A line in David Carr’s column in the New York Times a couple of days ago caught my eye: “Fumbling an editorial change may seem like small beer when viewed against the backdrop of an industry in which bankruptcies are legion and rich business interests are buying newspapers as playthings.”

I wasn’t familiar with small beer, but it had the ring of a NOOB, so I investigated. The first OED definition is “Beer of a weak, poor, or inferior quality” (what Americans might call near beer). The second, by extension, relates to Carr’s meaning: “Trivial occupations, affairs, etc.; matters or persons of little or no consequence or importance; trifles.” Or, what Americans would typically term small potatoes.

Although Shakespeare does use the term in “Othello,” the OED quotes Joseph Addison rather purposely and self-consciously crafting the metaphor in 1710: “As rational Writings have been represented by Wine; I shall represent those Kinds of Writings we are now speaking of, by Small Beer.” The next quotation is from John Adams, who wrote in 1777, “The torment of hearing eternally reflections upon my constituents, that they are..smallbeer [sic],..is what I will not endure.”

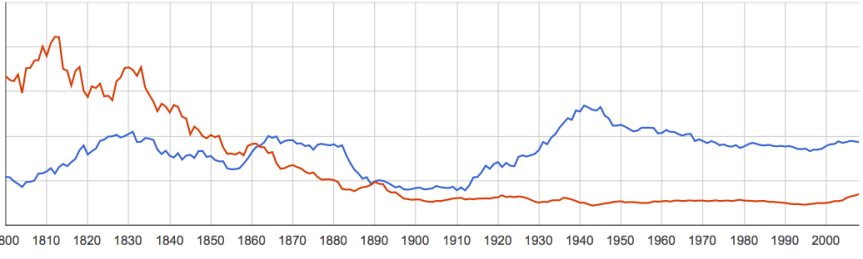

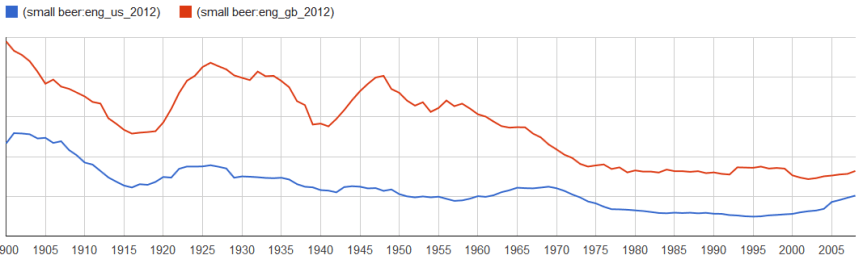

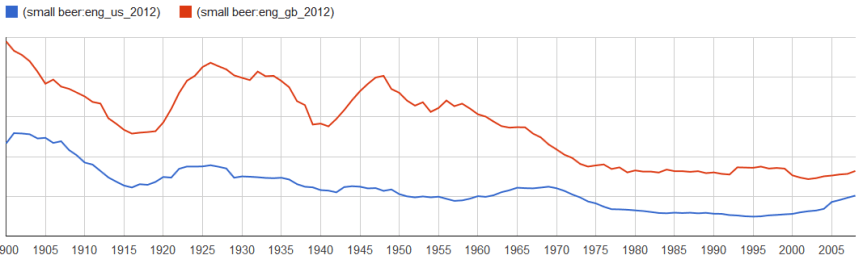

Adams, of course, was an American, and therefore small beer isn’t a NOOB along the lines of gobsmacked or toff. But I do classify it as a “Historical NOOB.” Back in 1777, there wasn’t any, or much, difference between the way Englishmen and Americas used the language. Over the years, however, this particular expression, like many others, acquired a British patina; all post-1777 OED citations are British. The Google Ngram chart below shows use of the phrase in Britain (red line) and the U.S. (blue line) between 1900 (by which time it was mostly used metaphorically) and 2008. Up until the mid-2000s, it was used between two and three times more frequently in Britain.

Google’s data goes up only to 2008, but I would imagine that by now blue and red lines have met, or are about to. That is, small beer is getting some U.S. traction. Stanford Professor David M. Kennedy, writing for CNN after the recent election, regretted that “as committed a change agent as Obama is doomed to four more years of nothing more than Lilliputian, small-beer tinkering.” In September, a Los Angeles Times writer observed, “Of course, in San Diego a dispute that has lasted only a decade is but small beer.”

Another colorful British food metaphor has had less success over here. I refer to hard cheese, i.e, “tough luck.” (That brings to mind another Britishism, the one-word sentence that’s a favorites of sports commentators, “Unlucky!” No spottings here as yet and I don’t expect there ever to be.) A fair amount of hard cheese searching yielded only a couple of hits, both of them facetious. In 1990, New York Times columnist Tom Wicker channeled the notoriously preppy then-President George H.W. Bush: ”Gee, fellows, we can talk about anything but maybe the graduated income-tax thing; but, golly, if there’s going to be an increase, sorry, hard cheese, but you Democrats have to propose it. Then I’ll just have to tell the taxpayers I’m going along only because you big tax-and-spenders left me no choice.” And a St. Louis Post-Dispatch columnist wrote in 2007: “It’s a cold, cruel, capitalist world out there, Bunky. You put in your 20 years in the gunk at the chemical plant and one day . . . whack! It’s all over. It’s hard cheese for you and your family.”

All the rest of the American uses I encountered referred either to dairy products or to baseball, where the expression is an accepted elegant variation for fastball. From a New York Times recap of a 2010 game: “So, at 3-0, Robertson threw Young some hard cheese at the knees for a strike.”

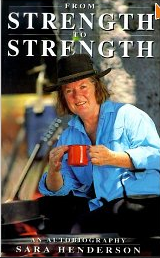

But I found that the Susan Kamil quote wasn’t a one-off, as witness this from the Yale Daily News: “After winning every Ivy game this season, the women’s volleyball team is going from strength to strength.” (October 17, 2012) And this February 2102 quote from the Times’ David

But I found that the Susan Kamil quote wasn’t a one-off, as witness this from the Yale Daily News: “After winning every Ivy game this season, the women’s volleyball team is going from strength to strength.” (October 17, 2012) And this February 2102 quote from the Times’ David