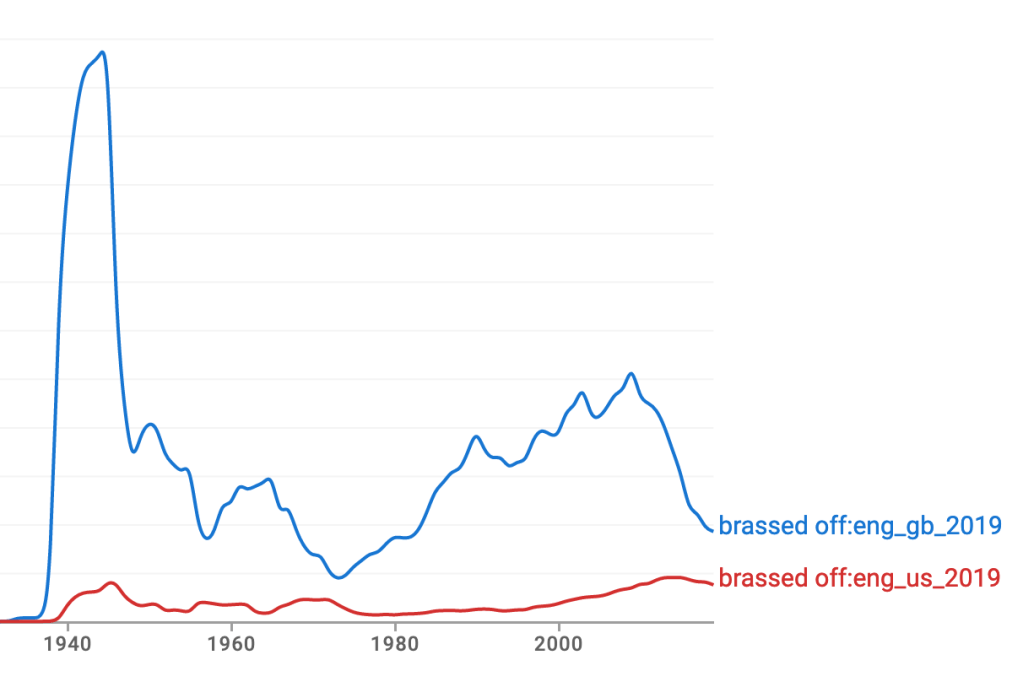

In Britain, the phrase fell off in popularity after the War, but started picking up again in the 1980s, as this Ngram Viewer chart shows:

In 2004, the BBC ran a TV series called Brassed Off Britain, which endeavored to identify the things the country found most annoying. (Junk mail “won,” followed closely by banks and call centres.)

But the phrase has never taken hold in America. Until the line from Jason Farago quoted above, it had never been used in the New York Times by an American writer or source, except in reference to Brassed Off, described by the Times as “a funny and poignant [1997] film set in a bleak Yorkshire mining town.” Similarly, it does not show up at all in the Corpus of American Historical English or from any American sources in News on the Web (NOW), a corpus of more than 17 billion words published since 2010.

So well done, Jason Farago! You have perpetrated a true One-Off Britishism.

There are yet other uses in English-English for the term ‘Brass’.

‘Brass’ was – probably still is – a British military term for ranking Officers on account of the amount of uniform-metal-work on display. Therefore, for an ordinary squaddie, being ‘Brassed-off’ was a reprimand.

Both ‘Cheesed off’ and ‘Brassed off’ can be used in polite conversation, though in the boozer down the road you’d more likely hear the term ‘P*ss*d off’, meaning the same thing with somewhat greater emphasis. (Not to be confused with the exact same phrase meaning to leave abruptly!)

But Brass, in all this can be used in other contexts.

‘Brass’, in the North of England, also means ‘money’…… “where there’s muck, there’s brass” etc.

‘Brassy’, as well as meaning a form of speech or dress to ostentatiously, be ‘in your face’, can also mean very cold weather, as in the expression “Brass Monkeys, tonight, Mate!” ( in full, “It’s cold enough to freeze the b*ll*cks off a Brass Monkey).

Though, the question remains, does this trivia travel well?

the term “brass” in the sense of high ranking officers in the military is used in the US as well. the full phrase “brass hats” is also used

Indeed, “brass” in this sense was not used in Britain till well after World War II and hence would seem to have no connection to “brassed off.”

Not sure about “brass hats” but the term “top brass”, meaning senior members of the armed forces, appears to have emerged in late 19th century Britain.

OED labels brass as “originally U.S.” and has this definition and first citations. (Beloit College is in Wisconsin.)

High-ranking officers in the armed forces collectively. Frequently with modifying word intensifying the sense of distant seniority, esp. in top brass (also big brass, high brass, etc.). … [By metonymy, with reference to their brass or gold insignia.]

1870 Beloit College Monthly Oct. 12 At every big plantation or negro shanty yard Just to save his property the generals plase a gard The sentrys instruction to let no private pass, The rich mans house and table are fixed to suit the brass.

1899 Boston Herald 26 July 4/8 It was not a big brass general that came; But a man in khaki kit.

The first citation for “top brass” is British, but from 1971. “Brass hat,” however, was established earlier in Britain, as in this quote from 1904: “Whether some ‘brass hat’ might not come round and inspect us next day.”

I remember my Grandmother using “top brass” to mean high ranking officials in the sixties here in England.

My father always used “brassed off” to mean irritated and I believe he used it to mean a personal reaction to a situation that someone found irritating. Indeed some people, as in Ben’s excerpt from the Bates’ story, were “perpetually brassed off. I don’t think that it fits well in respect of a critical or aesthetic response to an exhibition where the response is surely not annoyance or irritation but disagreement or perhaps argument. When I read the original review I thought the use of “brassed off” was a clanger.

The OED should look harder. From a debate in the House of Commons Volume 524: debated on Tuesday 2 March 1954 ( reported in Hansard, the official record), six mentions of “top brass” by The Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Defence (Mr. Nigel Birch) including ‘ We all remember Paschendaele and how the “top brass” were supplied with troops, who were “pushed around.” ‘

Thanks–I love Hansard. The quotation marks/inverted commas around the phrase indicate fairly recent coinage, so I would still say no connection to “brassed off.”

The author Herbert Bates, better known as H. E. Bates, went to my old school. He was there 50 years before I was, and yet his old English teacher was not only still alive, but came in to give us a talk.

I think I’ve heard ‘a brass’ used to mean a prostitute, but I can’t remember where or when. London, probably, around 40 years ago. Ah yes, here it is, definition 9: https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/brass

By ‘Herbert Bates’ do you mean H E Bates?

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/H._E._Bates