In his review of the English nature writer Robert MacFarlane’s book Underland, Dwight Garner wrote in the New York Times:

There’s the prickling sense, reading Macfarlane like [Geoff] Dyer, that a library door or a manhole cover or a bosky path might lead you not just to the end of a chapter but to a drugs party or a rave.

The sentence has led me to add a new category to the blog: “Ventriloquism.” By that I mean cases where an American writer is writing about British people or topics, and consciously or not adopts British lingo. One example in the Garner sentence is “bosky,” which Google Ngram Viewer suggests has consistently been used roughly 50 percent more in Britain than the U.S. (The word, which means “wooded,” is now pretty rarely used on either side of the Atlantic, and when it is generally precedes “glen” or “dell.”)

But I feel “bosky” is a one-off and will devote my attention to Garner’s choice of the word “drugs” instead of “drug” to describe a party in which presumably taking drugs is the dominant feature. It’s a case of pluralizing an attributive nouns, and I’ve written about it before, in the cases of “drinks menu” (instead of “drink”) and and “covers band” (instead of “cover”). Other examples include “books editor” (for the person in charge of book coverage at a newspaper or magazine) and “jobs report” (for studies and statistics about employment trends). In the post on “covers band,” I summarized some of the surprising amount of research done on the topic. For example:

In a 2002 paper, the linguist Elisa Sneed refines the work of Maria Alegre and Peter Gordon in determining the circumstances in which plural attributives tend to be used. There seem to be two important factors. The first is “abstractness.” Sneed writes: “Something not easily imagable, such as a process (admissions), an action (assists), a thing (benefits), or something that is otherwise complex (dissertations) is abstract; something easily imagable and simple conceptually, such as pencils or flowers, is concrete” (italics added).

So dissertations index sounds okay; *flowers pot does not.

The second factor is heterogeneity in the head (final) noun of the phrase. Sneed gives the example of analyst as a head noun that promotes “diversity among the entities denoted by the internal noun” and pile as one that highlights homogeneity. So we might say weapons analyst but weapon pile, as well as cookie jar and sock drawer….

Three other wrinkles. First, irregular plurals tend to be more acceptable than regular plurals as attributives. We might say mice droppings but never *rats droppings. Second, as noted by David Crystal, the plural is often used in cases when meaning might otherwise be ambiguous or misleading. Thus, in baseball, a batter who doesn’t have enough power to produce doubles, triples, or home runs is a singles hitter. To call him a single hitter might mean that he’s just one hitter, or that he’s unmarried. Finally, the plural is used in cases when a possessive apostrophe is understood, such as farmers market.

But here’s the funny thing. It seems self-evident to me that plural attributives are a strongly British phenomenon … but I’ve never seen it referred to as such in any scholarship or commentary, and I even got pushback when I asserted this in previous posts. So I’ll try to support my contention, a little at a time. In the “covers band,” I included an Ngram View chart showing British preference for the plural and American for the singular. (And by the way, Google being an American company, it’s “Ngram” not “Ngrams.”)

As for “drugs party” vs “drug party” here’s the Ngram Viewer chart for use in American books, 1990-2000:

And here’s the one for British use:

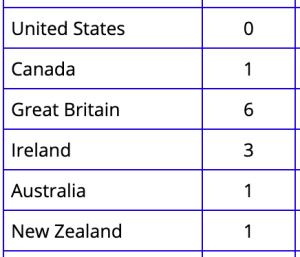

2000 is the most recent year for reliable Ngram Viewer data, but the News on the Web (NOW) Corpus, which tracks postings from 2010 to the present, shows “drugs party” being used exclusively in Britain and Commonwealth countries (though admittedly not very often).

So can I get an “amen” that Dwight Garner’s “drugs party” was a NOOB?

Next up: “jobs report.”

Amen. I agree. Although I could see drugs party being used in American if someone was describing a political party famous for its advocacy of the legalization or decriminalization of drugs.

Given the disclosures of the past weekend, I suspect that “Drugs Party” is a synonym for the Conservatives in the UK.

In Burden of Proof, Scott Turow describes his daughterâs hair as a âbosky do,â which I take to mean dark and frizzy.

Is this a typo. and you really meant “writer” ? Or have I missed some subtle linguistic metajoke ?

QUOTE

I mean cases where an American writers is writing about British people

ENDQUOTE

Typo, will fix now.

Slightly relevant (maybe!) is a sign I pass frequently on my way to work in Silicon Valley:

ROAD WORKS AHEAD

Sounds very British to me – an American would use ROAD WORK.

Amusingly, the city tried to fix the sign — somebody must have got to the road(s) department. For about a week the sign was changed to read

ROAD WOK AHEAD

Which is one for the miscorrection files.

A few months ago they re-surfaced the road that leads from my house to the centre of town and I was amused to see signs saying RAISED IRONWORKS AHEAD. It took me a while to work this out. There were no foundries floating in mid-air. What it meant, of course, was that the old tarmac had been scraped off leaving various manhole covers and drains above the surface of the road, not so much raised ironworks as lowered road surface.

(And then there’s the confusion between the meaning of pavement in the US and the UK. Over here, the pavement is the strip on either side of a road on which pedestrians can walk, in the US it’s the road surface. The term “sidewalk” is rarely used in the UK.)

