By JACK BELL

So there is this American television network that is carrying all 31 games of the European Championship, the continent’s soccer jamboree that starts today in Poland and Ukraine.

On Wednesday, ESPN hosted a telephone conference call with the on air “talent,” as the industry calls its announcers. Both of the guys – Ian Darke and Steve MacManaman – are British. So that means another month of British accents spilling out of TV sets across America. Another month? Make that more, much more.

I love many, many things English: The Beatles, Stones and Clash; Beeston Castle; Mousehole in Cornwall; Stilton cheese; Manchester United; Cockney rhyming slang; and there once was this a girl (another story). But over the years, I’ve come to draw the line at the so-called “language of soccer,” where every chip is “cheeky,” every player on the wing is “nippy,” every field is a “pitch,” every pair of cleats are “boots,” every uniform a “kit” and every big play is “massive, just massive.”

I learned my soccer (sorry, we don’t call it football and even though the Brits like to give us stick for calling it soccer, it’s actually their word, derived from aSOCCiation football) from a collection of British counselors at a summer camp in the Pocono Mountains way back in the 1960s. We got called all kinds of names for wearing strange uniforms (not kits), high socks … you get the idea. But soccer taught me about the world, in a lot of different accents and languages. My travels have been soccer travels. My friends are soccer friends.

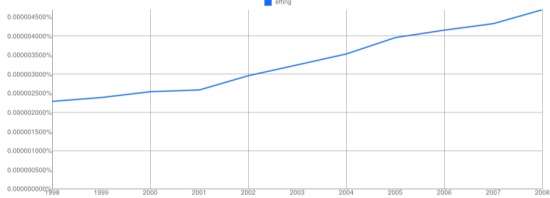

But now, as the game is seeping deeper and deeper into the American consciousness, some pooh-bahs somewhere (ESPN, Major League Soccer, Fox Soccer to name three) have come to the conclusion that to sound authentic the game in the United States has to, must to, adopt the Britlingo of the game.

And it’s especially absurd, in my view, for M.L.S. to indulge this soaring perversion. On its own Web site, MLSsoccer.com, the prose is rife with Britishisms that can confuse and mislead the casual reader, me included. Do you know what a “brace” is? I had never heard the word until a Fox Soccer report. Then it popped up again on the MLS Web site. I had to check the dictionary. And I’ve been following the game for longer than I care to remember. I had never, ever heard the term. Why confuse people? Can’t we just say “Francochino scored two goals”? Why make it mysterious.

What’s more the league – remember it’s called Major League SOCCER – has for some reason allowed a handful of teams to append the letters F.C. to their club names. That stands for Football Club. That’s fine if you’re in Burnley or Bristol (England, that is), but it’s patently absurd in the U.S. (maybe more acceptable in Canada for Toronto, a team without a nickname, imagine!, and the Vancouver Whitecaps). But F.C. Dallas? Seattle Sounders F.C. Laughable.

Fox Soccer has been the pre-eminent transgressor for a couple of reasons: The network’s lead soccer producer is a gruff (I’ve been told) Scotsman who insists on the Britlingo and some odd pronunciations of other words and names. Hence we have JuvenTOOS when every one in the world says Juventus. Just to be different? I think not. In addition, an anchor I once exchanged email with told me that the channel was catering to expat viewers who simply would not abide the Americanization of soccer lingo. Really? Next stop is the WC (water closet).

So there I am, watching Fox Soccer’s nightly report and on comes a story about something called a “tapping up” scandal. Sorry, but WTF? Again, I had never, ever heard the British term for a bribery scandal. Ever. I also broke for the dictionary when another announcer used the word “scupper” to describe something gone wrong. So what’s a scupper? It’s a nautical term for the spaces on deck that allow water to flow back into the sea. Get it? Man overboard.

My latest pep peeve is ESPN’s wholesale plunge into Anglophilia (I know, that sounds really bad). Ian Darke has emerged as the network’s No. 1 play-by-play man. He’s as talkative as some of the worst American offenders, but what’s worse, he insists on using the most obscure British terms during broadcasts. Some players are at “sixs and sevens.” Huh? Wha? Are you kidding me. And the man simply will not allow the game to do its own talking. Even the network’s M.L.S. broadcasts have a Brit doing the games (the generally benign Adrian Healey) and the newest entry in the national soccer TV landscape, NBC Sports Network, hired one Arlo White, another Brit. (Here I’ll give a pass to the former GolTV color man, Ray Hudson, who is most entertaining, in any language.) I don’t want to start a contROVersy, but it’s getting harder and harder to take.

These terms are not the language of soccer … they are the clichés of soccer and should be recognized for what they are. And they are spreading like Kardashians as more and more people latch on to the world’s sport and think they’re speaking the game’s lingua franca. They are not. Ask an authority as authoritative as the long-time columnist Paul Gardner, an English native who has called New York home for more than 40 years. The only Britishism he’ll use about this topic is “rubbish.” Brilliant, just brilliant.

As I mentioned before, there are many, many things I love about Britain, particularly the facility with the language of so many people. The inventiveness that is often missing in American discourse. But do we say “lorry” for truck? Do we say “loo” for bathroom? Do we say “lift” for elevator. Not bloody likely. We have our words, they have their words. Can’t we just agree to disagree on this? O.K., back to the games on the telly.

Jack Bell is an editor in the sports department at The New York Times; and also edits and writes for the Times’s Goal blog. He can be reached at (no, not on) bell@nytimes.com.