Takeout and takeaway (hyphenated versions are also commonly found) refer to food purchased in a restaurant or other shop and consumed at home. Both terms can be adjectives or nouns and can refer to the meal itself or the establishment that prepares it. OED describes take-out as “orig. U.S.” and finds it first in a line from James M. Cain’s 1940 Mildred Pierce: “Pies she hoped to sell to the ‘take-out’ trade.” Again according to the OED, take-out arrived in the U.K. no later than 1970, when The Times reported, “One of New York’s finest restaurants will provide gourmet ‘take-out’ lunches for the hard-pressed executive.”

By contrast, all of the OED’s citations for takeaway are from the U.K. or British Empire outposts, commencing with a 1964 quote from Punch: “Posh Nosh‥was serving take-away venisonburgers.”

Takeaway (in the food, rather than the golf-swing, football-interception-or-fumble, or business-jargon, sense) felt strange in the U.S. as recently as 1977, when the New York Times noted about Terence Conran’s new New York furniture store, “delivery is discouraged, and everything stocked carries a tag that says, ‘takeaway price.'” But it has made itself comfortable over here in recent years–for example, in this headline two days ago from the blog Culturemap Austin (Texas): “Fresa’s Chicken al Carbon brings a giant chicken mascot and fresh take-away food to Austin at a decent price.”

Or this from a New York Times review last year of a Brazilian restaurant in Queens: “For takeaway, banana and cassava cakes ($2.75 each) travel well.”

Thus, for my money, takeaway is a clear-cut NOOB. However, I have a nagging sense that I encountered it long ago (I’m talking a half-century) in the Washington, D.C., area, and at the time did a mental double-take to find it instead of the more familiar takeout.

Normally, when I want to look up a word in the Dictionary of American Regional English (DARE), I’m frustrated, because I only possess Vol. V., which covers Sl-Z. I got excited because both takeout and takeaway fall within its purview. However, DARE doesn’t have an entry for either one. Help?

Update, 4/21: The comment from Laura Payne, below, made me realize I was mistaken about remembering takeaway being used in Washington. The term I actually encountered was carry-out.

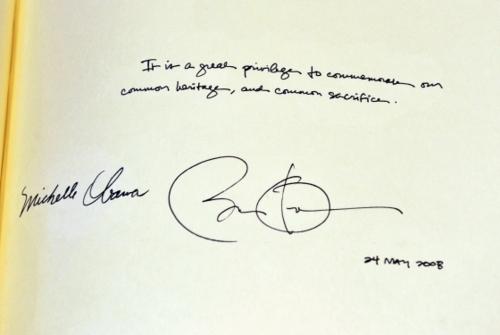

My friend Andrew Feinberg e-mailed me as follows:

My friend Andrew Feinberg e-mailed me as follows: