My word for the many, many (, many) comments that have come in since BBC.com featured NOOBs in Cordelia Hebblethwaite’s excellent piece about Britishisms in American English. I have to approve them all before they’re posted, and they are so generally clever and well-written that I don’t want to rush the process–that it, I read them all and comment on some. I’m only about halfway through, the redundancy (not in the British sense) is my fault, not the commenters’.

Year: 2012

“Endeavour”

All the coverage of the Space Shuttle Endeavour’s ongoing cross-country farewell tour made me wonder, naturally, about the ou spelling in its final syllable. It turns out it was named–u and all–after the first ship commanded by the eighteenth-century English explorer James Cook. It’s not a natural spelling for us Yanks, hence this mistake in a sign some well-meaning NASA folk constructed to cheer on a 2005 launch:

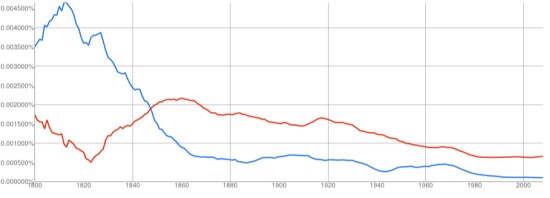

Despite the shuttle’s fame, the u-less spelling (indicated by the red line on this Ngram chart, showing use of both spellings in American English between 1800 and 2008) remains a strong preference on these shores, as it has been since 1850:

“Opening Hours”

In the previous post (piece of kit), I promised to feature another Nancy Friedman find. It’s “Opening Hours,” capitalized because it’s what you see on the signs of retail establishments in the U.K., indicating what U.S. stores would announce, simply, as “Hours.”

Nancy sent along a link to a profoundly twee-seeming San Francisco establishment called MAAS & Stacks, which describes itself as “a purveyor of classic pieces with modern tailoring. Inspired by the simplicity of a well-constructed garment, the store aims to present customers with a curated selection of everyday wears.” Their opening hours don’t commence till noon on weekdays; I guess they need extra time for curating.

In these parts, two examples constitute a trend, so I offer this, also from a posh West Coast outfit:

“Piece of kit”

Nancy Friedman has once again alerted me to to a NOOB of which I was not aware. (If you want to know about the other occasions, just key her name into the search field at right.) I was certainly familiar with the BrE kit, meaning both “uniform” (what football players wear) and “equipment,” and had indeed been keeping my eye out for American uses.

Thanks to Nancy, I now know the latter kit, at least, has established a capacious beachhead on these shores. She sent along a link to a September 14 blog post by John Scalzi, about the new iPhone, which includes this line: “As advertised, it is a very lovely piece of kit.”

I poked around the Web for other uses and found it’s most popular among techies like Scalzi. Thus Zack Whitaker, on ZDNet: “It doesn’t matter where you are in the world: a media on-the-go bag has to have every piece of kit you may or may not need.” And Elizabeth Fish, in PCWorld: “The Sandia Hand by Sandia National Laboratories is an impressive piece of kit for a troop to own.” (Both quotes appeared in the last couple of months.)

Besides spotting this rather annoying piece of pretentiousness, Nancy offers a credible starting point for its U.S. popularity: Lenny Kravitz’s 1999 song “Black Velveteen,” which refers to a “nice piece of kit.”

As if all this weren’t enough, Nancy has identified another new NOOB. Watch this space to learn about it.

Oh, come on

In a profile of the director Robert Wilson in the September 17 issue of the New Yorker, Hilton Als relates how Wilson studied as an undergraduate at the University of Texas in his native state. Als then writes:

“While at university, where he enrolled in business administration to please his father, he took a job as a kitchen aide at the Austin State Hospital for the Mentally Handicapped.”

The “at university” sets a news standard for conspicuous and gratuitous use of Britishisms (CAGUOBs), even for the New Yorker.

“Fingers crossed”

Yes, yes, I know this is a venerable U.S. expression, so hold your fire. Americans say things like “My fingers are crossed” or “Keep your fingers crossed,” to indicate a wish for good luck. The Brits like to use the phrase by itself, as Americans would say, “Good luck!”, or, similarly, to more or less mean, “Here’s hoping for…” An example is this headline from the local newspaper in the West Midlands town of Solihull: “Fingers Crossed for a Sunny Shirley Carnival.”

I have some sense that the expression is in the early stage of incipient NOOB-itude. I offer this from Andy Benoit’s New York Times preview of the NFL Dallas Cowboys: “The budding star receiver (fingers crossed on off-field matters) Dez Bryant is 23.”

And this quote from American Canadian director James Cameron, about the recent release of his most famous film on Blu-Ray: “We’ve been holding back Titanic. So, fingers crossed.”

“Do” (food)

Among the no doubt hundreds of meanings of the verb to do is a particularly British one. It relates to food in general or a particular dish; the American equivalents are serve or offer. Thus an English tennis partner of mine once described a dinner part in which he “did pass-ta [the first syllable rhyming with class] and turkey.” Or one might inquire of a pub, “Do you do meals?”