Sidewalk/pavement …

i believe the difference is because in Britain most paths to the side of the road were not metalled – so when they were the term “pavement” was used to indicate so. Whereas in the US they are assumed to be metalled as a matter of course, so why use a special word ?

All dates back to the revolutionary split in the language.

I notice that modern Ordnance Survey maps no longer refer to roads as metalled and unmetalled. I wonder if the term is becoming obsolete.

When I was growing up, the town where I lived the pavements were covered by rectangular blocks called paving stones. Not sure if that counts as being metalled, as opposed to the pavements here in Guildford which are tarmacked, which is what I think of as metalled.

I have never heard the words metalled or unmettalled in my life, in reference to roads, their tributaries, or anything else. I am not an engineer, but I’ve walked on lots of sidewalks and/or pavements in many countries.

Apparently from what I see in Chambers, metal originally meant anything dug out of the ground, hence rocks used in road building were called metal. Tarmac or tarmacadam is tar mixed with small rocks. I’ve also heard that the term tarmac is less used for a road surface in the US, possibly because it’s a registered trade mark there, although it is the term used for airport runways.

In the explanation of symbols on some of the Ordnance Survey maps I bought in the seventies, some roads were described as unmetalled.

Thank you for the metal explanation. If I have ever encountered this term, I’ve forgot. And, yes, I can think of no other use for tarmac in American than airport runways. I don’t know why that is, possibly because they were/are, in fact, made of a composition that differs from the mix used to pave roads (that is usually “asphalt”), possibly because it just sounded more glamorous in the age when air travel was glamorous.

In Australia we also call the pavement the footpath

I think I’d reserve footpath for a path not associated with a road, such as going through a field.

Which reminds me of that other confusion for US travellers in the UK. Last summer I was walking through London and heard someone say “Where’s the subway?” Detecting an American accent, I decided to help. We were in a foot tunnel under the main road, called a subway in the UK. He was, of course, looking for an underground station.

The entrance to the tunnel was signed as subway, and as this was just off Hyde Park Corner, right in the middle of the tourist area between Buckingham Palace and Harrods, I imagine that confusions happens a lot.

In NZ, a gravel road was called a metal road.

I was travelling in Scotland at the weekend and a friend told me that in the area we were at the time, the roads used to be red. The local quarry produced a red stone that was used as the metal in the tarmac. The quarry is now exhausted but you could still see a red tinge to the road surface.

I mentioned this thread and tarmac versus asphalt and she recalled a farm she worked at as a vet where a road was being resurfaced. Most of the road was surfaced with tarmac but the bit that went through the farm they used asphalt. Apparently, the cows crossed the road twice a day and it is easier to clean an asphalt surface after a herd of cows has crossed than a tarmac surface. She reckoned asphalt is more likely to be used on motorways, but I’m not sure being a vet makes you an expert on road surfaces.

I’ve come across the phrase “drinks-do” for London happy hours.

The phrase “drugs party” immediately puts me in mind of this song:

I wonder if this relates in some way to “math” vs “maths”

I think probably Math and Maths is just one of those random things; and for Statistics, I believe Americans say Stats, with the Brits, rather than referring to Stat.

I think that’s not correct. My sense is that Americans say “Stat” (or at least they did when I was in college way back when). They also abbreviate “Economics” as “Econ.” Do Brits say “Econs”? On the other hand, there is in the U.S. a discipline that studies communication. The field was initially called Communication, but somehow along the years it has acquired an s and become Communications. It’s similar to the way college Admission departments have turned into Admissions.

Stat and Econ sound like abbreviations of college course titles. I was thinking more colloquially, ie that people are more like to refer to “baseball stats” than “baseball stat”. http://m.mlb.com/glossary/standard-stats

This reminds me of how the US uses Math, for what we call Maths!

The phrase ‘drinks party’ has been in use in the UK for at least the last 50 years. Also known as ‘a stand up and shout’.

US version is cocktail (NEVER cocktails) party.

I think “books” editor has the merit of distinguishing a person in charge of literary coverage in a newspaper from a person in charge of editing a specific book, though even then a “books” editor could mean an editor in charge of editing a whole list of books. And a “jobs” report about national employment issues is worth distinguishing from a “job” report, which to me sounds like the paperwork from someone who installed your boiler or fixed your aerospace engine.

To me, in New Zealand, a “covers band” is a band which plays cover versions of songs by a variety of groups – paradigmatically, in my going-to-hear-covers-bands years, such bands would always play a cover of “Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door”.

I wondered if a band that played covers of only one band’s music might be called a “cover band” – but then I recalled the posters for “The Pink Floyd Experience” I had walked past on my way home, and decided in that case that they were a “tribute band”. (Quite a good one, too.)

On the other hand, doesn’t AmE usually use ‘sports’ where BrE has singular?

Yes, that’s the one counter-example I am aware of. In the college/university world, U.S. has somewhat nonsensically gone from “Admission” (the people who decide who gets in) to “Admissions” and “Communication” (as an academic discipline) to “Communications.” A quick Google search suggests that U.K. has followed suit.