I was reading a transcribed conversation of New York Times theater critics a couple of weeks ago and came upon this comment, uttered by Matt Wolf, about the London production of Evita: “I was especially poleaxed in that show by the young American Diego Andres Rodriguez as the narrator Che…” That word “poleaxed” wasn’t familiar to me. It felt like a Britishism.

Google Ngram Viewer confirms that it is. (And by the way, Wolf turns out to be an American who has lived in Britain for 30 years.)

But what does it mean? The word has a long history, beginning as a noun. The OED‘s definition begins:

“Originally: a weapon for use in close combat, existing in various forms but generally having a head consisting of an axe blade or hammer-head, balanced at the rear by a pointed fluke. Later also: any of various long-handled weapons of this type, as carried (now only ceremonially) by the bodyguard of a monarch or great personage. b. A similar shorter weapon of this type used in naval warfare until the end of the 18th cent. for boarding, resisting boarders, cutting ropes, etc.”

The first citation is from 1294. Later, it referred to an ax used in slaughtering cattle; a verb form appeared in the nineteenth century. Interestingly and surprisingly, the OED‘s first citations for a figurative use–meaning striking someone with close to the impact of actually poleaxing them, came from a U.S. source, the Zanesville, Ohio, Signal in 1927: “That overnight punch with which he pole-axed Jimmy Maloney on Friday night has made of him the greatest potential fighter of them all.” And so did the first time it was used as a simile, from the Baltimore Sun in 1954: “The poor lady sits down in a daze, as if pole-axed.”

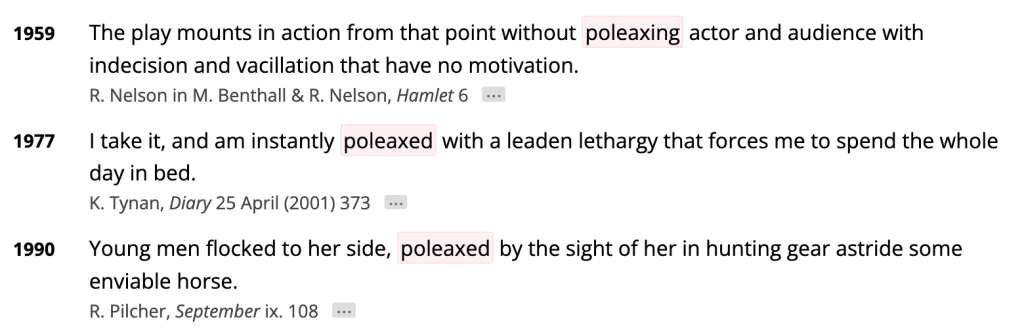

But the next step–its use to mean “To stupefy, stun, or overwhelm. Frequently in passive.”–was first seen in Britain, and became a popular metaphor there, as the the Ngram Viewer graph suggests. The OED‘s first citations:

America followed along, and by the end of the 2010s, the term was pretty robust here, as witness some quotes on Merriam-Webster’s site:

- “Moreover, some strong farm and minerals prices persisted even after the financial-sector debacle of 2007-09 put the general U.S. economy into recession and poleaxed the stock market.—Twin Cities, 2019

- Iran’s oil production has dropped by 1.5 million barrel a day over the past year, poleaxing the Islamic Republic’s economy. — Time, 2019

- “House Republicans, who began the week with just 40 days of work left on their calendar — seriously, check for yourself — will have spent four of them being poleaxed on issues that divide their conference and alienate most voters. — Washington Post, 2018

There’s one more sub-meaning, at this point strictly British, and pointed out to me by my West Ham–supporting friend David Friedman. I forgot the exact way he described it, so I asked Google AI for a definition. It replied: “In a football context, to be ‘poleaxed’ means a player has been hit or tackled so hard that they are completely knocked down or ‘upended,”‘often falling to the ground as if struck by a heavy blow.” AI goes on:

“General Commentary on Fouls: Commentators use the term when a player is completely upended or knocked down in the penalty area in what appears to be a clear foul, often leading to debates about whether a penalty should be awarded. Examples include:

- Sunderland manager Phil Parkinson claiming Joel Lynch was ‘absolutely poleaxed’ in the area during a match.

- Commentary on a St Johnstone vs Rangers match where goalkeeper Alan Mannus was said to have ‘crudely poleaxed’ striker Alfredo Morelos.”

Ouch.

There’s a famous controversy over the phrase in Hamlet, where Hamlet’s father is said to have “smote the sledded polacks on the ice.” Note to Hamlet, 1.1.63: “sledded Polacks”

Act 1, Scene 1, line 63

This is a famous crux (a passage which invites different interpretations). The two versions of Hamlet published in Shakespeare’s lifetime, the First Quarto and the Second Quarto, have “sleaded pollax,” which doesn’t make good sense. The First Folio (the first collected works of Shakespeare, published after his death by two of his fellow-actors) has “sledded pollax.” Edmond Malone (1741 – 1812), famous editor of Shakespeare, emended the “pollax” to “Polacks.” However, King Hamlet was at war with the King of Norway, not the Poles, and so some editors emend the phrase to “leaded pole-ax.”

https://shakespeare-navigators.ewu.edu/hamlet/Hamlet_Note_1_1_63.html

I suspect it simply referred to “Polacks,” transporting their troops via sleds.

I must travel in violent circles without appreciating that. I think of this as a fairly common term– used metaphorically, of course– mostly, as Ben mentions, in sports or politics.

Sorry to see you voluntarily using AI rather than avoiding it. I liked “Gobsmacked” and that’s why I started following this blog, but I’m going to be unfollowing it now.

“I was especially poleaxed…” – Can one be especially knocked to the ground, especially struck by lightning, especially dead, and so on? Living in Britain for 30 years was clearly not long enough to learn British English, particularly as ”I was particularly poleaxed” goes begging.

“Young men poleaxed by the sight of her in hunting gear astride some enviable horse…” – I prefer “envied”; can anyone explain to me why I dislike “enviable” here?

By the by, this equine intimation often crops up (geddit) and must be older than Lady Godiva. I’ve just read Laurie Lee recalling his youthful response to the poetry of Roy Campbell:

“…sisters called to their horses, naked in the dark, and met them with silken thighs…What had I read till then? – cartloads of Augustan whimsy; this I felt, was the stuff for me”.