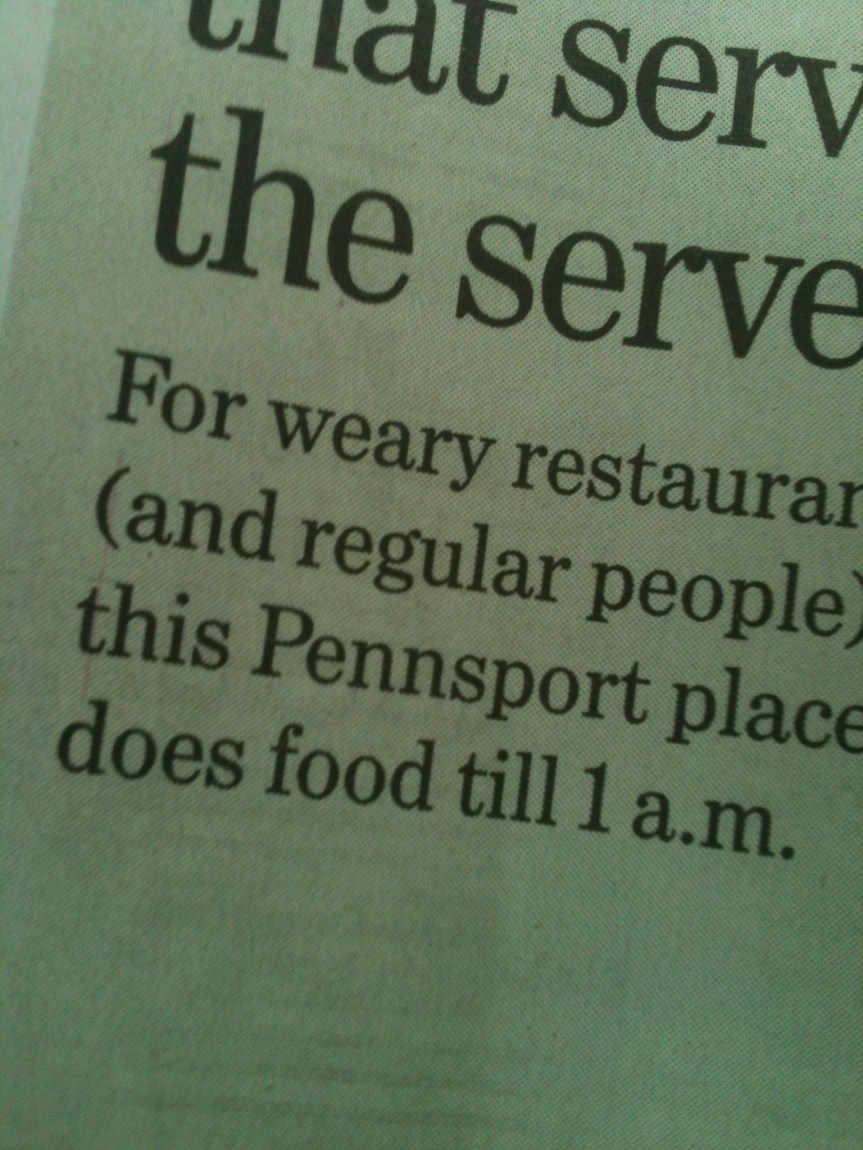

I have been on the lookout for American uses of this do, with no luck until a couple of says ago, when I spotted this headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer:

So let’s see if do does America.

The B-Word Spreads Its Wings in Retail

“Directly”

The British use this adverb, in a time sense, where Americans traditionally use right or immediately or just, most commonly in such phrases as directly after or directly before, but also by itself, to mean straightaway, as in this line from Jane Eyre (1847): “He sat down: but he did not get leave to speak directly.”

It is popping up over here, prominently in a Sam Sifton New York Times Magazine recipe for rosemary-garlic crusted pork butt that I aim to make tomorrow night (I will let you know how it goes):

“These [peaches] you will cut in half and pit, directly before cooking.”

And there is also:

- “CBS is preparing online specials for directly before and after its television coverage, the latter anchored by Scott Pelley.” (Philadelphia Inquirer, August 25, 2012)

- “Maj. Gen. Paul Lefebvre retired during a small, private ceremony directly before handing command of Marine Corps special operations to Maj. Gen. Mark Clark…” (Jacksonville Daily News, August 24, 2012)

- “Littlepage stated that directly after hearing the noise, her steering wheel began to jerk from side to side.” (Surfky.com News, August 25, 2012)

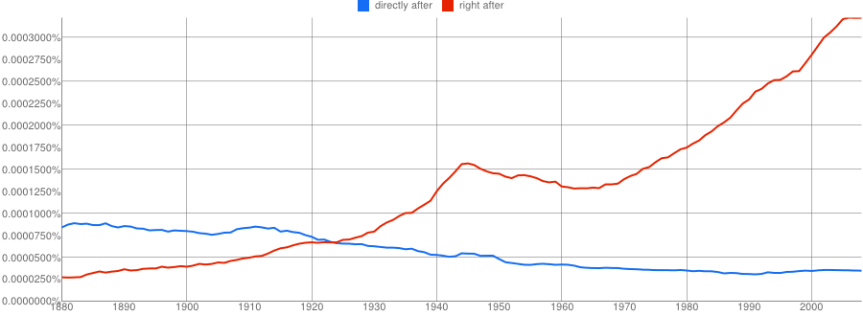

I used Google Ngram to compare relative frequency of right after and directly after in the U.S. because I couldn’t figure out any other way to isolate this meaning from all the (many) other ones directly has. The results in the chart below show that right after (red) overtook directly after (blue) in about 1925, but that d.a. stopped the lexical bleeding in the ’90s and is starting on the road back. (In Britain, directly after didn’t take the lead till the ’50s and even since then has had a respectable showing.)

NOOBs Among the Constabulary

From today’s New York Times:

The following morning, [suspected burglar Piotr Pasciak] was awakened by police officers in his [Brooklyn] bedroom. One of them said, “Easy, peasy, lemon squeezy,” first handcuffing, then dressing Mr. Pasciak, he said.

Thanks to Gigi Simeone.